Aloe Blacc: “The trumpet only has three keys so I thought it would be the easiest out of all of them to play”

LA soul singer of ‘I Need A Dollar’, ‘The Man’ and ‘Wake Me Up’ fame, talks songwriting and social consciousness

Egbert Nathaniel Dawkins III, known as Aloe Blacc, is the Los Angeles-born singer, songwriter, actor, producer and musician, who shot to fame in 2011 with the hit single I Need A Dollar. His career started much earlier, creating music at high school with DJ Exile – with whom he would go on to form the hip-hop group Emanon – and putting out his first solo album Shine Through, but it was Truth & Soul-produced Good Things that spawned I Need A Dollar and took Aloe into the mainstream.

In 2013, Aloe Blacc co-wrote and performed vocals on Avicii’s Wake Me Up, which reached the Top 5 of Billboard’s Hot 100 and charted at No 1 in more than 20 countries. His third solo album and major label debut through Interscope Records, Lift Your Spirit followed shortly after, featuring production and co-songwriting from DJ Khalil, Pharrell Williams, Theron Feemster, Rock Mafia and even Elton John – for the sampling of Your Song‘s chorus on The Man, which went on to sell 2.5 million copies in the US and topped the UK Singles Chart. The album reached the Top 10 both sides of the Atlantic and received a nomination for the Grammy Award for Best R&B Album in 2015.

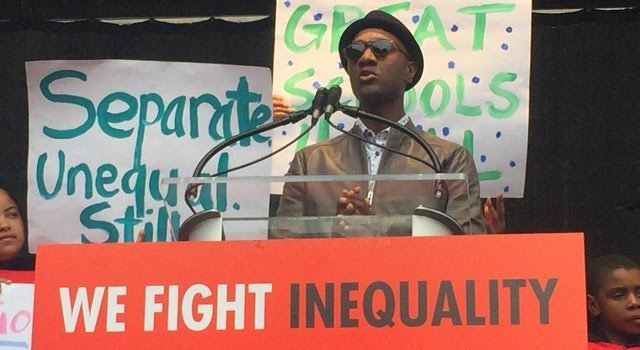

Last month, Aloe performed and spoke at the Stand For School Equality rally in New York, joining Jennifer Hudson, DJ Jazzy Jeff and organisers, Families for Excellent Schools, calling for change to the city’s ‘unbalanced education system’. We covered the news of the event and it was his involvement which prompted us to speak with Aloe about his schooling, songwriting and social awareness. We caught up with him back home in Los Angeles, working on his next solo album…

Thinking back to your earliest experiences of making music, what came first for you – writing lyrics, melodies, or playing an instrument?

“It was lyrics. I was young, probably nine years old, and I would write raps in this little notepad I had. I was listening to pop music at the time, so early LL Cool J and groups around that time, just trying to copy what they were doing because it sounded cool. Hip hop was something I fell into because the kids on the block were breakdancing and that was the music they were playing, so that’s what made hip hop interesting to me. Then I found the words even more interesting.”

You started playing the trumpet then, didn’t you?

“Yeah, around about the same time. In third grade, I joined the school orchestra and learned the trumpet and continued that until freshman year at high school.”

What made you jump from LL Cool J and hip hop to the trumpet?

“Well, it’s not so odd when you consider what I had access to. I think any kid, that has access to a lot of different influences, is capable of engaging. You don’t even think that it’s weird; you just do it because it’s available. I think I just wanted to get out of class! Going to the ‘school band hour’ kept me from being in the regular music class with the rest of the kids playing tambourines and stuff. It was something new, something interesting and challenging.”

So it could’ve been any instrument that you got into at that age?

“It could’ve been any instrument, except the trumpet only has three keys so I thought it would be the easiest out of all of them to play!”

When it comes to your music now, is lyric-writing a separate process for you or do you tend to freestyle and let the words flow naturally?

“Because I started when I was nine years old, before I had access to equipment, or a DJ or a producer, so it was just words – playing with concepts and rhymes, and figuring out patterns and cadence. That was the beginning. Then, around high school, when I started producing and making my own music, I was sampling from so many different genres, the concept of writing my own melodies came into play.

“Of course, having a monophonic instrument like a trumpet, I was able to take some of the influence from what I was learning to play in school was helpful as well. But I was sampling from soul and folk records. I fell in love with folk because of the seemingly simple, but profound, lyrics that were very inspiring.”

Were you a solitary child, just tinkering away on your own, or had you started making music with other kids?

“When I was a freshman in high school, I met a DJ named Exile who lived nearby and we started making music together. So that was when the collaborations started, otherwise I would’ve just been writing lyrics for myself, with myself, forever! But I found a good musical partner in Exile, so I would pair my lyrics with the instrumentation or beat he was making, and they often matched.”

Have you continued to look for that sort of musical partnership throughout your career?

“Nowadays I generally sit and write on my own. I only get with a producer at the end of the writing process, if I need it. So that’s how I like to engage now, but for the sake of the industry I entertain the record label and work with whoever they suggest, because I signed a contract and I’ll play by the rules for the business.

“But when it comes to writing songs, that’s something I like to do on my own. So when I get into the studio with a producer, I may be bringing in songs that I’ve already written and then share my melody and lyric with their production. Or I’ll allow the songwriting process to be generated from that studio session, because the music they have might inspire lyrics for me to write.”

So your songs might evolve, but you aim to have them finished before you even set foot in the studio?

“Yeah. I don’t know if there’s any way you can find a proper definition, but for me, a song is lyric and melody. You can add guitar or piano chords on top, but that can be many different ‘colours’ and progressions of chords. One thing that will never change is the lyric and melody, so for me that’s the song.

“In my experience, because I come from hip hop, we’re so used to remixing, it could be anything – I could write what I think is a country song, but put a dance beat to it and it becomes an EDM song, or I could put a reggae beat to it and it becomes a dancehall song. It’s sort of the dirty secret that a lot of fans of music don’t really recognise, but songwriters do. And it’s why a lot of songwriters get upset about too, because you get in the studio with a producer and they’re waiting for you to come up with the gold!”

Aloe: “I never censor myself when I’m writing. I write whatever I want, no matter what it sounds like…then curate later”

When you go into the studio, do you have a whole bunch of basic songs to choose from or do you demo everything first and get it down to the 10-15 that’ll become the album?

“For this album, there’s a lot so it’s just a matter of curating at this point. I never censor myself when I’m writing. I write whatever I want, no matter what it sounds like or what it feels like, then curate later. After 20 or 30 songs, I’ll decide what 10 belong together to make the statement I want to make. I’ve got a lot of songs that I really like, so I’m just in the process of deciding how I want the album to sound. I’m still just figuring that out, but I think my statement is made by the lyric and the melody, then you colour it, however you want to colour it, with the production.”

You broke through with your Good Things. With that record, did you have any idea that your career would take off?

“When I was working on Good Things, because I was an artist with a niche audience, I figured it would just remain that way. But when it changed was when I got word that HBO’s television show, How To Make It In America, wanted to license I Need A Dollar. Because of that, the song had visibility in a way that otherwise would’ve left the album relatively obscure.”

I Need A Dollar became a huge hit, especially here in Europe. Can you remember where you were when you started writing that song, and which part came to you first?

“Yeah, I was driving, I think. I’d been listening to John Lomax’s field recordings of the workers in the chain gangs and farms. They were singing their own tales of woe, through old blues songs – some ‘call and response’ and some solo – and I just started coming up with my own work songs. The way that I wrote it, and the way that it sounds, are two different things.

“I wrote it as a foot-stomping, hand-clapping, kind of church, gospel rhythm, but in the end, working with Truth & Soul [the production team of Jeff Dynamite and Leon Michels, who are credited as co-writers with Nick Movshon and Aloe Blacc] they offered this instrumental. At the end of our sessions together, I had this I Need A Dollar song dancing around in my head and I just thought I’d demo it to this funky, soul groove that they’d made, and it worked.”

Similarly, The Man was another big hit for you. What made you work with that Elton John line from Your Song and why did you keep it in?

“Well, it’s sort of the genesis of it. I’m a big fan of singer-songwriters, who I consider the best, like Nina Simone, Sam Cooke, James Taylor, Joni Mitchell, Carole King, Cat Stevens… I’d sampled the Elton John and made a hip hop beat out of it, and I thought I could sell the beat to a hip hop artist, or something. But then I brought it into the studio when I was working with DJ Khalil and I said, ‘When I was in little school I used to play a song called Russian Sailors Dance on trumpet…’ I think it was from a play called the The Red Poppy.

“I said, ‘Let’s adopt the melody from the Russian Sailors Dance and have a two-bar tag at the end, to make a six-bar cycle with the chorus.’ And I sang it to them, and Khalil’s musician Sam Barsh got on piano and made an interpretation and that became the instrumentation underneath. Your Song was the genesis of the chorus and as that was such an inspirational song, I wanted the lyrics to stay in that vein; self-motivating, pull yourself up by your boot-straps and recognising your flaws, but admitting them, and continuing on to be a strong and successful individual.”

Did the theme of The Man set the tone for the album?

“No, it was later in the production for the album. My A&R at Interscope, John Ehmann had listened to a lot of songs that I’d done and said, ‘I’d like you to work on bigger themes, bigger anthemic ideas’ and that was also part of the inspiration to go back in the studio and say something. Also, I had a chance to meet with Dr Dre – he invited me to a Lakers game and we sat in the private box seat – and we had a talk about music. He was just mentioning how there are no R&B artists that have the swag of Marvin Gaye, with the vulnerability, but still very respected by men and very loved by women.

“It’s not typical right now for artists to do that, and he was suggesting to me that it was possible, if I worked at it, I could figure out that lane to engage in. So I went back to the studio with that in mind and I think that’s when I decided I’d take The Man for myself, rather than try to sell it to a hip hop artist, and accomplish that directive offered by Dre. And I think it worked.”

Aloe Blacc at the Stand For School Equality rally in New York City in October 2015

Marvin Gaye was also well known for being involved in social justice, and you recently performed in support of Families for Excellent Schools in New York City. Was this a one-off or are you keen to be more politically active?

“I’ve been granted the opportunity to have access to everybody’s ears and, through their ears, their heart. So I feel like I have the responsibility to promote compassion. Like I say on my album, ‘love is the answer’ and if we all learn to love a little bit more, the world will be better for it. The only people who are able to promote love and compassion on a multimedia, global scale are the artists, filmmakers and musicians. Politicians seem to be failing and maybe people don’t want to listen to politicians. Maybe they’re disillusioned, but for some reason, they listen to us so we’ve got to be there to offer that voice.”

Does your involvement in these causes have a further influence on your music?

“The music I make that I don’t think is worthy of the ‘mission’ of magnifying compassion, I don’t release. I may make a stupid, funny song that makes me chuckle with my boys, but that’s not for everybody or mainstream consumption. When you’re hanging with your friends, having a drink and joking, we make songs like that, but it’s unfortunate that that’s what other people actually put out! It’s fun to have a song that’s comedy, like Weird Al Yankovic, but not when you’re subjugating and denigrating, and being misogynistic – that’s not what we really need in the mainstream. So I’m very pointed and particular about what I release.”

Related Articles