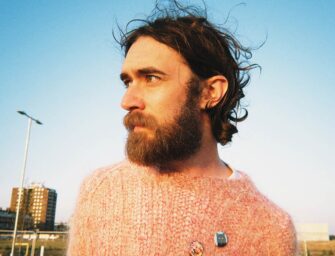

Hard-Fi’s Richard Archer: “Whether I like it or not, it’s become my identity.” Photo by Bernice King

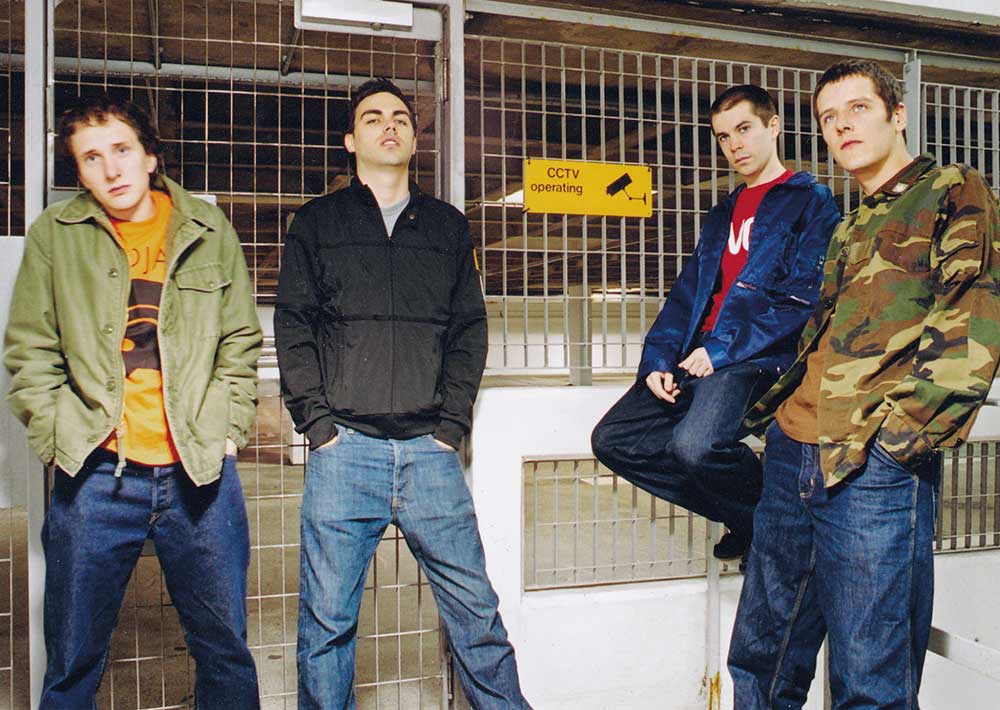

The Staines band’s frontman on the album that turned suburban boredom and a minicab office into a collection of anthems

Two decades on from its release, Stars of CCTV remains a potent snapshot of suburban disillusionment and ambition. Hard-Fi’s debut, forged in a disused minicab office in Staines and released in 2005, infused indie urgency with dub, punk, and dancefloor energy. Though singles like Hard To Beat, Living For The Machine, and Cash Machine are the band’s signature touchstone, the album as a whole remains just as sharp today – its themes still resonant, its sound sharp, and its spirit undimmed.

Now, to celebrate the 20th anniversary of their Mercury-nominated, triple-platinum debut album, Hard-Fi are giving it the deluxe reissue treatment, complete with live tracks and special remixes. In this interview, Archer revisits the DIY ethos and inspiration that launched his band’s career – and sparked something in anyone dreaming of escape from their dead-end job, even if only for the album’s duration…

Read how Hard-Fi wrote ‘Hard To Beat’ in our Summer 2022 issue

How long had you been writing songs before the ones that made up the album began to emerge.

“I’ve been writing songs since I was a kid. I’ve always been into that sort of thing; just doing stuff for myself, writing music for my GCSE music. I always looked up to my cousin. She was really cool, she was into Bowie and Prince, and had a synth and a guitar, and I was like, ‘I’d like to do that.’ My brother also played a bit of guitar, and I’d got into synths and thought I needed to learn to play the piano.

“My nan used to play the piano. I started having lessons but I always preferred making up my own songs to having to learn the ones that I was supposed to learn. I would invent little things. So, since forever, I would be writing songs, and that went on and on and on. I was in various different bands, doing different things.”

What happened next?

“Then I got this band together called Contempo, which was me and my brother [Steve Archer] and some friends of mine. We actually got signed to London Records by the guy who later on became the Hard-Fi manager [Warren Clarke]. He set up his own label to put the first Hard-Fi records out on.

“We made a record. We had Mick Jones of The Clash producing it, and Gary Langan out of Art of Noise engineering, amazing stuff. But I don’t think, as a band, we were ready. I remember suddenly everything slowed down. Whenever I did stuff by myself, it was quick and more fun. Suddenly, you’re in the studio and everything’s taken ages, and it doesn’t sound quite as good as I want it to.

“London Records got bought by someone bigger. Warren who signed us got made redundant. We got dropped and that was the end of that really. I fell out with my pals for a little while over that, but I’d still been writing. The idea was sort of like, I’d got into Northern soul, and it was sort of punk meets Northern soul. It was a bit Dexys, even though I didn’t really know that much about them then. I only knew Come On Eileen at that point. I didn’t know the first album, which is terrific.”

Did that then lead to Hard-Fi?

“Some of those songs I’d written towards the end of that went on to become Hard-Fi songs. Living For The Weekend, Unnecessary Trouble… they were songs that we had played as Contempo. We didn’t record them, but we played them. And then there was ones in between, so Better Do Better and it was probably Cash Machine, Hard To Beat, Move On Now, Stars Of CCTV, Tied Up Too Tight – were ones were it was like, ‘Ah, okay…’

“There were still elements… I love rock music. I love The Stones and The Doors, I was a big Nirvana fan. When Oasis came along, I got my hair cut, I loved it. But I’ve always really loved dance music and soul, so I wanted to try and have elements of that in there. It kind of evolved out of what Contempo was into Hard-Fi.

“Contempo could occasionally sound a bit retro, we had a brass section, which weirdly became quite hip when you had people like Mark Ronson doing all that sort of stuff. But at the time it was all French house, so we were completely un-hip.”

You must have believed in yourselves and the songs enough to go for it again after it went wrong with Contempo?

“When I was sat there, I could never imagine someone saying, ‘Yes, okay, we’ll do this.’ But I always had this weird optimism that it would work out somehow and it would come good. I guess as well, with having Warren Clarke, who set up Necessary Records, he had discovered us and now he had been made redundant. He was trying to find his own way and figure out what he wanted to do and he set up this label.

“He was still there, going, ‘I like what you do,’ and he’d heard some of the new songs. So, we had that person there. At the same time, I also bumped into a guy from round our way in Staines called Wolsey White. He was a bit of a face around our way because he had been in a few bands. He was in Supermodel, lots of little things that were always on the edge of doing stuff.

“He heard it and was like, ‘I really like this, can I mix a couple of the tunes?’ And that was when he got involved as well. Having a couple of people saying, ‘This is really good’ was crucial, even though it felt at the time that there was a little bit of a feeling that you’d had your chance and you blew it, so that’s that.

“We always talk about how the album was DIY, and how we made it ourselves in a cab office, and we did. A lot of the main reason for that was money, but it was also that feeling of having been on a major label, gone into the studio, had an amazing time… We learned so much from Mick and Gary. But it just felt like, ‘We can do this ourselves.’ The technology was available to do it and that was a big reason for doing it ourselves. We don’t need everything slowed down, or a million opinions, let’s just get on and make it, and if it doesn’t work, we’ll try again.”

Hard-Fi’s Richard Archer: “I was just having fun. Once you do that, good stuff comes.” Photo by Bernice King

Did your writing process evolve between the early batch that you carried over and the new ones you were working on?

“It definitely evolved. I think some of that was the technology changing. When I was writing stuff in Contempo, we didn’t have a laptop or anything like that. I had a Roland VS1680. It was a real pain in the ass to edit on that. Whereas, once you got the computer… For instance, Cash Machine – I got this bassline that sounded really cool, and put a beat to it, and then it was like, ‘Well, where can this go?’ And it grew from that. I wouldn’t have been able to do that so easily on the other thing.

“I still would generally sit and write with a guitar. At the time I had an electric guitar, an Epiphone Sheraton. I’d sit with that, not plugged in, quietly sitting there, and then work stuff out and start putting it all together. A riff and bassline first, then words that seemed to fit with that, and then expand on the words to go, ‘Okay, what’s this about?’ Then get into editing the words a bit more, but always, generally, starting with the riff, and then a melody, then the words.”

That’s interesting because the melody inspires the first line couple of lines and then you yourself are trying to work out what you’ve written about and expand upon that…

“Sometimes, for instance Better Do Better… that’s a very obvious story about splitting up with someone, and then them coming back and that whole dynamic – wanting to get back together, but you know that it’s just because whatever they left you for hasn’t worked out. At that time, that hadn’t happened to me, but the words came out and it was, ‘Oh, this sounds like an interesting story and I can get how you could feel like this.’ Then it did happen to me, and I was like, ‘Oh, that’s kind of interesting,’ because it’s almost like I’d predicted the future. But yeah, they would just come like that.”

You mentioned doing music at GCSE, were you also someone who was also into language, reading and writing stories?

“I’ve always loved reading. But then when I went and did A levels, I was daft and I didn’t do anything like that. I didn’t do anything that I really liked and I failed them miserably.

“When I listen to songs, I go for those that either say something that you yourself feel, like they’ve completely looked inside you and get what you’re feeling, or they take you somewhere/make you imagine you’re somewhere else, not sat in Staines, and it’s really boring, and I’m broke, and I’ve got nothing. “When we used to go into the studio, we’d put on a Robert Johnson CD. I would imagine I was sat on a veranda outside a wood-built house down in the Deep South, and it’d be raining, but really hot. I’d never been there, didn’t know what it was like, but that was what I felt and it was inspiring. Get in there and feel like you’re somewhere, and then ‘Right, come on!’”

Were there any key moments in the studio where you realised it felt different to Contempo in terms of how strong the songs were and thinking maybe it would happen?

“I think when we met Wolsey White. I’d demoed most of the songs and they were pretty good, but he came in and it was sort of the same time that we’d got this space. We originally got it to rehearse in, because it was cheaper. The nearest rehearsals rooms to us were in Park Royal in Acton, a ball-ache to get there and back in rush hour when everyone’s finished work. It was cheaper to have the space. We started recording there, because I’ve always been into that side of things.

“It was a little room, a filthy old cab office, nicotine over the walls. When you opened the door out into the main corridor, there was a concrete staircase and we’d put a mic out there and it would sound really big. We thought we were Led Zeppelin. That was really exciting, getting in there and starting to record. Rather than it being my drum samples and loops and stuff, really getting the band on there. Then Wolsey coming in and doing what he did… He would take it a lot further in terms of saturation, distortion, that kind of stuff. Suddenly it started to sound like a record.”

And that was the turning point?

“At that time, we had got some things together, and we were taking them out to people, and it was still like, ‘Well, yeah, but you’re not what’s happening right now. You’re not art rock,’ or whatever it was. No one really wanted to know.

“It was only when, through a sort of convoluted route, labels in the States had heard it. We got this story, which obviously was a big deal for us, and still is… Rick Rubin was like, ‘This is one of the best things I’ve heard all year.’ They were then getting back to their UK representatives, ‘Are you on Hard-Fi?’ And they were like, ‘Nah, it just sounds a bit like The Clash and The Specials,’ and they were like, ‘Yeah, exactly.”

You didn’t see yourselves as part of that whole “new rock revolution” scene?

“We always felt outside of that. But we were incredibly lucky to be at the same time as that wave of new British bands, because it’s much easier when everyone wants to hear about what’s going on and what’s new.

“I think it was probably us, it wasn’t to do with anyone else. It was just that it all felt a bit middle class, and we felt like we were oiks. It wasn’t that at all, really, but sometimes it felt that way a bit. The press, they almost didn’t quite trust us, and we were like, ‘We’ve been making this album on a shoestring, without a pot to piss in. This is as real as it gets.’”

Hard-Fi’s Richard Archer: “Whatever I felt like writing about, I’d write about.” Photo: Mark Thompson

Then it all happened and, the singles and album did amazingly well. As the person who wrote the songs, did you have a different sense of pride?

“Yeah, I think so. It’s kind of strange, because they just sort of happened. It was just what I did at the time, that would be my thing. I’d come in and I’d sit down, I’d listen to some tunes, and maybe I’d go, ‘That’s pretty cool.’ I’d sort of nick it and try and turn into something else. I just did it, and it just sort of came about.

“Whatever I felt like writing about, I’d write about. It gets to the point where people ask, ‘How do you write songs?’ And, ‘You need to write a second album, how are you going to go about that?’ I don’t know, it just happened. I probably could sit down and go, ‘Okay, well, what did I do here?’ But, and it’s something that I’ve only really realised a lot later on, I was just having fun. Once you do that, good stuff comes. If you sit there and go, ‘Right, I’ve got to knock out something amazing today,’ everything clams up and it becomes really hard, or you overthink everything.”

That must be why it’s so hard to replicate – because you can never get back to those conditions where you’re young, with your mates, doing it for fun without label pressure…

“I did have… One of the things that was great about Warren at that time was that I would say, ‘I’ve got this tune,’ and he would say, ‘Oh, that’s great, but the chorus ain’t really doing it.’ I’d go away and write a new chorus. I had that little bit of to and fro to say, ‘You can do better than that.’ I’d go away, and then he’d say the same thing. By about the third chorus, I’d start to get a bit pissed off, and then I’d be like, ‘Right…’

“Hard To Beat for instance, had several versions. The verse, guitar riff, bassline, lyrics, were pretty much there from the beginning. The chorus had several iterations. I’d written most of it on the guitar, it was only when I went to try something on the piano, and obviously I would play that differently to how I play the guitar, and come up with different chords. It’s got that sliding seventh in the chorus. It was like, ‘That sounds pretty cool.’ It sounded a bit like Daft Punk, and I was really into that. So, there was an element of finessing going on.”

Was that through experimentation and trial and error, or being well versed in musical theory, and trying specific chord sequences?

“I actually studied music at university. I went to Kingston University and the main thing I did there was music and technology. Most of it was sound recording and the technology side of stuff. I knew enough but I didn’t go, ‘I know what will work here, a minor seventh on the fourth.’ I would just sit and play and something would come along and I’d go, ‘That’s interesting, what’s that?’ And then have enough to work out where it should fit in.

“When I think back to those times, before we had a major label and everything took off… In our little studio, we’d be there all night, trying stuff out, going to Portobello Road looking for clothes, coming up with an idea for a video and making it for a couple hundred quid. Those are probably the fondest memories I have. It was good fun, it was exciting, and we felt a bit like we were sticking two fingers up to the system because we were doing it ourselves.”

How did you feel about the songs now, are there any that you’re particularly proud of?

“I went back and listened to the album. We’d been playing it live still, but I hadn’t actually sat and listened to it. I was genuinely kind of like, ‘Wow, this is really good and better than I remember.’ It’s hard to say which songs though.

“Something like Hard To Beat changed our lives. The thing with Hard To Beat is… I’m a season ticket holder at Brentford, and they often play it there, and I’ll always be there going ‘The snare’s too loud.’ But I think probably Hard To Beat, just because the way the chorus does change, and it grows and it builds and it keeps your attention. I like the bassline and I like the guitar riff.

“I hope it captures that feeling of when you see someone, they take your breath away, and then they’re interested in you. It’s like, ‘Oh my God, what do I do now?’ When you’re young, that excitement and that feeling of going out with your friends, and what might happen.”

But it wasn’t a one-single album, there’s lots of other big songs on there like Cash Machine and Living For The Weekend…

“Better Do Better also came out, I think it was the last single. Live, it always goes down really well. It’s interesting, when we came back and started playing again for the first time in 10 years, or whatever it was, we played The Forum in London and we did a little warm-up in a pub in Milton Keynes, The Craufurd Arms. Great venue, about 500 cap. We were playing the set, and it was really interesting how the first album songs just seemed to suit that room.

“There’s a book by David Byrne [How Music Works] where he talks about how music evolved to almost fit the way it’s been listened to. For example, punk worked in small rooms. We’d then do some tracks from the second album where we’d got a string section and they felt a little bit overblown. The first album ones just felt right.

“When we went to the bigger stage, the second album ones felt great, but in there, it was almost like that feeling we had when we first went out and did them, supporting someone doing your best seven songs: bang, bang, bang, bang, bang, bang, bang, and off.”

Can Hi Fi fans expect any other treats this year?

“We thought we’d take the album out, but I’ve also written a new album. We want to celebrate this, because it was a big moment, but also, we don’t want to keep playing only old songs. We would like to be able to go, ‘Hey, we’ve got some new stuff coming.’ We’re going to put that out, and we’re just waiting to see when that will be, timing-wise. We’ll get that out there, and then get back out and see what people think of those. But we always finish with Living For The Weekend.

“We are doing a couple of shows at Pryzm where we’re going to do the whole album. That’s interesting because we haven’t played Unnecessary Trouble for probably 15 years. We dusted it off, and it was ‘This one’s great, why haven’t we been playing this?’ That was part of the problem before, because we can’t just play the whole album all the time. But we all like all the songs, so we’re going to dust those off and get them out.”

To sum it all up, what does stars of Stars Of CCTV mean to you at this point in your life?

“Whether I like it or not, it’s become my identity. What it means to me is, it was a really exciting time in my life. It changed my life. There were difficult times as well, but I got to go travel the world, play gigs, and it was really incredible.”

Related Articles