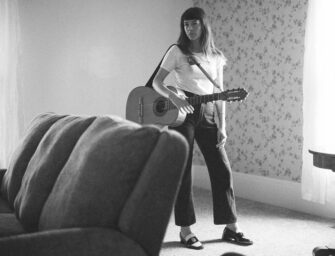

Ada Lea: “Simply put, a creative work is the result of a series of small decisions.” Photo: Tess Roby

The Montreal songwriter offers a personal guide to songwriting: from notebooks and deadlines to the power of trying things live

Ada Lea has never approached songwriting as a fixed formula. The Montreal artist, also known as Alexandra Levy, has steadily built a body of work that melds together music, painting, and poetry. Her sound is intimate yet expansive, marked by shifting structures, textural arrangements, and a lyrical voice that balances emotional clarity with surreal imagery.

Lea’s new album, When I Paint My Masterpiece, arrives 8 August via Saddle Creek and reflects a period of personal and creative transformation. Written in the wake of loss, change, and renewed artistic focus, the record finds Levy embracing slowness, intuition, and the messiness of process.

In this piece, she shares five lessons learned through songwriting – ideas that continue to shape how she works, listens, and lives…

1. KEEP EVERYTHING

It’s happened countless times now that a song (or especially a fragment of one) ends up making a huge comeback somewhere down the line.

2. KEEP A NOTEBOOK WITH YOU

Write everything down. Passages you read, conversations you overhear, signs you see, dreams you remember. Don’t assume you will remember anything later—you will most likely not remember anything later and you will be very happy to have written it down somewhere.

3. DOCUMENT THE DETAILS

I think I learned this from Jeff Tweedy’s book How To Write One Song, but I’d recommend keeping a record of the lyrics and chords to all your song ideas. Details about the key, capo or guitar tuning.

Ada Lea: “There’s a myth which is that creative freedom means access to endless financial resources, ample time, etc. The opposite has been true for me.”

4. SET CONSTRAINTS

Deadlines. Prompts. Creative Boundaries. Limits. Simply put, a creative work is the result of a series of small decisions. Added up, they create a song, or a painting, or a piece of writing. Most decisions are intuitive, based on the gut instinct – but still, at a certain point, you will need to make a decision and then move on to the next decision. My feeling is that “creative blocks” come from not being able to make decisions.

There’s a myth which is that creative freedom means access to endless financial resources, ample time, etc. The opposite has been true for me. The stakes shouldn’t be too high, though. Examples: 1) book a weekly set at a café and make a plan for yourself to always add one new song to the rotation. 2) Set a recording date. 3) Book a small show before you feel absolutely ready. 4) Do the “songwriting method” where you write a song every three days for one month four times per year.

5. TRY NEW MATERIAL OUT LIVE

Record yourself. Listen back. Adjust. George Saunders in A Swim In A Pond In The Rain: In Which Four Russians Give a Master Class On Writing, Reading, And Life talks about his editing phase. As he’s reading along to his work, he imagines this needle moving from one side to the other:

“My method is: I imagine a meter mounted in my forehead, with “P” on this side (“Positive”) and “N” on this side (“Negative”). I try to read what I’ve written uninflectedly, the way a first-time reader might (“without hope and without despair”). Where’s the needle? Accept the result without whining. Then edit, so as to move the needle into the “P” zone. Enact a repetitive, obsessive, iterative application of preference: watch the needle, adjust the prose, watch the needle, adjust the prose (rinse, lather, repeat), through (sometimes) hundreds of drafts. Like a cruise ship slowly turning, the story will start to alter course via those thousands of incremental adjustments.”

So, for songwriting, this might look like recording yourself playing the song live, noticing where your attention wanes, making note of it, going back, making edits, recording again, going for a walk, making more edits, etc.

Related Articles