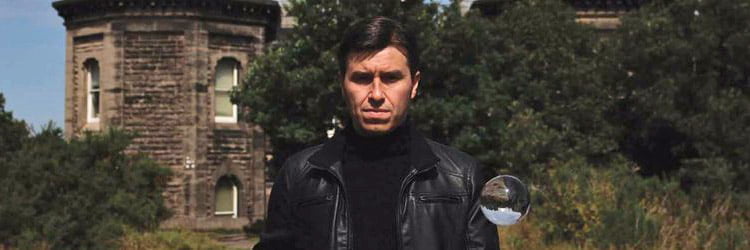

Nick Ellis: “I find my best work comes through when recording in a room with a special ambience”

This Liverpool-based songwriter discusses how the unique location his debut album was recorded in profoundly influenced the haunting final outcome

Nick Ellis – previously a member of indie band The Maybes? – is a Liverpool-based writer who combines his classic songcraft, eye for a story and accomplished guitar playing, in order to create a sound all of his own. His debut, Daylight Ghosts, was recorded in Liverpool’s St. George’s Hall Crown Court Room, the very place where the last British man was sent to the gallows from in August 1964. Though released last November, it’s a record that is worth revisiting, slowly seeping into your soul and rewarding repeat listens. With that in mind, we decided to have a quick chat with Nick about the unique recording space and his developing style…

You mention influences such as Gil Scott-Heron, Townes Van Zandt and Ken Loach – are there specific ways in which these people have helped to shape your sound?

“Gil Scott influenced me to think about metre and delivery and how a story can take place over a number of scenes. The key to Gil’s music is the groove, which in turn, allows the story to have a pace, mood and a kind of ‘street map’ where incidents take place and the characters that frequent them go about their daily lives.

“Townes, basically taught me that it’s ok to write about heartbreak using simple everyday language and how powerful that can be. No one writes a heartbreaker quite like Townes does. His poetry is simple, humane and romantic.”

How about Ken Loach?

“Ken Loach opened up the possibilities for me to look at the characters in my writing as being allowed to appear flawed, emotionally unstable or occupying that uncomfortable realm of daily life where loneliness and mental health frequent. Ken Loach isn’t afraid to put his characters in uncomfortable situations and watch their natural reactions come to the fore – a master of letting his characters become the story itself.

“So, yes, eventually, these influences did shape my sound, but, they were rooted in other artists which led me to them. In the case of Gil, it was Bill Withers. With Townes, it was Dylan. Ken Loach came via John Osborne.”

Similarly, how did recording at St George’s Hall Crown Court Room alter the sound of the record?

“The record ended up being a very unique document because of it. I’d say recording at St. George’s Hall Crown Court Room dictated the overall concept and narrative of the album and I’m pretty sure the recording engineer, John King and the mix engineer, Danny Woodward, would agree. It wasn’t just the sound of the room that influenced the record, but the approach. All the different elements combined gave us this very special essence captured in a moment in time.

“We went in with a simple concept, to record good live performances of the songs in a great sounding room. A very old school approach, much like that of the early Davey Graham, Bert Jansch, John Renbourn albums, similar to the Topic Records era. We had a small window of time to record the whole thing; 20 songs in about six or seven hours. This gave the performances a very organic nature, combined with a direct immediacy reserved for old-fashioned storytelling: a man in a room with a guitar telling a story. The atmosphere of the finished recordings brought a height, width and depth to the songs that was never there before.”

Can that be heard on the specific tracks?

“For example on Walk Through The City, the marble, wood and stone brought out all these harmonic mysteries and gave the song a powerful, timeless quality. Almost ethereal. Overall, we had these unique sounding ‘short stories’ that took on their own characteristics and seemed to resolve into a natural order. A combination of time, place, the people involved and the performance itself gave us the record as it now stands. For all that recording studios are worth, a great sounding room should never be underestimated. I find my best work comes through when recording in a room with a special ambience. I need to feel that history transcending through the song, the essence of these rooms being ‘lived in’, their ghosts walking through the soundscape.

‘Daylight Ghosts’ album cover

“After recording Daylight Ghosts and its preliminary EP Grace & Danger, I now know that songs transcend the everyday, the now. They can be timeless pieces of moving history. Songs are an unexplainable mystery that I will one day hopefully be able to unravel. But, so far, there is still lots to learn. Compared to the likes of Kris Kristofferson or Tom Paxton, I’m a novice.”

How did your guitar sound develop?

“I’ve been playing and producing for years, but let’s stick to the acoustic side of things. My guitar sound, at present, developed over the last seven years through a number of changes. Back in 2011, I saved up and took some time out from working and spent the summer busking around Europe, learning to play to people. At first, I was using a classical guitar which had been handmade in Madrid, but was too quiet. I swapped it for this Dreadnought-type steel string in Stockholm, Sweden and I’ve been using it ever since. It had the right power and weight in the low-end to be heard in any busy city street. So, it proved itself. Eventually, I strung it using 13’s to give it an even louder presence.

“When I got back, I started doing gigs in clubs and cafes with the guitar and found that I was a bit limited when playing the fingerpicking stuff, so I experimented with all kinds of pedals. John Martyn has been a big influence, especially the Inside Out and One World era, so I took a nod from that and added delay to give me a bit of percussion and timing to go with my rhythm. It took time to get it right but eventually I feel I came out with a technique that is my own. I also like to drive my acoustic through a nice hot pre-amp to give the guitar a bit of life – a bit of Keith Richards. I find acoustics generally sound thin and annoying when put through a P.A.”

And that led on to fingerpicking?

“My fingerpicking technique, which is still in its infancy, was influenced by a few different players – Nick Drake, Davey Graham, Bert Jansch, Nick and Roy Harper, Michael Chapman, Leo Kottke, Robbie Basho, Peter Lang and John Fahey. A friend of mine, Dave Owen, who is a great player himself, was also instrumental in teaching me the key principles of fingerpicking. Most notably, ‘always keep your thumb busy.’

“It took a few years to find the right feel and patterns for certain songs. The arrangements often change with time, unconsciously. I mean, when I listen to Daylight Ghosts, I think ‘wow, I don’t play that like that anymore’. For instance, I now tune my guitar a semi-tone lower to E flat/D sharp standard to gauge a better resonance in my singing.”

Lastly, do you consciously collect the true stories that form your songs or is it a more organic process?

“I’d say the stories and characters have a way of finding, or wandering, themselves into a particular song. All these stories are true, all these characters are real, but they can only occupy a certain place where they are comfortable. When that place comes to life, the song starts to take shape. Some take time to develop, years in some cases. Others, do materialize more organically. Like Dance Of The Cat – it just came out. So, as far as I’m concerned, it already existed in the ether, in that place between dream and thought, in the subconscious or the invisible. Songs are like ex-lovers, you should never have too many. There are lots of good songwriters with lots of songs, but there are only a few songwriters with timeless songs. Like Jackson C. Frank, for example. Now, that cat transcends time.”

Interview: Duncan Haskell

Daylight Ghosts is out now. To keep up with Nick, follow him on Twitter at: @nickellis_music

Related Articles