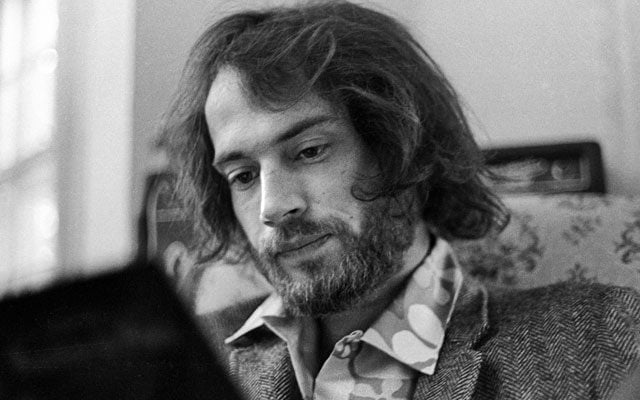

Chris Gantry: “The special thing about ‘The House of Cash’ was John and June, period.” Photo: Nancy Rhoda

Recorded in 1973 at Johnny Cash’s studio, we learn all about a lost classic from the country artist behind it

Chris Gantry is a country musician who has always been slightly outside of country music. His sonic trips combine elements of the outlaw scene, folk and pop with the determined vision of the Beat Generation. Early albums such as his 1967 debut Introspection and the follow-up Motor Mouth, show a unique artist who is starting to blossom – already a far cry from the sounds of Nashville at the time, they’re a universe away from today’s shiny offerings. Perhaps that’s why a potential boundary-pushing third release, recorded in 1973, never saw the light of day. Unable to find backer, Gantry shelved the album and carried on with his career. Until now…

At The House Of Cash has the feel of a lost classic which can now be discovered by listeners old and new. The album’s surreal songs were inspired by a peyote-fuelled quest to Mexico that Gantry had taken in 1972. Already a close acquaintance and disciple of Johnny Cash, he then bunkered down at the ‘Man in Black’s studio to record an album of psychedelic country which stretched the genre to its very limits. We’ll never know how much these tunes might have shaken up Music Row back in the seventies; instead we should just be grateful that they are finally seeing the light of day.

It’s a tale of drugs, friendship and high art which can only be told by Gantry himself. Which is exactly why we caught up with him ahead of the album’s November release…

It sounds like your trip to Mexico was extremely fertile for songwriting, what can you tell us about that journey?

“The journey was already seeded, planted, fertilised, and watered before I ever crossed into Mexico. You must understand, I don’t have a country music bone in my body even though my true songwriting apprenticeship was served around the country greats. I specifically went to Nashville because I was fascinated with the lyrics to early country music; stories of debauchery, devils, old women with guns and errant drunk farm boys who ran amok in big cities, run away small town girls who fell on hard times with vicious pimps and derelict boyfriends. True life depictions so missing in todays watered down country music or whatever the hell it’s called. I had come to Nashville fully equipped with inspiration from the beat poets: Kerouac, Ginsberg, Corso, Garcia Lorca, Lord Buckley, Lenny Bruce, Guthrie, Dylan, Baez, Richie Havens, not to say a full indoctrination of 50s doo-wop like Elvis, Jerry Lee, Cash, Gene Vincent. I brought with me from Queens, New York, the seed of outlaw-ism to Nashville that would infect change at a time when the whole world was exploding with revolution in the early 60s.

“By 1972 I’d had it with trying to write the perfect country song. I already had a lot of songs recorded by other artists including the blockbuster Dreams Of The Everyday Housewife by Glen Campbell. I went to Woodstock in ’69 and stayed with Tim Hardin whose songs I loved. We flew into the Woodstock Festival in a helicopter. Unbeknownst to Tim, I got up on stage with him when he sang Bobby Darin’s song, Simple Song Of Freedom. When I came back to Nashville my mind was exploding with musical possibilities. I started writing unleashed non-Nashville songs in a very radical way which, to be honest, suits my personality to this day. I love abstract subliminal realities that are charged with colour, mysticism, and humour in a Salvador-Dali-tipped-up-on-its-end-style. That next year Johnny Cash recorded my song, Allegheny, which I also performed as a solo piece on his TV show. By the time I got on the bus to go to Mexico, I was already seething with desire and intent to leap out of the box and wave my freak flag high.”

Can you tell us a little more about how you ended up at ‘The House of Cash’?

“I had gotten busted for growing pot on my farm in the 60s, which back then was like being a murderer. It was publicised as a federal crime. Even my lawyer Jack Norman Jr., son of a famous old-time Southern barrister, told me that if I served some time it would help further my career as it had for Merle Haggard, Johnny Paycheck, David Allan Coe, and a few others. ‘No dice,’ I said. After serving four long years in a military academy in high school, incarceration was not appealing in the least. It cost me but I got out.

“In the meantime, Johnny Cash called me and suggested I come stay at his house on the lake until things blew over, which I did. That was the beginning of my personal relationship with John. I had gotten to know the Carter family years before when I’d sneak into the Grand Ole Opry on Saturday nights. I’d hang out back stage gobbling up all the great jam sessions between everybody warming up in the dressing rooms. I had sort of a sneaker for Anita Carter; to me she was gorgeous with this undefiled pure voice.

“Moving into John’s was the beginning of endless talks about life, music, songwriting, beliefs and ideologies and, of course, the music business and also getting to know an idol of mine since I was twelve. Soon after, John asked me if I wanted to write for his company and make a record. I jumped at the opportunity. Shel Silverstein, who was my good friend and running buddy, Kris Kristofferson, my other running buddy, were frequently at the lake house hanging out, playing music, having dinner and just being crazy boys. The special thing about ‘The House of Cash’ was John and June, period. They were the glue that bound and perpetuated true art into the music business, besides being the nicest most generous people one could ever imagine.”

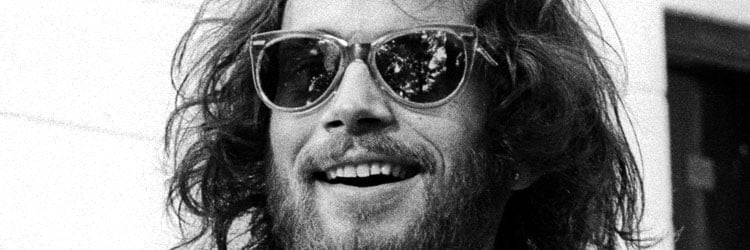

Chris: “John would breeze through the room while I was recording, give a word of encouragement and disappear.” Photo: Nancy Rhoda

Had your previous decade in Nashville helped you grow as a writer and artist?

“You can’t even begin to imagine what it was like to be a young songwriter being thrown into a pack of writers like Billy Swan, Linda Hargrove, Donnie Fritts, Eddie Rabbit, Kris Kristofferson, Mickey Newbury, Vince Mathews, Tony Joe White, Shel Silverstein, Lee Clayton, Bucky Wilkin, Mack Vickery, Tom T. Hall, John Hartford, Spooner Oldham, John Hurley, Ronnie Wilkins, Tom Ghent and Lana Chapel. Being around these young, deadly serious, super-excited and in-love-with-the-process songwriters was like being in the throne room of God listening to all the high energy lingo pouring out of the mouths of angels, seraphim, and archangels; it was pure Shakespeare 101.

“When I arrived in Nashville as far as the music biz went, there was nobody here who was my age except Billy Swan who had migrated from Memphis. We were It. Unbeknownst to the old Opry stars, there was a burgeoning counterculture revolution going on with the likes of Steve Davis [Take Time To Know Her by Percy Sledge], Jerry Smith who produced the House of Cash album, Brett De Palma, who today is a famous artist, and others. It was all going on, but it was me who brought the counterculture into the old archaic Nashville music business, infiltrating counterculture ideas that I had brought from NYC into my songs that were beginning to be recorded by country artists.

“About a year later, all the others who changed country music with their songs drifted in from the four directions and Nashville exploded. We met on the streets like the artists of the 1920s did in Paris, exchanging ideas and playing each other our new songs. It was a spiritual Renaissance experience and I was smack in the middle of it, hardly ever sleeping, burning, burning, burning, like all of us did. That bunch went on to write American classics, standards we still hear today.”

How much of an influence did the guys who played on the album have in the shaping of the final versions?

“The musicians who played on At The House Of Cash were so enthralled to be involved in something other than the non-stop country sessions they played day and night, year in and out, that they treated the experience as something they could also express themselves in musically that they never got much of a chance to do on your standard Porter Wagoner or Jim Reeves records. I would say they had a blast and made it a learning experience. I take my hat off to those players who really outdid themselves.”

How present were Johnny and June during the sessions, was their approval important to you?

“John and June were like godfather and godmother figures to many of us back then. They were to Kristofferson, Vince Mathews, Larry Lee, Shel Silverstein, myself and others. They never swarmed any of us but rather let us find our paths without imposing themselves on the art we were making, unless they decided to record some of our songs – which they did. John would breeze through the room while I was recording, give a word of encouragement and disappear. Making art back then was paramount to all of us, we treated what we did as High Art, trying to create things that would outlast us, using our God-given gifts in the most extraordinary ways that we could.”

Johnny also signed you to his publishing company, did you write many songs for other people or was it just your own catalogue that he was interested in?

“John didn’t care, as other publishers did, about getting songs recorded by anyone and everybody for the sole purpose of building up a valuable catalogue that made money. John was not in the money-making business. He was himself a high artist and benefactor to those like myself who he saw as a glimmer to the same things he himself aspired to do and be. Publishing mattered little to him, only the great works that were produced around him gave him satisfaction and delight. The only music he cared about were works of art. He didn’t care if they turned a buck or not.”

From peyote to marijuana, what role did drugs play throughout the record’s journey? Have they aided your creativity over the years?

“Except for a couple of songs which were the product of a peyote experience in Mexico – Away Away, The Lizard and Different, my Peyote mantras – I never was able to write well on any kind of a drug, especially pot. To this day I am very straight-laced when it comes to my work. I will only imbibe recreationally, as in a drink or a toke, when I don’t have anything to do. I saw so many great artists bite it and go to rack and ruin from excessive drugs. My three best friends in the world died from overdosing. My work is too important to me to give up to the temptations of being high. I never recommended it to anybody.”

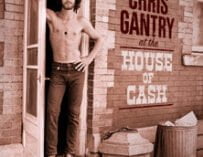

Gantry: “Nashville should be a little more accepting of this music than it was in ‘73…” Photo: Nancy Rhoda

What else can you remember about writing the album? How did the songs tend to come together?

“First, there is no way how to tell or to show another person how to write a song. How does one describe a Godly gift other than by showing them the result of that gift, which is ‘the song’. People ask, ‘Chris, how did you write that?’ I say, ‘well, I don’t know.’ An unction falls over me fuelled by desire to create something, combine it with intent and just get out of the way and let whatever is coming just roll through you. Let it fall onto the pad and just be the messenger, the deliveryman, the UPS guy, the mailman of the spirit. That’s really all I’ve ever been in actuality, I’ve never written anything in my life, I’m just a conduit for the muse, creative spirit, whatever you want to call it.

“When this collection of songs happened it was like a massive impulsive feeling I couldn’t describe. Some outworld phenomena that was taking place and raging inside me, it was as if I was vomiting art with an intangible seething melodiousness pouring through me like I was in a trance. Truthfully. There are seven more songs in this collection that I recorded that are still unfound. There were about eighteen in all, and some of those were the better songs. Where they are I couldn’t tell you. Maybe they will turn up someday like these did. One of them was about being in a hologram with God as he held my hand as we walked as he told me unknown and unheard of things, the song was called Shakedown On Macedonia Street. The one thing that happened in that encounter was that I was given the words to Tear. That, in its utter simplicity, is probably the most profound scripture that’s ever been given to me, for in it is the meaning of existence. I never changed or altered the piece as it was given to me, other than one word. Tear is the total eclipse of reason. To me, it is my small bout with perfection.”

At the time, were you aware how ‘out there’ the record was?

“In my book, Gypsy Dreamers In the Ally, which Kris Kristofferson said, ‘Is the best book about songwriting he’s ever read,’ I speak a lot about stalking the muse, always pushing forward quietly and stealthily through the doldrums and dark woods of the soul until the creative spirit see’s your diligence and drops a pearl of wonder in your lap. In retrospect, the recordings never registered in my spirit as being ‘out there’ but rather just another day of songwriting in the life of a New York hillbilly!”

Did you consider yourself to be an outsider?

“I have never considered myself to be an outsider. On the contrary, I consider myself the ultimate insider in that myself and a few other Nashville artists approached songwriting for the right reasons which is, love of the process, thus superseding fame, glory, money, and false self-importance. I think my perspective is less than unique but rather normal in its approach in that I give total credit for everything that comes through me to God who bestowed the gift on me in the first place, rather than being puffed-up in the illusion that I had anything at all to do with it.

“What aids my writing all these years is staying true to myself and not trying to be who I’m not, or as a wise person once said, ‘It’s better to be a fist class version of yourself rather than a second class version of someone else.’ Songwriting is a mystical experience, either you’re a tunesmith who pounds out songs like horseshoes on an anvil, or you deliver sacred messages as a servant with humility and joy.”

Looking back, do you now understand why it was hard to find a backer for the album, is there any lasting resentment?

“Backers are always present. In the face of destiny, nothing is ever too early or too late, Beauty is always right on time, whether it’s 45 minutes from now or 45 years later, like this record. Drag City is backing this work, they are my backers. Everything is on God’s time. As far as being resentful, the only thing that might make me a little resentful is Kroger not putting out the right cat food I need for the cats I feed, thats it!”

Why do you think it’s now a fitting time to release the record? Has Nashville changed and become more accepting?

“I couldn’t tell you why now is or isn’t a fitting time to release this record except that ‘hooray!’! I’m 75 years old and I outlasted the wait. Nashville should be a little more accepting of this music than it was in ‘73, only because the credibility of the music that comes from Nashville is dramatically flagging because of its substances, themes and baby-faced messengers who haven’t lived long enough to successfully write and sing about it with any sense of credibility.”

Lastly, how do you feel about the record now that it is finally out?

“I am ecstatic that it’s out and warm heartedly thank Drag City Records for the catching the vision of a wild young man of the early 70s who never quit, who had the energy of three or four artists, who wildly danced through the years and never stopped trying to make a difference, and still to this moment of breath is trying to make true art out of respect to those who listen and to the God who gave me the gift.”

Interview: Duncan Haskell

At The House comes out on 17 November via Drag City. For more on Chris, go to: chrisgantry.com

Enjoyed this unique album. Thank you for sharing to the world.