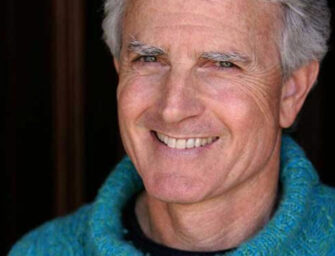

The preeminent lyricist and musician is back with a collection of songs enriched by her life experience and unique voice

Rosanne Cash recently returned with her first new album in nearly five years. The songs on She Remembers Everything, all written or co-written by Cash, directly and deliberately come from a uniquely female perspective and address issues from the personal to the political. Production duties were shared between husband John Leventhal and Tucker Martine and further help came from recognisable names such as T-Bone Burnett, Elvis Costello, Sam Phillips and Kris Kristofferson.

It’s yet another strong creative statement from Cash in a career which started back in 1978 with her self-titled debut album. Her many highlights along the way include Seven Year Ache, Interiors, Black Cadillac and The River & The Thread. These records tackled themes such as divorce and death and revealed her ability to remain authentic in different genres, such as new wave and roots – she’s not just a country artist. We recently had the chance to chat with Cash about her new album and songwriting career…

Are you still compelled to write songs on a regular basis or do you have set aside time?

“I would say my compulsion, if that’s what you want to call it, is still very strong. It’s funny, I can’t really separate that from my life. It’s like asking, ‘Do you still have a compulsion to breathe?’ Writing songs is at the centre of who I am. It’s not something that’s outside of my life which I have to set aside time for, it’s something that is so woven into my life.”

How do you know when the time is right to record and release a new album?

“Well, that’s funny because I wanted to put out this album sooner than I actually did but I realised that I didn’t have all the songs in place so I wrote a couple more. Those last couple of songs, Everyone But Me and Crossing To Jerusalem, John [Leventhal] and I wrote while we were recording the other songs; he wrote the music and I wrote the lyrics. So those were very late entries to the process.

As well as John, you also worked with Sam Phillips, T-Bone Burnett, Lera Lynn and others on the album. How does that collaborative process tend to work?

“Well, it’s different every time. With Sam, I asked if she wanted to write a song with me and she said yes and that she was more comfortable writing the music. That was great because I prefer to write the lyrics. I wrote the lyrics, finished them, edited them, got them how I wanted them and then emailed them over to her. In a couple of months, she emailed me back with her singing my lyrics to the music that she’d written and I was thrilled. I thought it worked perfectly.

“With T-Bone, he was music director on the television show True Detectives and asked me to write some lyrics for it. He gave me a theme and I wrote the lyrics to both The Only Thing Worth Fighting For and My Least Favourite Life.”

What’s the key to having a successful relationship with another – is it more important to be tactful or brutally honest?

“Well, you have to be honest. I’ve written songs with people when it just didn’t work and I’ve had to say something. A couple of times it’s been awkward but I don’t want to just throw my name on something. It’s different with John, he and I have worked together for so long and know each other so well that we can say things to each other. He might say, ‘That’s too many syllables for that line, I can’t make it work,’ or I’ll say, ‘I don’t really like that melody.’”

Can the closeness you have with John cause issues when it comes to your writing – is it hard to write about your relationship if he’s producing you?

“As long as we’ve been together, I can still feel a little shy. I wrote a song about him not many months ago and I felt a bit shy about playing it for him and didn’t want to ask him to produce it. So I asked Tucker [Martine] to produce it and it turned out great. Then John ended up hearing the finished track and I said, ‘Will you put your Telecaster on it?’ because of all the references through the song.”

Rosanne Cash: “You know, one reason why I think that I’m able to do this is that I believe in my own legitimacy.”

Not Many Miles To Go feels like a song which could only be written by someone who has lived a life and been in a relationship for a long time. Do you feel that you gain more breadth and depth as a writer the more experienced you get?

“Absolutely, I mean if you stay open and aren’t shutting yourself down year on year then you have more experiences to share and there’s more subtlety to those experiences. There’s less judgement and less need to please people. There’s also more poignancy. You can only write that song if you’ve been in a relationship for a long time and I had the realisation that one of us is inevitably going to leave the other and that’s so incredibly sad. I started thinking about all the little touchstones of our life together and the artefacts of our lives… the Telecaster, his glass of bourbon at the end of the day and the Empire State Building, which we can see outside of our bedroom.

“I wanted to litter this song with all of those things which have resonance in our lives, all those little things that will actually survive us and are going to be around long after we’re gone. There’s some comfort in that – we enjoyed those things, those were part of us, but can now be passed on.”

You’re talking about things which are very specific to your relationship but they seem to take on a universal meaning…

“I think so, because even if it’s not a Telecaster or the Empire State Building, there are specific things to other people’s lives that have resonance for them and that’s the part that’s conveyed. Everyone has those artefacts that will outlast us and will still carry a piece of us –whether it was your mother’s china or the diamond earrings that you give to your daughter. So I think that’s what becomes universal.”

We live in a world which seems increasingly obsessed with youth and therefore not everyone has the chance to mature as an artist, yet the things we’re talking about couldn’t have been written by someone new…

“You know, one reason why I think that I’m able to do this is that I believe in my own legitimacy. I don’t think that because something is new and fresh it’s more important. I’m not pretending to be 25, I don’t want to be 25. I think that people my age, middle-aged people, start to get insecure. Like, ‘Wow we’re out of 21 the race, we no longer matter,’ and that’s so not true and I’m just planting a flag in the ground for that.”

Another thing we wanted to talk with you about is the fact that we receive a lot of press releases where artists are described as a ‘female songwriter’ yet we never see anyone describing themselves as a ‘male songwriter’ – is that something you’re comfortable with?

“I know, I really don’t like that. I don’t like ‘women songwriter’ or ‘women musician.’ In a way it has an implied insult in it because it makes women a subset, like we’re not part of the real songwriting group, we’re the b-team or anecdotal in some way. So I don’t like that designation, maybe there are other professions where you need to define men and women, but certainly not songwriting.”

Are you then comfortable saying that the themes of She Remembers Everything come from a female perspective?

“That’s different because it’s relating to the themes of this album. The themes of this album are a woman’s story, a woman of my age and experience. My own madness, rage, love and sense of mortality. I think there is a distinctly female theme to it. But that’s very different from separating myself into a different category of musician.”

Is it maddening to still be addressing some of these themes 40 years on from your debut?

“Well, it’s what presented itself to me as full of power and resonance and what was real and truthful when writing these songs. After the 2016 election every woman I know was devastated and churned up, it’s hard to believe that this is where we are. Then these recent Supreme Court hearings were crushing. I thought that progress goes in one direction but it turns out that it doesn’t, it requires a lot of dedication to keep it going. But this is not a political album, the songs are not overtly political and yet I think that all truthful art and music is subversive and is a political act. It can change people and can reveal their own life back to them.”

Do you take on that responsibility and try to provide a voice for the ostracised and disenfranchised or is it more of a by-product?

“It’s a by-product. I can’t do the former because I don’t have a hero complex. I don’t see myself as a saviour and I’m not on a mission to educate people. I’m an artist and a songwriter. What I do comes from a place of truthfulness and my own sense of storytelling. If those stories change people then that’s beautiful but I think having that first contrived idea would actually kill the art.”

Rosanne Cash: “I don’t see myself as a saviour and I’m not on a mission to educate people. I’m an artist and a songwriter.”

How does it feel then when people come up and say how much your work resonates with their own lives?

“My God, it’s so humbling. People come up to me and say they played a song from Black Cadillac at their parent’s funeral or that Interiors helped them get through a divorce or say, ‘Thank you for writing this it’s exactly how I felt, how do you know the words to my life?’ These are all things that people have said to me. Sometimes I get really discouraged, because it’s a tough life and a hard world, and then when I hear this it gives me courage.”

So when big events are taking place or you’re going through particularly tough times are you writing thoughts down or is it a more natural process?

“Just yesterday I wrote down some lines for something I’m working on but I often don’t know what prompted it or where it’s going. That’s the beautiful mystery of songwriting. You have a germ of an idea or a rhyme or something that rolls off your tongue and you get a piece of it and you think, ‘Where’s this going, what is this about?’ The more you write it the more you find out what it’s about and that’s one of the most satisfying experiences in the world.

Have songs ever revealed their true meaning to you further down the line.

“Oh yeah, I call those songs ‘postcards from the future.’ I wrote Black Cadillac before anyone had passed and then, sure enough, everyone started dying; my stepmother, my father and my mother. With She Remembers Everything I wrote that song with a prescient sense of rage before this all happened in America.”

Have there been times when you haven’t been able to write or haven’t wanted to write?

“After the birth of my children, I just didn’t have anything in me to write. The first couple of babies really frightened me, I thought my writing life was over, but then it comes back. Having a baby and caring for a baby takes enormous creative energy, and rightfully so, all of the energy goes into nourishing that baby. Then gradually the energy that would go into your work and your writing comes back. I’ve seen that cycle and had it reappear throughout my life, so it doesn’t worry me. Sometimes you go through a period where nothing makes sense, ‘I’m just writing crap. I hate what I’m writing.’ and then there’ll be a breakthrough.”

What would your advice be to anyone who is struggling with their own creative dip?

“The dangerous part is that if you’re going through months of writing crap and not getting anywhere, some people give up and say, ‘Well I’m not any good,’ and then the critical voices in your head take over and you stop. That’s the worst thing that can happen. Just keep going, keep turning over those lines, save them in a notebook and go back to them later on. Maybe there’s the germ of an idea that you missed the first time. You have to be dedicated. It’s not all inspiration; it’s a lot of discipline.”

How do you know when you’ve written a good lyric?

“I know right away. I can’t tell you how I know, but I know. I honestly do not need anyone to tell me if a lyric is good or not. Also, what is good? If you went through the lyrics of Leonard Cohen’s Hallelujah, which I think is one of the greatest songs in pop music, you’d go, ‘Well that doesn’t make sense,’ and yet that song is elevated to the highest level of art.”

Bringing it back to She Remembers, how do you feel about it having had a bit of distance from it?

“I feel really proud of it. It was a risk, a lot of people said I should repeat what I did on The River & The Thread and make an album rooted in Southern music but I didn’t want to, I wanted to write these songs that were in my heart and flesh them out in a way that I heard them. I don’t know if it will do as well commercially but I feel so satisfied with what I did that it doesn’t matter.”

Interview: Duncan Haskell

Related Articles