The story of a small-town girl and city boy who headed to Hollywood becomes the “Biggest Song of All Time”

When Journey’s Jonathan Cain, Steve Perry, and Neal Schon wrote Don’t Stop Believin’ for the band’s seventh studio album, Escape, they couldn’t have anticipated the monumental impact it would have. Over 40 years later, this rock anthem, which can’t even be contained by the biggest arenas, is arguably more famous than Journey themselves. Thanks to constant radio play, cover versions, and its ability to capture emotions on screens big and small, it has remained a constant presence for the last five decades.

Its cultural impact is undeniable. Both a cornerstone of the early success of the TV show Glee and a vital part of the infamous final scene of The Sopranos, Don’t Stop Believin’ has also been adopted by sports teams such as the Chicago White Sox, Detroit Red Wings, and San Francisco Giants. With such wide appeal, it’s no surprise that, in 2022, the Library of Congress selected the song for preservation in the United States National Recording Registry. Named the “Biggest Song of All Time” by Forbes, the single is also certified 18-times Platinum.

In this extensive interview with songwriter, keyboardist, and rhythm guitarist Jonathan Cain, we delve into the story behind a megahit that was inspired by some fatherly advice and refuses to cut to black.

Article first published in Songwriting Magazine Summer 2024

Released: 19 October 1981

Artist: Journey

Label: Columbia

Songwriters: Jonathan Cain, Steve Perry, Neal Schon

Producer: Kevin Elson, Mike “Clay” Stone

UK Chart Position: 62

US Chart Position: 9

IT BEGINS WITH MY FATHER…

“It begins with my father, five years before I joined Journey, so that’d be in the 70s… 75/76. I was a singer-songwriter and I was on Bearsville Records, which was part of Warner Brothers, I had an album come out and then they dropped us rather suddenly.

“I was out of sorts, so I got a job selling stereos. I didn’t want to work in the clubs. I was barely making ends meet, and I needed a loan from my father. So I called my dad and said, ‘I need a little money to get me by. Should I come home to Chicago and forget this whole thing?’ And he said, ‘I know it seems tough right now but I believe the greatest blessing is just around the corner, so don’t stop believing Jon.’

“I was doodling and I had written his advice on the back page of this spiral notebook that I used to write my lyrics in. It was just something that I would look at from time to time and say, ‘My father really thinks something good is gonna happen here.’

“I continued to sell stereos until I was writing with this Englishman, Robbie Patton. I went over to this house he was renting and was very impressed. He had been writing with Christine McVie and was pretty plugged in. He told me about The Babys audition, that they were looking for a new keyboard player.

“I looked at their album cover, and I said, ‘Oh my God, they wear makeup and earrings.’ They looked like a glam band to me. He said, ‘You’ll like the singer’ That was John Waite. I played the album and really liked the sound, so I learned the music, went to the audition and they hired me.

“Going to Europe and playing with The Babys, doing two albums with them, was a great experience. It’s where I learned my rock and roll swagger, because you have to have a certain confidence when you walk on stage. To be a rock star you have to walk like one and think like one.”

I THOUGHT THEIR SONGS WERE LACKING IN PERSONALITY…

“We opened up for Journey in 1979 and I got to watch the band. The Babys had a pretty tight rock and roll set. So, I find myself opening up for Journey and watching these guys. I noticed the quality of the music, the playing was so good, and their extraordinary sound. Steve [Perry]’s voice was exceptional. But I thought their songs were lacking in personality. I watched them for 40 shows, I guess. I wanted to keep seeing what they were about. I was curious.

“Then, I was driving home one night after a gig, and the manager let it out of the bag, ‘What’s it going to feel like to be the next keyboard player of Journey?’ just kind of teasing me. I get a call that summer from the manager, ‘You’re the next guy in Journey.’ I said, ‘Where’s the audition?’ he said, ‘There isn’t one.’ So I packed my stuff from LA and go up to San Fran. They picked me up, found me a flat and rental car and told me I was going to make the next album with Journey and it was going to be called Escape. I was told to get with the lads at the rehearsal hall and get busy.

“Getting from The Babys over there wasn’t an easy task. I had to ask John. I said, ‘I think I have to do this. This seems like a really great opportunity.’ So he said, ‘You should take this gig,’ which I was grateful for. The other guys weren’t so happy about me leaving. But I called every one of them and told them…

“So off I go. Writing songs with Neil [Schon] and Steve. I hadn’t played a gig with them yet, but there I was writing songs. It was a remarkable time. When I got up there, to San Francisco, I found out that Steve Perry was a big fan of mine. He really liked my playing and writing, and the fact that I could play guitar and sing backgrounds.

“We were making this album and it’s going pretty well. I loved Steve’s singing and I said, ‘I watched you guys as a member of The Babys and I think what’s missing is you singing to the fans. You’re not singing about their lives, like Springsteen does, and I think it could really benefit Journey.’

“I wrote the first song with those guys, Keep On Running. It’s Journey singing to that blue-collar, hard-working guy that comes to see them and, boom, it works. Steve can deliver it and he sees what I’m saying right there. Then came Still They Ride. It’s an homage to cruising. They rule the night, these guys that drive around in their cars, trying to capture the old days.

“It’s tremendous and Steve can feel it. He’s been waiting to sing these lyrics. The album is going pretty well. Mother, Father, we write with Neil’s prog rock stuff. He gives me four cassettes and I’m putting together pieces from what I hear. I show it to Steve and I said, ‘I think this is the verse and this is the chorus,’ and I said, ‘It sounds like a song about this kid wanting his family to stay together.’”

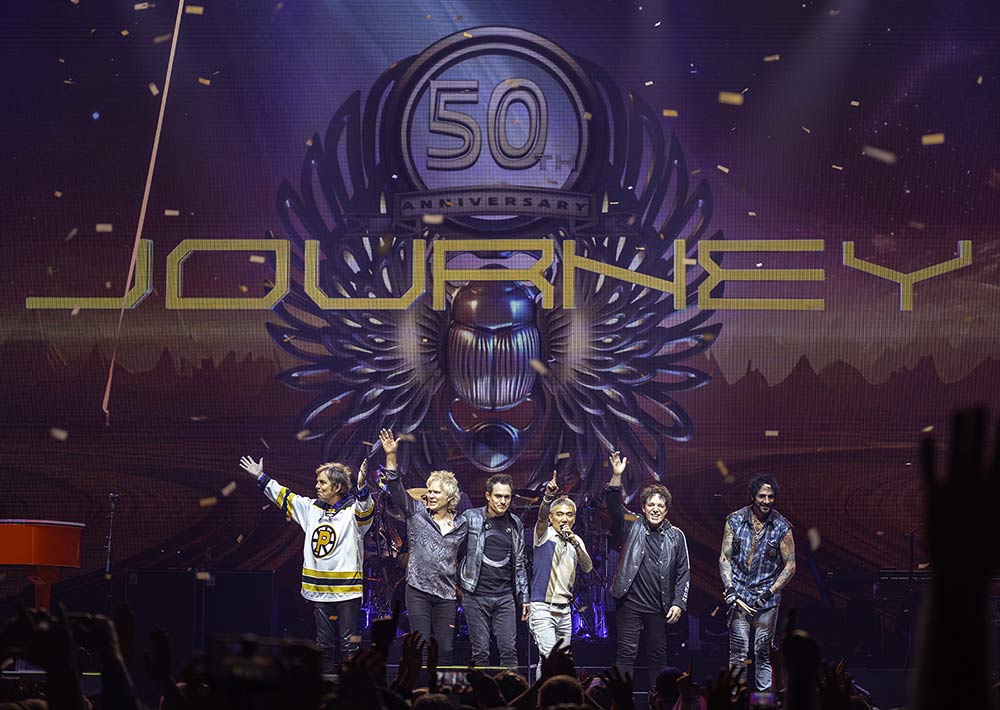

Journey’s Jonathan Cain: “We didn’t know there was no such thing as South Detroit.” Photo: Mike Savoia

WE NEED ONE MORE SONG…

“We’re almost done and Steve Perry says to me, ‘There must be something else in that book of yours? We need one more song.’ We only had a couple of days left. So I go home and I see this thing my father had said to me back in the day when I was struggling selling stereos, ‘Don’t stop believing.’ It’s a doodle on the back page and I said, ‘You know, he’ll sing this. That sounds like Journey.’

“I had a piano and I just closed my eyes, and boom, I heard his voice and out comes this chorus and these chords and everything – in 10 minutes. I recorded it on a little cassette so I wouldn’t forget it, but it was that memorable I didn’t ever play it. I brought it into the studio the next day and they all loved it. Steve said, ‘You know those chords that you have in the chorus, we could use those for the verse.’ He said, ‘Just add that little eighth note thing that you did in The Babys,’ So I started doing this thing and all of a sudden he starts [singing the melody].

“Then Neil started playing this bassline on his guitar and showed it to Ross [Valory] and then he comes up with this angular B section. And I’m like, ‘This is going well.’ Steve Smith comes up with this drumbeat. Everybody’s contributing something. It was a kind of a supernatural afternoon. We all knew each other so well, and we toyed around with this and that.

“The most interesting part of the afternoon was that Steve didn’t want to put the chorus until the very end, but Neil wanted to play that melody. So he jumped on the melody right away, before we ever got a chance to sing, ‘Don’t stop believin’’’ Steve said, ‘That’s really great. Play that melody and then we’ll sing it. They’ll lose their minds, because they only hear it these few times and then the song’s over. They’ll want to play the song over and over and over.’

“It breaks all the rules. Most songs have many choruses, you’ll hear it two or three times. Sometimes they’ll even put the chorus at the beginning – not this one. This one unfolds like a story. In between the verses, Neil impromptu starts playing this ticker-ticker, ticker-ticker, ticker-ticker thing. I didn’t tell him to play that.

“I had my trusty JVC tape recorder and bring the tape to Steve’s house the next day. We’re listening to the scat, because he was just scatting the vocals – we’d fill in the lyrics later. That ticker-ticker thing that Neil does, I said, ‘Steve, it sounds like a train.’ So it was, ‘The midnight train to… Georgia… the midnight train going…’ and Steve goes, ‘Anywhere!’

“I said that at the beginning we needed a small-town girl and he goes, ‘Yes, city boy. Born and raised in… it’s got to be Detroit.’ I said, ‘Why’s it got to be Detroit?’ He said, ‘Well, we just played Cobo Hall and made a live record there and they love us.’ So he goes, ‘Is it going to be East Detroit, West Detroit, North Detroit?’ I said, ‘Sing them all, see which sings best.’ When he got, ‘South Detroit,’ that was it.

“We didn’t have Google then; we didn’t know there was no such thing as South Detroit. It just sounded good. Later on, critics would bust me out and I’d say, ‘No, that’s an imaginary city that doesn’t exist. It’s a city of possibility.’ That would shut them right up.”

IT TOTALLY BECOMES THIS MOVIE…

“When it got to the B section, the sort of pre-chorus/ ‘strangers, waiting…’ I said, ‘This sounds like Sunset Boulevard.’ I told him I’d lived in Laurel Canyon for eight years and, when I wasn’t working at a club, I’d go down there and watch this crazy carnival/circus thing. The guys cruising, hustlers, actors, actresses and wannabe rock stars – everybody converging on Sunset on a Friday night. And he said, ‘That sounds amazing.’

“‘I said, ‘It’s strangers up and down the boulevard.’ Then we came up with, ‘Shadows searching in the night…’ and it totally becomes this movie, it’s very cinematic. Being a Dylan fan, a McCartney fan, Springsteen, Elton… These are all cinematic songwriters and, as a big movie guy back in the day, my songs were like little mini movies. Even on my solo record, I wrote in that style. I felt like that backdrop really suited the song.

“Then we inserted ourselves. ‘Working hard to get my fill. Everybody wants a thrill…’ So Steve and I, we both came from clubs. He was playing clubs. I was playing clubs. So we inserted ourselves in the movie. The singer in a smoky room, that was Steve. We put ourselves in there.

“We had this whole bookend thing, this exterior of Sunset Boulevard and all these little vignettes. There’s the city boy and the small-town girl getting on the midnight train going anywhere. Of course, they’re going to end up in Hollywood, on Sunset Boulevard. It was pretty easy, once we got that far, to really expand upon the permission to dream idea. You know, ‘You’re not stuck where you are.’

“The reason it succeeds on many levels… even at the end of The Sopranos when they’re sitting there listening to Don’t Stop Believin’, they somehow are free from that. Because that song just opens it up and it says, ‘You can get on a midnight train going anywhere!’ We don’t know if Tony Soprano survived that scene or not. But David Chase did that on purpose, because he wanted that open window of the midnight train going anywhere.”

Journey’s Jonathan Cain: “It breaks all the rules.” Photo: Mike Savoia

WE COULDN’T GET IT RIGHT…

“All the songs on Escape went out pretty quickly. We were able to get them in one or two takes. When it came to that song, Don’t Stop Believin’, it was fussy. We couldn’t get it right; we’d always speed up or slow down once the drums started. It was sort of a relay race where I’d hand the baton to Steve [Smith] the drummer and he’s got to take it from there and make it feel smooth – but there was that transition wrinkle.

“I remember the day we recorded it, Steve [Perry] had a cold and wasn’t feeling well. We had been at it most of the afternoon and hadn’t got the take. So I sent Steve home, I said, ‘You should go home. Come back next week. We’ll get this, I know what to do.’ So he left. The producer Mike Stone had one of those click track things and I said, ‘Turn it on for a second, we’ll dial it in.’ We played with a click, maybe two takes. It was very wooden and felt very stiff, but that transition got seamed up and smoothed out.

“So I said, ‘Now turn it off and let’s cut it.’ So we turned the click off and something magic happened – that perfect handoff. I remember, it’s five o’clock that night, Mike’s really happy, we’re all grooving like, ‘This is amazing.’ Then he put this chorus on my piano, this kind of wobbly thing. I’m like, ‘That’s genius. I love that.’ He’s got this bass singing, almost like a cello or something.

“Mike Stone was a genius. Not enough has been said about how good he really was. He did the Ace record, How Long and that was the sound that Steve and I were looking for. When we heard Paul Carrack singing that… When I heard that single, I said, ‘That’s the Journey sound for this record.’ So we got hold of Mike, he’s got time, and he’s this lovely English guy – almost as crazy as Roy Thomas Baker, but not quite as off the wall.

“Journey, we were so rehearsed. We were like the Eagles, we rehearsed every day for five days a week. So when we went to make these records, our basic tracks were cut in a week. I think Escape was $80,000 in four weeks. Album done. Not one A&R guy sets foot in the studio, nobody shows up from Columbia. Nobody, because it’s off limits. Our manager said, ‘We’ll give you a record when it’s done. We got four singles on this. Don’t worry about it. We got it.’

“Steve and I always had radio in mind. When we made an album we had our progressive, Neil Schon rock stuff, and then we had our singles. When I met Steve, the first couple of weeks we wrote he said, ‘What really turns me on is being on the radio.’ And I said, ‘Well, you hired the right guy because I’m with you. I want to be on the radio.’ So when Who’s Crying Now came out as the first single and went Top 10 it was like, ‘We’re on the radio!’

THERE’S STILL CITY BOYS AND SMALL-TOWN GIRLS…

“I can’t say enough about how much that song did to give our fans a reason to stay involved with us. Not only that, but you get people that get depressed and then they play that song and they’re like, ‘I’m okay now.’ During COVID, when people made it and would get wheeled out of the hospital, they’re playing that song on speakers for them and they’re smiling. Those kind of moments… Music is a great healer.

“The Library of Congress is a pretty big deal, to get acknowledged by such a prestigious group, that means a lot. But it takes the fans to react, it takes them to approve.

“I think the reason it’s lasted the decades that it has is because there’s still city boys and small-town girls wanting to get on the midnight train going anywhere. It’s a universal idea; things might be bad, but you can change your situation. You can move out. I moved from Chicago. I knew that I wasn’t going to make it there. I had to go where it was happening. And that was Hollywood. If I had stayed in Chicago, and tried to be a big-shot there, nothing would have happened with my career.

“I had to get to LA and I gave up a lot of my friends and my brother, family… I left them all. Back in those days, that was a long way away. I didn’t get back to Chicago much. It was expensive to fly there. But I had my dad’s permission to keep on it, and it really worked great.

“The greatest part of that song for me is, I was on the outside looking in on the rock and roll lifestyle. I’d had a taste of it. The Babys was the beginning but I never showed Don’t Stop Believin’ to John Waite. I don’t know why. It was there, could of. It just sat there because it was waiting for Journey, this idea. And then Steve asked me, ‘Do we have one more song?’”

Related Articles