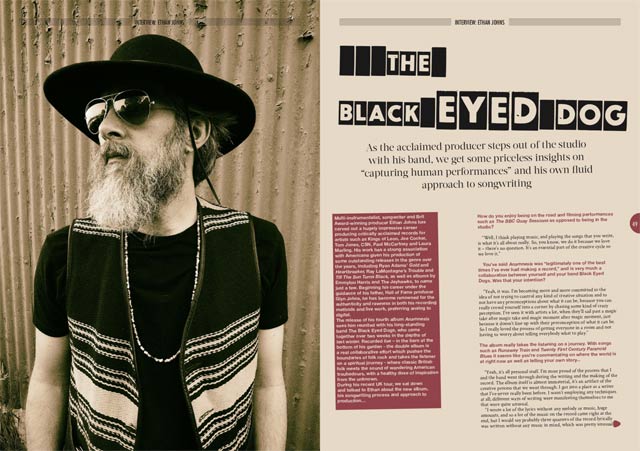

Black Eyed Dog: The acclaimed producer shares priceless insights on “capturing human performances” and his own fluid approach to songwriting

Multi-instrumentalist, songwriter and Brit Award-winning producer Ethan Johns has carved out a hugely impressive career producing critically acclaimed records for artists such as Kings of Leon, Joe Cocker, Tom Jones, CSN, Paul McCartney and Laura Marling. His work has a strong association with Americana given his production of some outstanding releases in the genre over the years, including Ryan Adams’ Gold and Heartbreaker, Ray LaMontagne’s Trouble and Till The Sun Turns Black, as well as albums by Emmylou Harris and The Jayhawks, to name just a few. Beginning his career under the guidance of his father, Hall of Fame producer Glyn Johns, he has become renowned for the authenticity and rawness in both his recording methods and live work, preferring analog to digital.

The release of his fourth album Anamnesis sees him reunited with his long-standing band The Black Eyed Dogs, who came together over two weeks in the depths of last winter. Recorded live, in the barn at the bottom of his garden, the double album is a real collaborative effort which pushes the boundaries of folk rock and takes the listener on a spiritual journey – where classic British folk meets the sound of wandering American troubadours, with a healthy dose of inspiration from the unknown.

During his recent UK tour, we sat down and talked to Ethan about the new album, his songwriting process and approach to production…

How do you enjoy being on the road and filming performances such as The BBC Quay Sessions as opposed to being in the studio?

“Well, I think playing music, and playing the songs that you write, is what it’s all about really. So, you know, we do it because we love it – there’s no question. It’s an essential part of the creative cycle so we love it.”

You’ve said Anamnesis was “legitimately one of the best times I’ve ever had making a record,” and is very much a collaboration between yourself and your band Black Eyed Dogs. Was that your intention?

“Yeah, it was. I’m becoming more and more committed to the idea of not trying to control any kind of creative situation and to not have any preconceptions about what it can be, because you can really crowd yourself into a corner by chasing some kind of crazy perception. I’ve seen it with artists a lot, when they’ll sail past magic take after magic take and magic moment after magic moment, just because it doesn’t line up with their preconception of what it can be. So I really loved the process of getting everyone in a room and not having to worry about telling everybody what to play.”

The album really takes the listening on a journey. With songs such as Runaway Train and Twenty First Century Paranoid Blues it seems like you’re commentating on where the world is at right now as well as telling your own story…

“Yeah, it’s all personal stuff. I’m most proud of the process that I and the band went through during the writing and the making of the record. The album itself is almost immaterial, it’s an artefact of the creative process that we went through. I got into a place as a writer that I’ve never really been before. I wasn’t employing any techniques at all; different ways of writing were manifesting themselves to me that were quite unusual.

“I wrote a lot of the lyrics without any melody or music, huge amounts, and so a lot of the music on the record came right at the end, but I would say probably three-quarters of the record lyrically was written without any music in mind, which was pretty unusual for me because usually it comes at the same time. But what it did was it really freed me up.

“I’m constantly trying to get out of my own way, and allow things to flow and be natural, be non-judgmental about what I’m doing and let it come. So I will write pages and pages and sometimes only use a few lines. Sometimes those ideas would go on the shelf for a few weeks or months, and then you might find that you’ll enter a new idea that relates to that. Then I would go back to that set of words and I would add to them and then edit them down.

“It was fascinating… Some songs came in literally in the classic 20 minutes: pick up a guitar and bang, all of a sudden you wake up and you go, ‘Oh my God it’s finished!’”

Did you write in the studio or were the songs for the record completed beforehand?

“There’s a lot of room for improvisation and changing things in the studio. I’d say in terms of writing, the band brought a lot to the table while we were fleshing these things out. I didn’t have ideas for some things; I didn’t know if they were going to have drums or not. In terms of melodic things and structurally: structurally they definitely had ideas, some were fairly watertight, others were not at all.”

Ethan Johns: “The most fun records that I’ve made were done really fun and really fast and almost for nothing.”

Would you say there’s a blueprint for the perfect song?

“No such thing. The perfect song is whichever is the most honest expression at the time. There are so many. To me, it’s just too wide open. There’s a lot of improvisation on this record too, so actually a lot of the arrangement decisions that were going on, we were making on the fly. So when you talk about perfect song structure, I love the idea that things can be fluid.”

Is there a song you wish you’d written?

“I wish I’d written Time (The Revelator) by Gillian Welch, which is one that we do play fairly regularly.”

I remember seeing you perform it live at the UK Americana Awards. Fantastic.

“It’s an amazing song. Unbelievable.”

With artists that you have worked with, do they tend to come into the studio with finished songs, or do you like to help them develop ideas throughout the recording process? I imagine it does depend on the artist.

“Every artist has a different set of requirements, yes, so it really is different with everyone. That is one of the reasons why production is so interesting to me because it’s never the same job from day to day.”

So do you have a similar approach with every artist, or do you adjust to suit his or her style?

“Absolutely. Yeah, you have to be completely simpatico with the artist that you’re working with so, like I say, what the situation requires is going to change all the time. I’m not a formulaic guy, I’m about as far away from being formulaic as possible. I like to record live, I love throwing things to chance and looking for moments of inspiration that are not planned.”

As you’ve said before, it’s about “capturing human performances.”

“Very much. The honesty thing is what I’m looking for. Of course, it’s all in the eye of the beholder because I’ll respond to a take. I remember one of the most devastating takes with a song on A Creature I Don’t Know [by Laura Marling]. We’d had dinner then Laura walked in, picked up the guitar and Don, the engineer, was very switched-on and pressed record on the tape machine.

“She didn’t know that we were recording and she sang. It’s just an extraordinary song and it’s an incredible rendition. I’m standing there and within a couple of lines I’m going, ‘Oh my Lord, I hope she doesn’t stop!’ It was so magic, but when she finished the take she immediately started reaching for her capo and muttering to herself, ‘Oh it’s not the right key.’ So I can imagine she’s probably thinking about everything but actually singing the song and yet, what’s coming out is extraordinary. So again I think that’s probably a great example of not trying to control everything and all of a sudden it really starts to flow.”

Before you’re about to produce a track or an album, how do you like to hear the raw material? I guess that again varies.

“It does but I do like really really basic demos more than really overworked stuff, even though it doesn’t matter. I prefer to get to the core of the song, generally speaking, it’s what I’m going to want to hear more than someone who’s spent three months on a Pro Tools version – they may as well just put that out.”

Interview: Lisa Redford

Related Articles