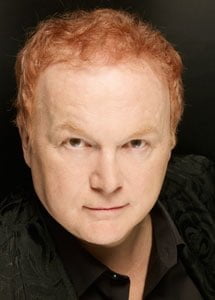

Mike Batt: “My music seems to have a kind of melancholy to it… which is weird for the bloke who wrote The Wombles!”

The man behind The Wombles’ chart success, the writing of Art Garfunkel’s ‘Bright Eyes’ and the discovery of Katie Melua

hroughout a career spanning more than 45 years, Mike Batt has indulged in the successes of songwriting, production, performance and composition. Having enjoyed chart success, clocking up eight hit singles and four gold albums with The Wombles, Batt went on to write some of the country’s most memorable pop singles, notably Art Garfunkel’s international number one single Bright Eyes, Caravan Song performed by Barbara Dickson, and a slew of hits for artists including Cliff Richard, David Essex, Alvin Stardust.

hroughout a career spanning more than 45 years, Mike Batt has indulged in the successes of songwriting, production, performance and composition. Having enjoyed chart success, clocking up eight hit singles and four gold albums with The Wombles, Batt went on to write some of the country’s most memorable pop singles, notably Art Garfunkel’s international number one single Bright Eyes, Caravan Song performed by Barbara Dickson, and a slew of hits for artists including Cliff Richard, David Essex, Alvin Stardust.

His solo career included two albums, Schizophonia and Tarot Suite, both of which were with the London Symphony Orchestra and he achieved new heights of success as a solo artist when his single Summertime City made the number four spot. Recent years have witnessed Mike dedicate most of his time to the careers of other artists including Vanessa Mae, Anna Maria Kaufmann, Bond, The Planets and Katie Melua and running his record label Dramatico.

Songwriting caught up with Mike to reflect on this remarkable music career from writing silly poems as a child, a short spell in A&R, his ridiculous success with The Wombles and how his somewhat unusual pairing with Katie Melua worked so well…

What were your first memories of making music?

“I think it started with words with me. When I was a kid I used to be interested in writing poems, for some reason. I was about nine years old, so I started late – I never did piano lessons when I was five years old, or anything like that – but I was always interested in the words of A.A. Milne, Winnie The Pooh and stuff like that. I remember writing a poem, when I was about nine, that got in the school magazine. It was a silly verse really called A Man From Armada.

How did it go?

“It went something like: ‘A man from Armada was searching his larder, a jam tart for to find / he was very cunning, he saw someone coming, and hid it behind his behind!’ That was my first opus and of course it’s almost obscenely naïve. Anything like that would catch my attention. Also, my best musical memory was my dad had bought a piano from a junk shop – he wasn’t a piano player by any stretch of the imagination; he could play a few tunes on the black keys – but I did try and pick it up and taught myself how to play. One of the very first things I did was take an A. A. Milne poem, James James Morrison Morrison Weatherby George Dupree and put that to music. And so I suppose my childhood was laced with opportunities to pick up on verse, particularly verse that had clever lyrics, which I think Milne was a master at, and so was Lewis Carroll. And music which had some kind of emotion. I don’t quite know where I got that from, but over the years people have said my music seems to have a kind of melancholy to it… which is weird for the bloke who wrote The Wombles!”

Mike: “I’ve always wanted too many things”

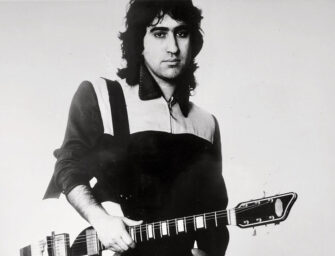

“Yes. When I was 18, I’d become the member of an R&B group in Southampton and was reading NME on the bus there. The advert was ‘Liberty Wants Talent’ and that was the same one that Reg Dwight and Bernie Taupin both answered, independently, without knowing each other. Ray Williams was the young A&R man who was starting up Liberty – which became Liberty/United Artists – who put the ad in and I was one of the so-called talents that went along.”

What sort of talent were they looking for?

“I think Ray was just a young, mover and groover on the scene and he wanted do some signings, so put it out there that he was looking for things. I’d never seen an advert from a record company actually wanting talent; it’s usually, ‘clear off, we don’t want it’! Anyway, I got an appointment and he saw me, I played him one of my own songs that I’d written, on a reel-to-reel tape, and he was very receptive. He suggested that I met the publishing director, Alan Keen, and he signed me to a contract that was very far ranging – it didn’t have any money attached to it. In fact, it did me a favour because a year later when I wanted to leave, I was able to walk away from the contract because it was so unfair. But when I signed it, I felt like I’d conquered the world. When a big record company offers to sign you up, at the age of 18 years old, you pretty much sign anything! I was a professional songwriter, even though I hadn’t earned a penny from it.”

Were you signed as a solo artist, or a behind-the-scenes songwriter?

“I signed to Liberty to be Mike Batt, and with them as a publisher, and several singles came out. Then I was asked to be their A&R director, which was weird, for an 18-year-old kid to be given that responsibility. It was a good 18 months of my life as head of A&R; I worked with Canned Heat and Creedence Clearwater Revival. Lots of big acts came through from America and so I had a lot of experience working with other acts and producing the odd record myself as well.”

Mike: “A business card with Liberty Records and your name on it was great for pulling members of the opposite sex!”

Were going out to find talent?

“Well, the good thing about being a young A&R man in those days, where you’ve got a business card with Liberty Records and your name on it, you could get into any club in town – it was great for pulling members of the opposite sex! They paid me next to nothing, mind you, but I didn’t care. I had a good time, but mainly looking for talent – obviously the kind of talent to record. I remember when we signed The Idle Race, with Jeff Lynne of course, and they came in to listen to some songs. So I sat at the piano and played Jeff and his mates a few songs and I think they must’ve thought, ‘we can do better than that’ and went home and wrote their own.

“To be honest with you, I found it all a bit much trying to be an artist and a writer and an A&R man as well. It was great fun, because it was in the days when A&R men were record producers as well – people like Tony Hatch, although he was ahead of me in generational terms.”

Was there any point when you had to decide whether you were going to be an artist and songwriter, or carry on down the music business route?

“I always wanted to run a record company, but my problem is I’ve always wanted too many things! Obviously at some point you have to decide what one you want to be. So I did leave Liberty because I wanted to be a freelance arranger and conductor, and they were the two things I wanted to teach myself more about. So I learnt from textbooks and took any chance I got to be in a good studio with an orchestra or a string quartet. I used to do heavy metal and blues as well – I produced The Groundhogs, which were very big for Liberty at the time. So I had an awful lot of experience in a very short time.”

So you’re completely self-taught?

“Yes, to play the piano initially when I was younger and then eventually to read music afterwards. Because I learnt to play the piano by ear, but when I got into orchestration, I had to teach myself that.”

Over the decades you’ve developed an identifiable style. Were you trying to put your ‘stamp’ on your music, or was it just a natural development?

“Well, I don’t think you have to try. I’ve got friends who are rockstars or had lots of hits in a particular genre, and they’re worried about moving out of their genre and losing their public. But I never really had a public! I’ve never really been the frontman of a band, so I don’t feel as though I’ve got to write in a particular vein. So by being a jobbing arranger, songwriter, film-score writer or sometimes producing people – like I did with Katie Melua or Vanessa Mae – I’m tailoring the material to fit. I like working in so many different styles, but somehow your own style does come through and people can tell it’s you.”

Let’s talk about The Wombles. Was that the next turning point on your career path?

“I had wanted to produce a big, heavy metal-meets-orchestral concept album. It was a carefully conceived arty kind of rock, and it was written as a piece of music with great session players reading the parts along with the orchestra. I did the project and tried really hard to sell it. I almost went broke, spending any money I might’ve had and borrowing far more than I should’ve done to try and make it happen. I nearly pulled it off and nearly sold it to A&M Records for a huge amount of money and it dropped through at the last minute. Then The Wombles came along as a job, rather like doing a commercial.

Mike Batt: “I didn’t feel like I had to wear the cloak of pretentiousness in order to stay in the taste zone of my audience.”

“So I went along to the BBC to see what it was like and I said, ‘Wouldn’t you prefer a song where I can write about the characters so the kids will know a bit more about what they’re all about?’ And they said, ‘Yeah let’s try that.’ So I wrote the song and that was it really. But rather than them paying me the £200 they offered me, I said, ‘Can I have the rights to make a pop group out of The Womble characters?’ And they said, ‘No problem.’ I don’t think it was part of their business plan, but to me it was an opportunity to indulge my rather over-developed sense of humour and have some fun! And it gave me an opportunity to flex my muscles as an arranger.

“I really enjoyed it because I was very keen on The Beatles when I was growing up, so I could make The Wombles sound a little bit Beatle-y. But the bad side of it was that it did mean that I was seen as someone with a whimsical sense of humour and should be grouped with people like the Bonzo Dog Doo Dah Band, rather than with the progressive rock types that I’d considered my contemporaries.”

Did you find it difficult to be taken seriously then?

“Yeah, I think that’s what I’m talking about. It’s the clown who wants to play Shakespeare! I was always both really. I was into the fun, entertainment side of music – it goes back to me writing silly poems at school – so I was never ashamed of writing something a bit amusing. I didn’t feel like I had to wear the cloak of pretentiousness in order to stay in the taste zone of my audience. As a songwriter and a ‘free agent’, I was able to move between different genres and still write serious stuff when I wanted to.

“When I started out as a songwriter, I had in my mind the notion that some people could – and some people couldn’t – write hit songs. I knew I could write songs because I’d written them, but I hadn’t had a hit then. So when I was actually able to write a hit, which was The Wombling Song, it just happened to be that song.”

Would you say it’s important to have a good song title?

“I think titles are very important for songwriters. If you’ve got a good title, you’re part of the way there. When I was at the height of my work with Katie Melua and I was writing most of her stuff, I would often come up with song titles that would amuse her. For example, I remember sitting on a bus in China with Katie, being told all the facts about where we were going; pointing out the Emperor’s palace, that there were six thousand donkeys and nine million bicycles in Beijing… And I turned to Katie and said, ‘That’s a song title!’ She just burst out laughing and said, ‘You’ve got to be joking, how are you going to make a song about that?’ I said, ‘I don’t know, it just feels right.’

“I got home two weeks later, having scribbled it on a bit of paper, and went to my piano to write that song [Nine Million Bicycles]. To be honest, I knew it was a bit of silly title, but I thought you could juxtopose that silliness against something really important like the words ‘I will love you till I die’. It kind of appealed to my sense of the slightly ridiculous and I think for that reason it made it a more powerful song, emotionally.”

Mike: “Often you use your own feelings to write a song which is for someone else, because you’re a human being and so are they.”

How did you discover Katie Melua?

“I can’t remember when it was, but I thought: if I could find someone contemporary and younger than myself, who I could get to sing my songs, it would be useful. I’d always tended to write songs by myself and very rarely co-written things, so I was looking for someone who could really sing. I put an advertisement in several different music colleges like ACM [The Academy of Contemporary Music] in Guildford and I found a couple of people, did some auditions, but they weren’t quite right for what I was looking for. So I thought I’d try one more time and went to The BRIT School. Several people came and sang for me and one of them was Katie Melua. She was the second one in the room – her friend Polly Scattergood was the first, who was very good too. But in came Katie and I remember (I’ve still got the bit of paper somewhere) I wrote down: ‘Small girl, sang own song.’ So we went in the studio to see how it goes and sure enough, she delivered. The thing that made me think Katie was potentially great, rather than someone who could just have a hit, was when I asked her to ad lib across a particular song – I think it was September Song by Kurt Vile – and she came out with a way of singing it which was not out of the jazz book. It was definintely staight from her – it wasn’t copied from anyone or a standard embellishment. It was something very special and I started laughing with joy, that someone at the age of 17 had the ability to do that. So that’s how it started.”

Which was the first song you wrote for Katie?

“I had a song that I’d written some 12 or 15 years earlier than that called Closest Thing To Crazy and we tried her on it and she sang it so well. I remember taking it to a friend of mine at the BBC, with another half dozen songs, and saying, ‘don’t worry about listening to that one because it’s too slow for you guys, you won’t play it.’ I was going to take the song off the album, but the next day I got an email back from the bloke saying, ‘If you take Closest Thing To Crazy off the album, I’ll never speak to you again!’ He was the one who produced the Wogan show and, of course, he played it and that’s how we broke Katie.”

Looking back it’s clear you were a successful partnership, but it’s an unusual pairing. When you sat down to write songs for her, did you think about what Katie wanted to say, or were you still writing from your own point of view?

“If I’m writing for an artist, I will write with them in mind. In this particular case, it wasn’t – Closest Thing To Crazy was actually written for a musical called Men Who March Away, which I’m just about to put on in the next year or two. When I got to know Katie a bit more, I would write stuff that I knew would suit her. But very often you use your own feelings to write a song which is for someone else, because you’re a human being and so are they, so you can put yourself in their position. But I would never presume to write a song for Katie about an emotional situation she was going through, because that would be way too much.”

You tend not to collaborate. Is there a reason for that?

“There’s too much diplomacy involved. If someone comes up with an idea you don’t like, you’ve got to carefully explain why not. The first rule of co-writing is that if one of the people don’t like it, it doesn’t go into the song.”

Other than the A Classical Tale album and the musical, are there any other new projects in the pipeline?

“Yes, I’m also working on a Wombles TV series and each 10-minute episode will feature a Wombles song from the past. There were 50-odd songs so we’re taking them out and making the stories based around the songs. That’s a fun songwriting exercise.”

Interview: Aaron Slater

Following up the Top 30 hit album A Songwriter’s Tale, Mike Batt returns with A Classical Tale which is released 24 July on Dramatico Records. For more from Mike, visit his own blogsite: madhouserag.com

Related Articles