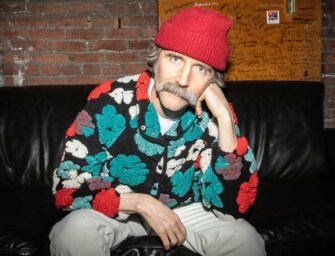

David Arnold: “Playing in school ensembles and college bands were things that got me excited about making a noise.”

The acclaimed composer of James Bond soundtracks, film scores and TV themes, shares movie songwriting insights and inspiring advice

he name’s Arnold… David Arnold. He may not have a license to kill, but the English film composer is well known for penning killer soundtracks to five James Bond films (Tomorrow Never Dies, The World Is Not Enough, Die Another Day, Casino Royale, Quantum Of Solace), a string of blockbuster movies (Stargate, Independence Day, Godzilla) as well as several successful British TV series (Sherlock, Little Britain). For his work on Independence Day, David received a Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Composition Written For A Motion Picture Or For Television and, for Sherlock, he and co-composer Michael Price won an Emmy. His list of accolades also include winning two Ivors – Best International Film Score and the BASCA Fellowship – and being nominated for several other awards along the way.

he name’s Arnold… David Arnold. He may not have a license to kill, but the English film composer is well known for penning killer soundtracks to five James Bond films (Tomorrow Never Dies, The World Is Not Enough, Die Another Day, Casino Royale, Quantum Of Solace), a string of blockbuster movies (Stargate, Independence Day, Godzilla) as well as several successful British TV series (Sherlock, Little Britain). For his work on Independence Day, David received a Grammy Award for Best Instrumental Composition Written For A Motion Picture Or For Television and, for Sherlock, he and co-composer Michael Price won an Emmy. His list of accolades also include winning two Ivors – Best International Film Score and the BASCA Fellowship – and being nominated for several other awards along the way.

Songwriting caught up with David in his studio, working on the music to a forthcoming Sherlock Christmas special, before preparing for a series of A Life In Song concerts across the UK in April and June. Joined by the some of the country’s top orchestras, the shows will take audiences on a journey with new and reworked performances of his best-known songs, scores and themes. David will also talk about his work, how the music came to be, and share anecdotes from his illustrious career, but here we get a sneak preview of the insights and useful words of advice for any budding movie theme songwriters out there…

What are your earliest memories of making music?

“When I was at school, other kids were playing instruments completely out of time, or were singing out of tune, and it was beyond me. I remember thinking it was really odd that they couldn’t hear beats and rhythm. I didn’t know what they were either, but it was like watching someone being unable to walk – I couldn’t figure out why someone couldn’t do that.

“I had some terrific music teachers and learnt about different instruments, harmony and melody. For me, playing in school ensembles and college bands were things that got me excited about making a noise – the noise that I would enjoy of someone on the radio, in concerts, or in films especially. You were there, listening and absorbing the sound and to find yourself being a part of a group – a body of people who created it – was very exciting. School orchestras were typically playing instrumental pieces – there wasn’t anyone singing – so I suppose I thought more instrumentally than I did about songwriting. But I was listening to a lot of songs, because growing up in this country you couldn’t avoid it. There was always a radio on at home and I wanted to be involved with music or films, so I believed I’d be a musician or an actor, or something.”

So the two came together, the love of movies and the love of music?

“Well, they went hand in hand. What I’m able to do now is very much what I enjoyed doing when I was really young, which was to be involved with making records, writing songs and film scores, TV work… Things that hopefully catch your ear and get you excited in what you’re watching or listening to. I’m doing all those things. I realise that’s a very rarified atmosphere that I exist in and I’m very lucky to be able to do that – it feels I’m making the sort of noise now that I would’ve done when I was six years old, which is great.

It’s interesting that you didn’t really have a classical upbringing or music training, which many people might would assume you had.

“No, not compositionally. I didn’t do a composition course or a degree, but I spent most of my school and college time playing in orchestras, so I had a good appreciation of how an ensemble works and how different tone colours of different instruments work. I read a lot of scores, I listened to a lot of classical music and I suppose the main thing I learnt, in terms of writing for film, was writing for film! I spent eight or nine years working, for no money, trying to learn how to do it. I suppose I sort of learnt on the job.”

[cc_blockquote_right] THE JOB IS YOU, IN A ROOM BY YOURSELF, WITH THE FILM, TRYING TO RESPOND TO IT [/cc_blockquote_right]

Given that you tend to create music on your own, you don’t have the same ‘feedback’ from an audience, like a performer or band would, so how do you know when it’s working?

“The thing about film is it’s not just about the music, so you never really get an audience’s appreciation of what you’ve done purely on the music. It’s only ever received alongside scripts, photography, acting and editing, and all of those things happen at the same time, so you’re considering the film as a whole. Obviously if people know the music and like the music then that’s something else, but generally it’s down to whether people think the film is any good.

“Luckily, I was scoring quite a lot of students’ films at the National Film & Television School, where they had a rigorous deconstruction of the success or failure of the work, by experienced people who would come in. It was interesting sitting in and watching professional film-makers tear apart everything that you’ve done. That allows you to understand the reasons why things work and how they work. It helps you appreciate and read a story and a scene and character – all these things are difficult to teach and to a certain extent you have to ‘feel’ it.”

Were you studying full-time then?

“No, during that time I was doing part-time jobs and temp work on building sites. I’d do two or three weeks working and then I’d take a few weeks to do a student film, or something. There was never any guarantee that anything was going to happen, but I knew that I wanted to do it, and if I didn’t do it the best as I could, then I’d never have a crack at it.”

How do you think things have changed since you broke into the business?

“Now there’s a certain access to the industry, through the technology that’s come on so fiercely. A composer’s assistant now has a huge amount that they need to know immediately, and could effectively learn how to do the job alongside the composers working with the same technology. But when I was doing that, it was very basic – everybody was still using video tape, primitive synths and synchronisers, and sequencers with only eight channels of MIDI available. So the sketches that you did for the directors were much cruder because you couldn’t realize it that fully, unless you had hundreds of thousands of pounds to buy outboard equipment and, of course, as a student you haven’t got that sort of resource.

“So the revolution in technology has made the job quite difference, but at the core of it you still need to know why the notes are there and what they’re doing.”

Do you still have a similar process when you approach writing the theme for Sherlock, as you did in the early days when you were writing for the film The Young Americans?

“I suppose the principle is exactly the same. I saw The Young Americans and I had to come up with the music for it, and that’s the same today. We started on the Sherlock special with Michael Price and we’ve got a show in front of us that requires music and it makes demands of us, creatively. It produces a huge amount of problems that need to be solved, musically, and that’s what I have to do. That’s not really any different from Sherlock to James Bond. The job is effectively you in a room, by yourself, with the film, trying to respond to it.”

When it comes to writing a more traditional theme song, like Play Dead, for example, do you treat that as a separate task to the film’s soundtrack?

“The track for Play Dead was the thing that I thought of first, and I didn’t think of it necessarily as a song, until we talked about having an end title piece. So I didn’t write it for the film as a song. That chord sequence that was the opening of Play Dead was what I came up with as a motif and it starts the film off as well, when Harvey Keitel’s character is coming into land in London. It’s those mournful strings, oozing over the throbbing bass – I think it was an old Matrix 1000 – and it felt introspective and dark, and felt like something was going to happen.

“Then we started talking about perhaps turning into a song and who we could do it with. I’d been listening to a lot of Jah Wobble and Björk, from the thing she did with 808 State and The Sugarcubes, so we asked Jah to play some ideas and Björk literally lived around the corner. We asked if she was interested and she come over and we played her the track, and she said she’d do it.

David Arnold: “I like to come up with ideas on my own first and then share them… I hate going into the room for a songwriting session.”

“So that wasn’t a case of sitting in front of a piano and writing a song – that would be true for say Surrender on Tomorrow Never Dies. My starting point was: whenever I saw a James Bond it was always the song that catches your ear first. And it’s usually the thing you hear before you see the film – it’s out in the world before the film, so in a way it’s a big invitation to see the movie. So when I was asked to do Tomorrow Never Dies I thought: ‘I want to write a Bond song’ and that was literally at a piano trying to think what a Bond song could be for this film.”

Again, was this a situation where you preferred to work on your own, or did you collaborate?

“I like to come up with ideas on my own first and then share them, because I hate going into the room for a songwriting session. To be perfectly honest I don’t think I’m good enough to sit down and come up with something great immediately. I don’t want to waste anyone’s time, least of all my own. But when you’re in a room with someone, as a writer – whether it’s an artist or a co-writer – everyone wants to be good and everyone wants to have great ideas, but sometimes you really have to dig deep and find it somewhere and it’s not always there. So I like to come up with something first and then look for collaborators to further the idea. With songwriting, I’m not the sort of person that would topline a song – I’m not saying I couldn’t do it, I’ve never tried – but I couldn’t make a track that someone else would write a tune for, because I think the two go hand in hand.”

What was the collaborative process for a song like You Know My Name with Chris Cornell?

“It’s interesting because I knew I was doing Casino Royale before we knew who was going to be involved in the song. It was one of those things where I wanted to write something new for the new Bond. I had a bunch of ideas that I’d been playing around with on the piano, and then we found out we could work with Chris and he was up for doing it. He came down to the Casino Royale set in Prague, had a meeting and we both said we’d got some bits and pieces. So we agreed to go away, work on the ideas and meet again three or four weeks later. When we met again, in his apartment in Paris, we played the stuff to each other and found we’d kind of written two halves of the same song, which is really spooky.”

What state were those initial ideas in?

“They were chord sequences, melodies, and nascent lyrical ideas. We’d both come up with a very similar approach to it and it was all glued together and refined between the two of us, over the next few weeks. That was an easy process because Chris is brilliant and a lovely person, but we also had the same take on what we were doing.”

How about with The World Is Not Enough, when you worked with Don Black?

“That was easy because Don is a genius! He has a way of writing a lyric which, on paper, you might not think is particularly ground-breaking, but when you sing it you realize it ‘hugs’ the contours of the singer’s mouth. That’s a very special thing – Don has a way of writing a lyric that has a conversational style. What I asked Don for was lyrical ideas based on the start of an idea, and I’d write something whilst looking at his lyrics.”

Is that because you were in different parts of the world and couldn’t meet up?

“No, we were both in London at the time, but I think it’s a case of wanting to make mistakes privately.”

You’ve written the music for five James Bond movies, so far. Does it get easier each time, or harder as you try to do something different each time?

“It becomes slightly more difficult, only because your initial response to the first one has probably used up all your brightest ideas perhaps that you had, and the ones that were most appropriate. Once you’ve exhausted that, you have to go back to it and thinking of other ways of basically doing the same thing. I think that’s a challenge with Bond – when you do more than one, and you’re trying to push things along a bit – is how do you make it different, but somehow be the same?”

[cc_blockquote_right] I STARTED OUT PLAYING PUBS AND CLUBS…I RECEDED INTO THE COMPOSITIONAL CAVE SOME YEARS LATER [/cc_blockquote_right]Are there constraints to writing a James Bond theme?

No, I don’t think there are. If you look at the history of the songs, how different they’ve been – from You Only Live Twice to Goldfinger, or Live And Let Die to The Spy Who Loved Me, and Goldeneye. They have a core DNA of Bond about them, but if you think about them as songs, they’re all very different.

How about with the score?

“The composer’s free to do whatever we want, to a certain extent, but the shadow of John Barry looms very large over the entire thing, just in terms of the heart of it. He created the sound of James Bond, musically, and pretty much every composer that’s worked on the films has been very aware of that and we collectively dock our hats to acknowledge his creative genius. Eric Serra with Goldeneye was as far away as it got from the sound of John Barry, but I still think the spirit of the character he created in music was in the Goldeneye score as much as in any of the others.”

How do you feel about the prospect of performing on stage for the upcoming A Life In Song concerts, when you’re so used to creating in private?

“Well, I started out playing pubs and clubs, and I receded into the compositional cave some years later, when I realised I was never going to say ‘thank you Wembley, goodnight!’ But at the beginning, I played a couple of times a week around Bedfordshire.”

What did you play?

“Guitar, piano and I’d sing. It was just a three-piece function band and we’d play hotel restaurants and working men’s club for three or four hours. It meant covering an awful lot of music and different styles. Also, people didn’t necessarily want you there and could get a bit ugly. Sometimes it was fun and sometimes it was dull, but I never really had a problem with dealing with people from the stage, so I feel reasonably confident about that. I don’t think I’m anything to write home about, particularly, but I like doing it and we’ve got a reasonable catalogue now to hopefully make it an interesting night out for people.

“I mean, we are ‘behind the scenes’ people, so the job is inherently anonymous, and quite rightly so – it’s not about ‘you’, it’s about the film. So it’s a bit of a peculiar thing when you try to do shows, because here’s someone who you’ve probably never heard of, but I think people will come because they like the films and the music in it. It’s an opportunity for me to reclaim the songs for music, rather than it just being part of the soundtrack, tell some stories and chat about what it’s like, what we do and who we meet – there’s nothing salacious…sadly! The idea is to turn a concert hall into your front room.”

So what’s next? Do you still hold any burning ambitions or is it a case of seeing where the work takes you?

“I’ve always said I’d like to make a record, but I’ve said that every year for the past 25 years, and I’ve never done it, so it obviously means I can’t want to that much. I’m just starting a Sherlock Christmas special, I’m doing a show for ITV, which is a recreation of Jekyl & Hyde, and I’m doing a film which should be finished by the end of May, all being well. And I might start writing another musical, as that’s one of the favourite things I’ve done in my entire life.”

What would you say to any budding film composers and movie songwriters out there, who might like to follow in your footsteps?

“The revolution in technology has completely changed the landscape in which we’re working and the means by which you got into the industry in the early days is very different to how it happens now. Someone like Hans Zimmer effectively takes apprentices and he has a facility where people can learn how to write film scores or make the amazing sounds he comes up with. That’s a very generous and effective way of doing it. Other people would be a composer’s assistant and make their way into a couple of co-writes that way.

“It’s all about meeting people and finding your own voice and proving yourself to be a team player and someone who people like. The main thing to be in this industry is to be a nice person and someone who solves problems. I still think the best thing you can do, if you want to be a film composer, is to compose music for a film. Even if you haven’t got any professional experience, you need to be able to be able to turn up with something – that’s the evidence that you’re committed to what you say you’re going to do. With the technology today, it’s so much easier to actually have a ton of great sounding work.”

Interview: Aaron Slater

Following the huge success of his Royal Festival Hall Show in London last year, David Arnold confirmed three new dates for his 2015 UK tour: London Barbican Centre on 18 June, Birmingham Symphony Hall on 26 June and Nottingham Royal Concert Hall on 28 June. These join the existing show at the Manchester Bridgewater Hall on 14 April. Ticket prices vary, so to find out more, visit www.ticketmaster.co.uk

That was a very down to earth and non-pretentious article. And informative. It was nice to read about his background, his strong points and weak points. He comes across as a really interesting bloke! Nicely written article