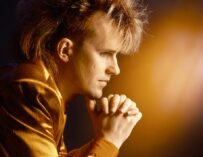

D:Ream’s Peter Cunnah and Al Mackenzie. Peter: “I was sitting in front of this girl and she said, ‘You know what they say, Pete? Cheer up, things can only get better.’”

The duo reveal the evolution of their 90s chart-topper from a Stonesy guitar riff to euphoric piano and brass-driven dance-pop

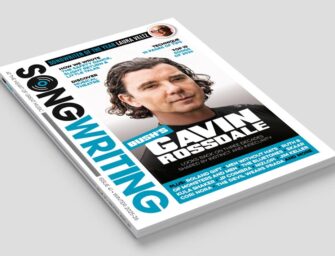

D:Ream, the dynamic duo comprising Peter Cunnah and Al Mackenzie, etched their name into the annals of 90s dance-pop history with a string of infectious hits. Formed in 1992, the British group seamlessly blended soulful vocals with pulsating beats, creating a signature sound that defined the euphoric spirit of the decade.

The duo’s breakthrough came in 1993 with their debut album, D:Ream on Volume 1. However, it was the chart-topping single Things Can Only Get Better that catapulted them to international acclaim. The track’s success transcended the dance floor, hitting the UK Singles Chart on no fewer than three occasions, and achieved iconic status as the unofficial anthem for the Labour Party’s victorious 1997 election campaign.

Although their new hits collection D:Ream: The Best Thing proves the band were far from a one-hit wonder, we asked Peter and Al to turn the clock back 30 years and reflect on how they made a song that was the making of them, and become synonymous with the era’s energetic optimism…

Released: 18 January 1993

Artist: D:Ream

Label: Magnet/FXU

Songwriters: Peter Cunnah, Jamie Petrie

Producers: D:Ream, Tom Frederikse

UK chart position: 1

US chart position: –

Peter Cunnah: “I started working with a guy called Jamie Petrie who was the co-writer and we started a band called Jordan at the same time there were all these double acts coming out, like Wham! It was interesting, because when he came to me with the original version it was more like a [Rolling Stones] Sympathy For The Devil thing. That’s what we had, we didn’t have the chorus, but it had that feel, you know? He brought it back because his son was just born and he had the set of words, ‘You can walk my path, you can wear my shoes / Learn to talk like me and be an angel too.’ And we thought this was great but we didn’t have a chorus.

“At the time, I was working in a place like [the setting of] Ricky Gervais’ The Office, where lots of intellectual people were being very bored, sharing the same space, and entertaining themselves by taking the piss out of me! And one day, someone in the office said something that I found quite hurtful and I was a bit teary, and I was sitting in front of this girl and she said, ‘You know what they say, Pete? Cheer up, things can only get better.’ I had a Sony Walkman back then and I ran straight into the toilet and recorded it. Then at the weekend I was working with Jamie and we married those two things up and it just really worked, it was great. We had that ‘You can walk my path…’ sort of Sympathy For The Devil thing and then we have the chorus being sung over those chords.

“So that was incarnation number one, if you like, which would have been in 1990. And then Jamie and I didn’t work out – he had a second kid and the pressure was on. I mean, I can’t remember who said it, but they say ‘the enemy of creativity is a pram in the hallway!’ And it’s true because if you’re between 16 and 21, you get that window, and if you get to 21 years old and there’s prams appearing and mortgages and responsibility, the pressure you feel is massive. Anyway, fast forward to when Alan and I met…”

Al Mackenzie: “When I met Peter he was in a band called Baby June and we did a remix of Hey! What’s Your Name. We experimented with a lot of brass sounds and stuff like that, so we’d just done that and moved on to the next track, and were working on this instrumental with lots of brass. And Pete cleverly thought, ‘Oh hello…’”

PC: “I had a light bulb moment and I started singing the chorus [to Things Can Only Get Better] over it. But without putting any vocals on, we just took that instrumental and played that out first. We went down to Maximus’ Love Ranch [a legendary night at the London club] because Alan had a residency there and my God, we played it at the end of the night, the lights went on and everyone went absolutely mental… and that was just the instrumental!”

AM: “When we got signed, we’d already planned to put out a four-track EP [4 Things 2 Come] which had four instrumental tracks, essentially. So they let us put it out and we sold loads of them. I remember taking a box of 25 of them into a record shop off Kensington and they went, just like that, and I had to bring some more down. Those were the good old days when you could sell vinyl just like that. It was mad, really.”

PC: “What’s interesting there is… When I was in [the Belfast-based band] Tie The Boy, we spent all our time running around trying to get demos to the heads of labels and A&R departments, and I turned my back on that. Then when I was working with Alan in the club scene, we were just making records to make people dance and that’s totally different. So when we had that song sitting in the background, we thought we could bring more elements into it.”

AM: “And the instrumental was in a different key wasn’t it?”

PC: “Oh it was all totally different to how it turned out. It took maybe two years before the version that you know actually took shape. Because, mainly, it’s really hard to get a kick drum and bass sound big enough to move the speakers. We had to meet the right engineer to do that and be in the right studios.”

D:Ream’s Peter Cunnah and Al Mackenzie. Al: “I was absolutely convinced by the song. I’ve always thought it would be a number one.”

AM: “When we got together you started rewriting the verses and stuff.”

PC: “We actually had the record ready to go and the biggest problem we had with it was it didn’t have the chorus if I just sang ‘Things are gonna get better’ on it – it was really weedy because it was just one voice. So the first time we tried it, I got all my mates and we all sang it and it was bloody rubbish. Then we ended up getting some professional girls in, with four of them and we triple-tracked them, and that wasn’t working. I was pulling my hair out at this stage. Within about a year, we’d gone in for one last time to see if we can make this damn thing work, and we’ve got a whole load of other singers and we track the hell out of them. Then I’m sitting in the control room with our engineer Tom Frederikse, the producer, and he brings up the first session I did [on my own], and puts up the second one, and then he puts up the third session…and all these voices turned from one to 60! And that’s the sound. But we didn’t know what we were looking for, until we got it.

“Brian Cox was driving us around as our tour manager before we got him into the band – he was a useless tour manager, but a great piano player! So I was sitting in Brian’s Volvo estate and we’re piling down the road and I was trying to write [the lyrics] while the lights on the motorway were going on and off, and then on, and then off… So that’s why I have the distance between the words! I thought, I’ll leave that distance in there, because it allows the listener a bit of time to digest the words. You know, I’m not rap star for good reason! So it’s just that economy of wording…And I re-wrote both verses myself. Then we wrote this whole new thing at the front, which was over the old piano. And the first time we put the record out, they cut out the ballad bit at the front because it was just a minute-worth of piano and vocal.”

AM: “They just cut it. I walked into Warner’s and they said, ‘Here’s your radio edit.’ It was mental!”

D:Ream’s Peter Cunnah and Al Mackenzie. Peter: “We didn’t know what we were looking for, until we got it.”

PC: “So about a year later, when we released it, they reinstated that bit. And as Tom Frederikse always said, ‘Everyone thinks this is a ballad, and then it comes in and it’s off!’ And that was it. So the dynamics between writing the song and writing the record, we don’t separate them – we work on the record and we work on the lyrics and they kind of feed off each other. Yeah okay, it’s great to sit down with your guitar and piano and write something, that’s lovely, but if you’re making contemporary records, I think they’re both one and the same.”

AM: “I’ve always said this, I was absolutely convinced by the song. I’ve always thought it would be a number one, I don’t know why. I just had a feeling it had something about it. For me, personally, anyway…”

PC: “I work at all of them as hard as I can and I strive to make them where I’m past my limits and they’ve challenged me. Like I don’t think any guitar player is ever happy with their level of playing, they’re always looking over the shoulder and as a writer, you’re like, ‘Have I written this the best I can?’ I often used to say to myself, ‘Well, if you think that’s a chorus, why don’t you just make that the verse and then go for another chorus?’”

![Interview: Jessie Jo Dillon [2025]](https://www.songwritingmagazine.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/jessie-jo-dillon-2-by-libby-danforth-335x256.jpg)

Related Articles