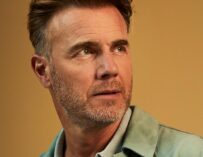

In 2022, with a triumphant new solo album under his belt, the unassuming Take That megastar finally embraced his calling

Editor’s Note: Originally published in Songwriting Magazine Autumn 2022 – republished to coincide with the 2026 Take That Netflix documentary

You may think that 12 UK No 1 singles, 8 UK No 1 albums, and over 45 million records sold with Take That would pave the way to a gilded ego – especially when you’ve been a key part of the group’s songwriting since their triumphant return in 2006 – but Mark Owen remains modest to a fault, especially when discussing his own songwriting. Though part of his appeal, his contribution to both his band’s success and own output as a solo artist demand something of a reappraisal.

That solo career started with his 1996 debut, Green Man. Propelled by singles such as Clementine and I Am What I Am, to revisit it now is to enjoy something of a pocket Britpop rocket. Subsequent albums, In Your Own Time, How The Mighty Fall, and The Art Of Doing Nothing, track the evolution of an artist who successfully straddles the indie and the mainstream. His newly released fifth album, Land Of Dreams, is packed with jubilant pop music with a positive message. His highest charting solo record to date, it plays to Owen’s strengths as an artist and songwriter, and should finally put any doubts he has about his own ability to bed.

It’s been a long road to get here, as we found out…

First published in Songwriting Magazine Autumn 2022

What can you tell us about your early experiences of music?

“I didn’t do music at school, but I listened to so much music, and the first person that I loved was Elvis Presley. My dad played guitar in a lot of bands, including one called The Exiles. He played guitar around our house all the time. He was the lead guitarist in a band, and they had a lead singer, and they ended up doing a lot of Irish country music. My upbringing, on a Friday and Saturday night, was falling asleep underneath the table at a gig that my dad was playing.

“So I watched my dad, and he’d sing one song, Johnny B. Goode, every weekend when the lead singer took a break. That was my dad’s song that he’d sing every week. I knew that we were halfway through the evening when he’d sing that.”

Was that always with The Exiles?

“The band he ended up in were called Johnny Loughrey & The Countrysiders, but the band that I mainly remember when I was very young were The Exiles, and he used to have this purple suit on. I remember him leaving the house with his guitar case every week, and he loved it. He loved guitar all his life, and still does, it’s a proper passion. It was his world and still is.”

But it was a while after that you started writing yourself?

“The first keyboard I ever bought was off Gary [Barlow]. And it was a [Korg] O1/WFD and it was with Cubase; I bought a computer and a keyboard off Gaz, when we first started off in the band after a couple of years. Then I started to try to learn how to use that and I started to learn chords. I still write more on piano than I do on guitar. I love guitar and I wish I played guitar 10x more than I do. I play guitar on stage when I get the opportunity, but I write on piano. One of the first purchases I ever bought was, when I bought a flat I also bought a Schimmel piano. That piano was what I wrote my first record, Green Man, on.”

So, going from writing your first songs to putting out that first album was quite a quick process?

“Yes, probably two or three years. I found it easier to write on piano than I did on Cubase. That was confusing for me. I couldn’t quite get my head around it. The electronic world was more confusing than sitting at a piano and playing some chords, and I just tried to do it by ear.

“I was very lucky that I had two producers involved in that record, John Leckie, and Craig Leon. John had done Radiohead’s The Bends, and The Stone Roses by The Stone Roses, two of the records that I adored. The Stone Roses were the first band that I got into. So I went from Elvis, to Madonna, to the Stone Roses, to Nirvana, to a keyboard, to a piano. Ever since then, I’ve wished I could play guitar much better. I do wish that I had studied music at school.”

And you’ve constantly written since that point?

“It’s been a real process for me, the whole songwriting thing. My relationship with it has been a real journey. I remember I was in New York, and I was sat with Gaz in Clive Davis’ office. He was like the boss of the music world, I don’t know why I was at this meeting because I wasn’t really writing songs back then, but I remember sitting in the room and he played me a song by Whitney Houston.

“I was a bit of a spectator as he talked about the relationship between the lyric and the song. I remember him talking quite a bit about Whitney and these songs and I remember going, ‘I think I know what he means.’ It made me want to go and try and write songs. Before then, I’d thought Gary was the songwriter and wrote the songs in the band.”

Do you know when that was?

“I don’t know how old I was then, maybe 18/19. I wasn’t looking to progress, I was still spinning on my head [breakdancing]. But I came out there going, ‘I really want to try.’ It inspired me enough to make me want to write songs. Which is a little bit weird, really, when I when I think about it. Also Gaz, he was a big inspiration. And the people around, the bands I was listening to.

“The Stone Roses I was probably more enjoying what was going on and the way it made me feel musically. With Radiohead and The Bends, that was a time when I started to get a little bit of a thing… I started to hear a lyric that made me go, ‘Oh, what does that mean?’ Songs like High And Dry and Fake Plastic Trees. They are the songs that were really resonating with me.”

Mark Owen in Songwriting Magazine: “If a vision starts coming, I’m onto something.”

Why do you think they resonated so much?

“[Thom Yorke] was singing in falsetto and he was doing something a little bit different; he wasn’t a traditional singer in this way that you had to do it. There were different things I was hearing: different styles and different ways of expression. Songs don’t all have to be done in the same way. That was quite an interesting thing for me to start looking at.

“It was definitely resonating; things were hitting me in different places than they had been before. So they were big parts of the journey that I was on. They then became the reason that I wanted to work with John Leckie but I was coming out of a band like Take That and I hadn’t really written.”

You must have been doing something right for John Leckie to want to work with you?

“When we’d finished Take That I came out and I sat at that piano and I wrote about 35 songs. So basic in production, and in sound, literally piano and voice. I might have attempted to put a drumbeat on some of them, but very rarely, because I realised that wasn’t serving me.

“I managed to get that cassette tape to John Leckie, it was probably through a label and I would have said, ‘I’d like to work with this person.’ He was the only real producer that I knew, outside of the Take That world, and he’d made two of my favourite records. Amazingly, he said yes. He tells me a story that he went and asked his neighbour, first of all who I was but then who Take That were. But he said yes, and he brought Craig in and they brought in musicians that were incredible.”

Can you remember any examples?

“I had Clem Burke from Blondie on drums, just brilliant people, and I was at Abbey Road bloody Studios! So, I was making a record at Abbey Road Studios. I was crossing that zebra crossing every day with John Leckie and Craig Leon and it was the most amazing time. I was living at Abbey Road, staying in a flat next door. I was sleeping there and got to know all the staff. I never left and soaked it all up. I was so excited and everybody came to visit me at certain times. Rob came, Gary came, Howard came, Jay came.

“They all came and I was playing all the songs that I’d done and I was just so excited about the whole thing. It was in the days when it was on tape, so John Leckie was cutting tape and sticking it back together. It was brilliant and I’ve never seen that since.”

It sounds like George Martin-esque magic?

“It really was and it was a brilliant time. But also, I played my first ever solo gig at Abbey Road in Studio One but I was trying to catch up to where I wanted to be. I then needed to go away and have the other side, where I’m sat with the songs and can’t get anybody to listen to any of them, which came later on down the line.”

That must have been frustrating, especially as you were a more experienced songwriter by that point?

“Yes and then all things start happening and you start thinking about it. The process then is an ongoing one, I guess, which has these wondrous peaks and then these moments where you think, ‘Do I have any idea what I’m doing?’ Eventually, I reached the point where I said, ‘I’m never going to write a song again,’ and I gave up a little bit on music. I don’t know when this was, maybe early 2000s.

“I had fallen out of love and my ability and belief had gone completely the other way. You doubt yourself. I was in a different stage of life where I was lost and not sure what I was doing. I wasn’t sure what the future looked like. I had a real period off; I went about six months without listening to music. I’d walk past that bloody piano every day, never touching it, but I saw it sitting there looking at me. So yeah, it was a funny time.”

Did something happen to trigger a resurgence?

“The album was How The Mighty Fall. I decided, ‘You know what, I’m just gonna write an album, ten songs.’ So I did it on my own label, these 10 songs. I’m trying to think of what that main spark might have been for me to want to write again…

“It might actually have been a friend of mine who got me back doing it, because I think he came to see me and said, ‘What are you’re doing?’ We talked about it and and then I’ve made this decision. I think he talked to me about doing it on my own label – I could do it at my house and I could make a thing of it.

“So I started to write these four chords, which became the first song They Do. And I said, ‘Well, I’m gonna write an album of 10 songs in the order that they come out of me and then that’s my goodbye.’ I didn’t know whether that was my goodbye but I think I wanted to see whether I could do it.”

Was making that album an enjoyable process?

“I sent the demos of those songs to a guy called Tony Hoffer, who’d produced Beck and Air. I told him that I’d got no label and was doing it with my own money. He said he knew immediately that he’d like to do the record. So I went out to LA to make the record with this guy that I’d not met in his studio at Sunset Sound. We worked on this record, and Beck’s dad did the string arrangements for me, and one of the keyboard players on that record was Greg Kirsten, which was awesome.

Mark Owen in Songwriting Magazine: “All of a sudden I’m not the new kid on the block.”

“So the record got signed, eventually, to a German label. And then I did a tour of little German record stores and it was brilliant. I loved it. Then a tour of Europe on my own label, with my own record, coming out of Germany, and I really enjoyed that process. I really enjoyed getting back into it and then bloody Take That got back together and ruined everything with their gigantic bloody success (laughs)!

“That was a long way for me to get back to the band, but when the band came back together, I still wasn’t a confident songwriter, I still hadn’t naturally found a place where I felt people would want to hear the songs that I was writing. I felt a little bit like I was still learning, which I guess you always are, even though I’d done quite a few records by then. I hadn’t settled into that profession.”

And if someone said to you now, ‘Nice to meet you, what do you do?’ Would you say, ‘I’m a songwriter’?

“Well, a big point for me is when people ask for your profession on forms. And to be able to put “songwriter” was a big thing. That took a really long time to be able to put that, for me personally, which is the most bizarre thing because I could have put it even when I wasn’t one, because nobody ever reads it.”

When you were starting Land Of Dreams, did you now come at it from a position of confidence?

“Again, it’s been a process for me. Going back in the room with Take That was a big thing for me, being able to have that sort of writing tool when Take That came back was massive. I think for the band, the second time round, it’s apparent that a lot of the songs came out of that world that I had been a part of, and had been building and learning.

“I think it helped the band as well in many ways, because we were able to write in a different way and bring some different elements into the music. So that’s been a wonderful experience. Probably since How The Mighty Fall, all my attention has gone to writing songs for the band. So that’s what I did”

It seems like such an interesting cycle… Your solo career feeds into your work with Take That, and then that helps with your solo work. Is that how you see it?

“Yeah, and probably more than ever, I took everything that I had learned and put it into this new record. This album comes from falling asleep under a table listening to my dad playing guitar, from watching Gary in the studio, being in a room with Rob, being in a room with Clive Davis, being there with John Leckie, working with Greg Kirsten… all those elements. I actually went, ‘Oh my God. I’ve got all this experience.’ All of a sudden, I’m not the new kid on the block.

“It was really weird going back to Greg, when he did These Days and a few tracks on that record [Take That’s III]. Then I saw Greg with Paul McCartney about three years ago in Henson Studios in Los Angeles. I was in the booth doing some singing and Greg and Paul came in. I remember when I saw Paul, I thought to myself, ‘Oh my God, it’s Paul McCartney. Sing your effing arse off, right now.’ When I came out I said to Paul, ‘I taught him everything he knows,’ because Greg was doing McCartney’s record. And then I said to Paul, ‘But you taught us all everything we know.’

“And wasn’t it amazing seeing him at Glastonbury this year? I was so pleased for him, and for British music and world music and music in general. I think it was a real celebration of music and then you have people like Billie Eilish, who I’ve seen a couple of times in the last year, and FINNEAS… amazing songwriters, I taught them nothing that they know!”

Do you still get inspired by new music?

“Absolutely. I think Billie and FINNEAS are stunning songwriters. And Kendrick [Lamar], who was playing on the Sunday, is also a stunning songwriter. I now love music more than I’ve ever loved it. I fell out of love with it for a little bit, but I’ve fallen back in love with it. I really love writing, being a part of the process, and hearing new artists, old artists, learning new songs, Shazamming something in a restaurant, trying to find out who sings it. It’s a beautiful process. I still probably don’t have a clue, but I do write “songwriter” in the box now. That’s a good thing. But I put “songwriter/breakdancer”.

Let’s finish by talking a bit more about the new album. What can you tell us about the process of making it?

“It was a wonderful process and I loved making this record with Jennifer Decilveo who produced it. Producers are a really big thing for artists, and songwriters. Jennifer on this record, plus Harrison [Kipner] and Stefan [Mac] for completely different reasons, was massively inspiring.

“Jen came first and we did Rio together, which then gave me the vision. It started to give me a colour for the record, which was really important. Once I’d got the colour and started to see a picture there… a lot of the time I probably think in pictures and visuals and I always know that if a vision starts coming I’m onto something.”

What does that look like?

“The story starts forming, or characters start forming within it, or I start to see the subject matter. Things are happening that start to play with reality. I guess a lot of that stuff is like the land of dreams, where reality starts changing, like in those old Beatles animations. So you’re sat in the room with these various people that are in your songs and they’re helping you write the song, it’s like they’re sat on the chair as you write.

“Other people start to come up and appear; people who I’ve met that have been an inspiration at certain points start to come into the room and get involved. That’s really exciting. It’s a wonderful world to be a part of, and I love going into it. When you go into those places, and you’re in those things, it’s great. Then the next day you sit down and nobody turns up, and you think, ‘Right, that’s it? It’s all over.’”

Related Articles