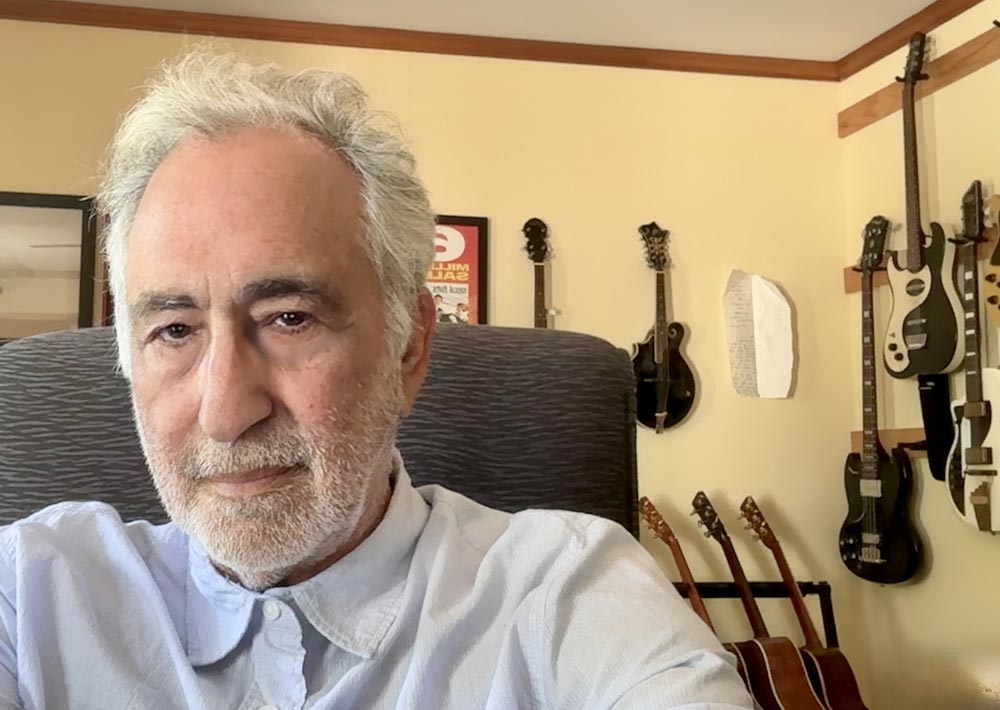

Eddie Schwartz: “It’s like anything else, the more you do it, the more ideas come in.”

We chat with the hit songwriter who’s rediscovered his creative voice and love of making music after a lengthy drought

Eddie Schwartz is a Canadian songwriter, producer, recording artist, and advocate with a career stretching back over 50 years. His songs have been recorded by Pat Benatar, Carly Simon, Paul Carrack, The Doobie Brothers, America, and more, producing hits such as Hit Me With Your Best Shot, Don’t Shed a Tear, and Special Girl. As a recording artist, he released four albums, while his songwriting alone accounts for physical sales of over 65 million units worldwide.

Beyond the studio, Schwartz has championed creators’ rights, serving as president of the International Council of Music Creators and Music Creators North America, and was appointed a Member of the Order of Canada. His career, recognised by JUNO, BMI, and SOCAN awards, is equal parts artistic achievement and dedication to supporting his fellow songwriters and musicians.

After years of writer’s block, Schwartz recently found a renewed voice in the turbulence of the contemporary world. The result is the six-track EP Film School, a considerately crafted collection of songs that move between reflection, imagination, and measured optimism. Film School represents more than Schwartz’s return to songwriting; it is a reclamation of confidence and a reminder that, even after creative silence, a songwriter can find renewed voice and purpose…

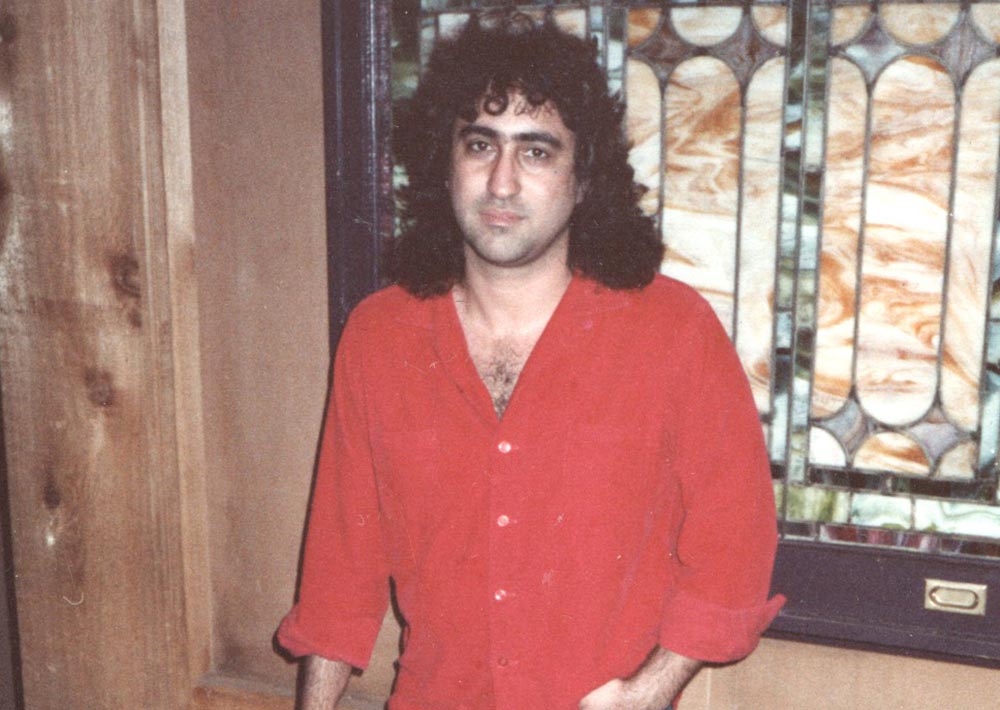

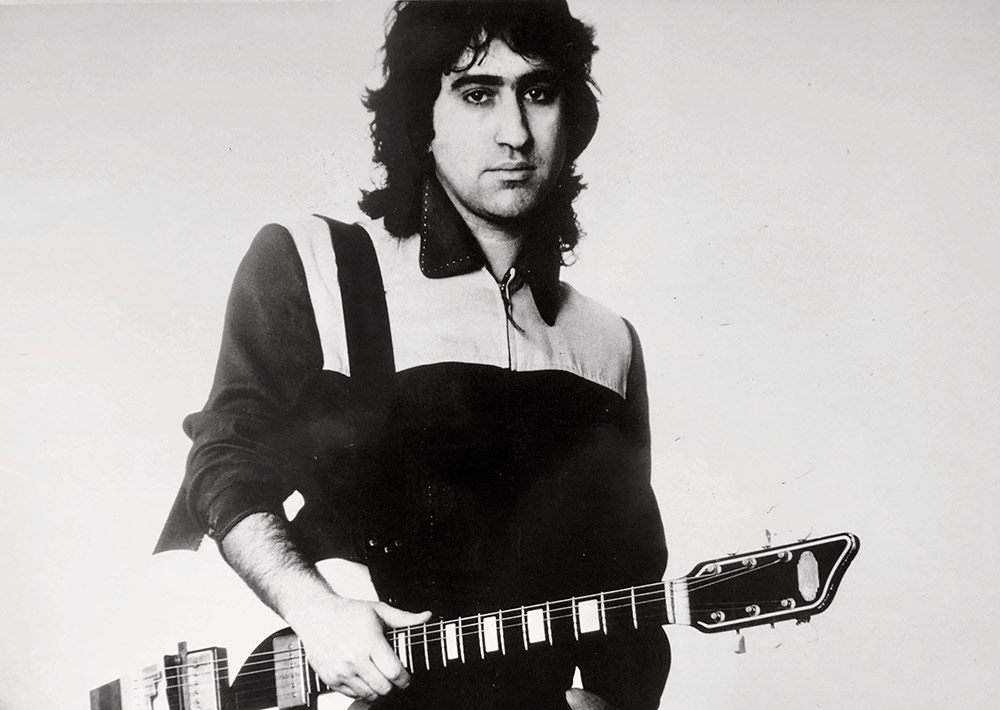

All photos: courtesy of Eddie Schwartz

Are you in Nashville today?

“I’m in Nashville, which is where I spend most of my time these days. We’ve been here since 1997. Every time I leave this room, it’s like, ‘Am I in the same city I was in the last time I drove around here?’ I mean, it’s just insane. It really has grown tremendously.”

Was it a case that you had a sudden dose of writer’s block that lasted for a long time, or had your interest and desire to write songs been on the wane for a while?

“I think you summed it up, it was sudden, and then it lasted for a long time. I moved to Nashville in ‘97 from Toronto, Canada. In my Canadian life as a songwriter, I took as long as it took to write a song: I revised, I rewrote, I put it away for a little while, I came back to it… I had a process that took some time, and a lot of patience. My philosophy was, the world doesn’t need another okay song or even another good song. I have to try to get to the top of the mountain creatively. I’m not talking about career-wise, because it was always about the work, about trying to write the best song I could.

“Then, I moved to Nashville. I had a couple of publishers who encouraged me to come down here. Things were changing in Toronto; most of the people that I worked with, did demos with, and was friends with – my peer group – left. Most of them moved to LA. I had a young family, and I didn’t want to go to LA. I very quickly got into the Nashville writing scene, which is… you write from 10 a.m. till 1 p.m., have an hour for lunch, and then you write from 2 p.m. to 5 p.m. every day, five days a week, very often with different people in the morning than in the afternoon. I did that for a number of years.”

Eddie Schwartz: “That’s the goal – to write something that, if you were around a campfire and just had an acoustic guitar, it would work.”

How did you find that way of working?

“I wrote with some incredibly talented people. I got some good cuts. Again, not that that was necessarily what I wanted, but, you know, it is the music business. But it wasn’t me, it wasn’t the way that I worked, and I didn’t feel like I was doing my best work.

“The songs were okay, but I didn’t love the songs, and so I stopped. I just quit doing it, and got very much involved with advocacy, and spent a lot of time and effort on that. Then, when I went back to write the way I had written previously, it was gone. The ideas… there were fragments floating around, but I didn’t know what to do with them. I couldn’t bring them home.

“So, the advocacy part of it… there’s always people who don’t want to pay artists and songwriters. It’s a tough world out there for people who make their make their living this way. I felt like I was doing something useful and I did a lot of global stuff. I worked with an organisation based in Paris, called CISAC, and the creator arm called CIAM. Music. I stepped down as president late 2024, so I knew I was going to have time. I went back to the drawing board after years of not doing it.”

What happened next?

“We Win was the breakthrough song. I had that title. I had some music, again, fragments had been kicking around for a while, and I just couldn’t find a lyric that I thought was really worth saying. Then, it was very much like a bolt out of the blue. I went and I sang it with the music, and went, ‘This door could be open a crack, can I sneak through?’

“That’s basically what happened. It was me reconnecting. You can never go back to the place you started, but you can go back to a place that’s parallel with it. It wasn’t exactly the way I wrote before, but it was a process that I could own, and really get myself into. So, We Win was the first song I finished leading up to Film School, which is the EP that came out recently.”

Do you have an explanation as to why that particular song brought the spark back?

“Not to take all the mystery away from creativity, because I usually feel like I’m stumbling around in a dark room. But, the political situation… people make reference to how difficult things are in the world these days. It seems like we’re in a period of chaos and negativity, and a lot of people go down the rabbit hole. Although I share a lot of those feelings, I was trying to resist going down the rabbit hole, getting lost in despondency.

“We Win was throwing myself a life draft: here’s a positive message, here’s something that’s good, here’s something that I should remind myself, remember, and celebrate – no matter what goes on out there in the world, each one of us, including me, can love and be caring and have that in their lives.”

Have you always been someone who’s processed the state of the world through song?

“Totally. People may know a song of mine called Hit Me With Your Best Shot, which brings to mind another song called Don’t Shed A Tear, done by a fellow countryman of yours, Paul Carrack, an amazing artist. Each one of those songs were really about moments in my life or realisations that I came to.

“Don’t Shed A Tear… I was in a breakup, dealing with that and trying to empower myself, shore myself up about the fact I was going to be okay and would get through it at that moment in time. So, the answer is, very much.

“I need to do this for myself, because it is a compulsion to write. It’s not something I feel I even have a choice in, but other people go through similar things and maybe this is a way that I can connect with people who are feeling what I’m feeling at this moment in time.”

Was it then that classic cliché that, after the first trickle of creativity, the floodgates opened? Or did you have to struggle again to write the rest of the EP?

“Outbound Train – I had most of it, but I didn’t have a bridge and that took a long time. Finally, I realised, ‘Okay, I think this is what the bridge should be.’ Again, I was stumbling around in the dark, saw a little crack of light and went, ‘Oh, let’s go this way.’ and see what happened.

“They all were very similar, in other words, formed from partially written ideas that I had. Once I’d written We Win, I went back to this group of ideas, and there’s still other ones floating around that I haven’t finished. I went back and thought, ‘I think I can finish these now,’ and in some cases, I was successful. Those are the songs that are on Film School.

“But Special Girl is a song that I put out myself in the ‘80s, so that’s a little different because it was already written. When I listened to the record, which I do on occasion, I felt it sounded so 80s and maybe I should do a simpler piano/vocal version, which I did. I want to thank Lou Pomanti, who’s the arrangement and a great keyboard player in Toronto. We worked on it together.”

We all say that a good song should still stand up with all the production stripped away, it must have been nice to realise that Special Girl could still shine through once you did that?

“That’s what you try to do, that’s the goal – to write something that, if you were around a campfire and just had an acoustic guitar, it would work. There are great tracks, some of my favourite music… I think of Under Pressure [Queen & David Bowie]. It’s a great track. I don’t know if it’s a very good song, but it’s a brilliant piece of music. I don’t mean to pick on them, but I just want to make that distinction. I want to do something that stands on its own, with very simple instrumentation.”

Eddie Schwartz: “When I went back to write the way I had written previously, it was gone.”

You use the metaphor of stumbling around in the dark… Are there things that you can do that are the equivalent of lighting little candles: times of the day, places, ways of working, that help it be slightly less dark?

“Once you get the momentum going… I think that’s the key, that breakthrough, in terms of We Win, is sparks. I don’t know if they’re candles or sparks, but if things start to fire then one thing leads to another. One song leads to another, because I’m putting time into the process, which means there’s an instrument in my hands when I’m doing it, or I’m sitting at a keyboard.

“Mostly I’m a guitar player, but I can bang out a few chords on the piano, and I write songs on it as well as the keyboard. But yeah, you stumble on things because now you’re inspired, you’re putting time in. It’s like anything else, the more you do it, the more ideas come in and, I like to think, the better you get as time goes on. So, there’s definitely some sparks. Now, I probably spend part of every day writing, seven days a week, whether my wife likes it or not – my Special Girl, by the way, that song was written about her back in the day.”

There is some really well-observed imagery in the lyrics. Things like the “funny yellow raincoat” on Water Rises, the “card player in the dining car” on Outbound Train and the “sign on the lawn” on You Don’t Belong…

“You know, there’s a lot of really weird lawn signs. I don’t know if you have them? The crazy thing in this part of the world is, people have stickers on their licence plates and lawn signs that deal with very important and personal issues. It bothers me that people think you can reduce the lives of all people down to a lawn sign that’s got a half a sentence on it. I think that deserves some comment, so I find a way to do so through my music and songs.

“The card player in the dining car… that song comes from a different place. I was a huge fan of a guy named Rod Serling who was a great Hollywood and TV writer. He wrote the original Planet Of The Apes and he was the writer and the show runner of The Twilight Zone. I think it was really my way of paying tribute to him, because I think of Outbound Train as a vignette, slightly fantasy, three-minute TV show.”

Eddie Schwartz: “My average song has ten pages of single-spaced words, which then get boiled down to one page, eventually.”

What can you tell us about your process when it comes to lyrics?

“You know when something’s right, when something feels like it belongs in a song, like it’s whole cloth, it’s of a piece. That means, first of all, you have to find out, okay, so what is this cloth? Is it grey? Is it flannel? Is it multicoloured? What are you creating here? Then, once you’ve made that decision, the search for me is, how do you find what all belongs together so that every sentence, every line, and all the music reinforces it?

“Each element should reinforce every other element, is what I’m trying to get at. The two lines that came last, the card player in the dining car, the young preacher… that was the part that I had the most trouble with. I had to rest it; I couldn’t find something that fit in until that finally arrived on the scene.

“I would say my average song has 10 pages of single-spaced words, which then get boiled down to one page, eventually. Yeah, that’s the process. When I fill a page with ideas, I’m over the moon. I’m really excited. Then I come back the next day and go, ‘I don’t think so,’ or have to massage it, change some of it, keep working on it – if it is heading in the right direction. Then, the other thing is, I’ve got a melody and I’ve got to figure out how this melody and these words are going to fit together. So even if the idea is right, I’ve got to figure out a way to boil it down to something that’ll fit into one line in a song.”

How do you then know when a song’s finished?

“It’s usually when I can’t stand it anymore and I’m sick to death of it. That’s one factor. Another factor is, when I do come back a week later, or three days later, or even the next day and I go, ‘I think this is working, I think it’s right.’ It’s a feeling and I go, ‘Even if it’s not right, I can’t do this anymore.’”

Now that you’ve got back to writing, and recorded the songs, put them out, is that the end game in itself? Is there anything else you hope for?

“I just hope people appreciate them. When I say that, I mean, if it’s ten people, if it’s anybody… I’ve learned from being in the music business my whole life, the smart move if you want to stay sane, is to keep your expectations as low as possible. So, my expectations are maybe somebody will like this, and if people do, that’s wonderful.”

And lastly, is there one song in your esteemed catalogue that you would hold up as the time where you absolutely nailed it – or maybe the song you’re proudest of?

“I am very proud of the songs on Film School, because I think there’s a maturity there and I feel that they’re up there, and so I’m very proud of them. Then, I’ve always been a huge Paul Carrack fan, long before I knew him and he cut my songs, so I think, Don’t Shed A Tear is one that I would pick, and I can’t deny Pat Benatar and Neil Giraldo, so Hit Me With Your Best Shot.”

Related Articles