Wilko Johnson is one of the most influential songwriters to pick up a guitar, and feature in the sign of a bar. Image by Quercusrobur1

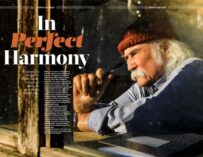

We caught up with a songwriting legend, one whose influence began over 40 years ago and is still felt today

I’m sitting across from someone who unexpectedly changed the course of music. The fast-paced songs he created in the 1970’s with Dr Feelgood, along with his guitar playing style, energy, attitude and stage persona, undeniably influenced the punk movement. Listen to She Does It Right; the riff, the simplicity, the drive – it’s three and a half minutes of proto-punk heaven.

Wilko Johnson. You might recognise his distinctive choppy guitar style, in which he simultaneously plays the lead and rhythm sections. However, if you’re not familiar with his music, the name will ring a bell following the terminal cancer diagnosis he received in 2012, and subsequent recovery. During this time, Johnson recorded and released an acclaimed album, Going Back Home, with Roger Daltrey. Since then he’s released an autobiography and is now preparing for his first headline show at the Royal Albert Hall (26 Sept).

We met with Wilko Johnson ahead of this show to discuss his songwriting process, recording philosophy and influences.

“This is actually a lunar telescope,” Wilko Johnson says, pointing to the large instrument near his window. “I haven’t really used it. I bought it before the cancer diagnosis. I like to look at the sun.” He gestures to the window, as rain drizzles down the pane. “You know, to check it’s still there.”

The last year or two has been busy for you: autobiography, release of your compilation I Keep It To Myself, tours and preparation for the Royal Albert Hall show. Do you think you’ll ever slow down or are you going to keep this pace up?

“Well, honestly I’ve kind of found I’m a miserable so and so actually and now, the only time I’m actually happy is when I’m playing. So yeah, you know, what else can you do? I was seventy this year and normally people have retired and that, I think. You know, you can’t retire really when you’re a musician. What do you do? Just stop doing gigs and everyone forgets about you. I don’t know. But yeah, just carry on really. I like it. We’re gonna be making an album. We’re doing the Albert Hall, then we’re going to Japan and then we’re probably going to make an album.”

New songs?

“Yeah yeah. I’m going through all that nightmare!”

What is your songwriting process? Do you write the riffs first?

“Yeah. Generally speaking, always. Absolutely, when I think about it, yeah. It’s usually like I mean. Everything I do is very simple. You know, I’ve never written anything that could be described in any way as complicated.”

I don’t know actually. I recently listened to Dr Dupree…

“That is an odd one actually. That one, again, it did actually start with the riff right. And then the melody comes out of the riff. So I’ve got this melody. And it’s actually in a minor key. And it’s got quite a wistful tune. And this is back in the Dr Feelgood times. I couldn’t write anything around this thing that Lee Brilleaux [Dr Feelgood singer] could’ve done. It just wasn’t his line of country. But I had this song when we went in to do what proved to be my final album with them, Sneakin’ Suspicion.

“And anyway the band broke up and so I had this tune. And I asked my friend – Hugo Williams, the poet – to see if he could make anything of it. And this was all in the aftermath of Dr Feelgood breaking up. We was sitting talking about this thing, Hugo said he had once written a song – or tried to write a song – called Dr Dupree. And I went “Wow! that sounds great!” And I thought of a line from Milton: “Dr Dupree and his Memphian chivalry.” You see the kind of way we’re going. Anyway, that didn’t proceed any further. But we had Dr Dupree.

“Then Hugo I think wrote the first two verses. And there’s all this stuff about somebody crashing in flames, really. And then I wrote the final verse which is about suicide, I think. In fact, I was trying to write this thing and I was actually in the vocal booth doing the vocal, and I’ve still got the last couple of lines. And I go, “sorry messed up. Got to start again!” and I actually finished it off there. And I think, it’s about all that. And it’s about……I don’t know. Being famous and then crashing down in flames.

“It becomes more publicity or more stories, and what. I imagine myself over in Canvey Island there’s these flatlands, and if you look westwards you see – or you used to, the oil refinery’s have gone now – the sun going down by the refineries. If ever I think about committing suicide, I was always think it’s going to be over there. I’m going to go over there, sit down and watch the sun go down and then…..I don’t know hara-kiri? This is just an image. As I say, the whole thing came together.”

You mentioned Lee Brilleaux, has your songwriting method changed from writing songs for Lee to sing, to now writing songs that you’ll sing?

“Well, when I used to write songs for Dr Feelgood I would have his voice in my head. And that’s how I’m hearing it. So if I’ve got a riff in my head I’m hearing his voice. Yeah, it kind of helped, you know to do this. Having his voice in my mind there was something to base the whole thing round. And of course, that went…I don’t know, with my vocals I can do more monotonous things.”

You recorded your album with Roger Daltrey, Going Back Home, in just over a week. A short recording session – say a week to two weeks – is that your preferred time to spend in the studio. I know it took a bit longer recording with Ian Dury and the Blockheads….

“Well, that’s the way it always worked. First of all with Dr Feelgood. Back then, it would take a couple of weeks. Maybe an extra week for this and that. That sort of time frame. Yeah, I like that best. I do like that best. When Ian Dury asked me to join the Blockheads, in the early summer I think, whatever year it was. I went to see Ian, and he saying, “right, we’re making this album,” he’s saying, “and we’ve got until October.” And I thought “what!”, I couldn’t believe it, man. It was a little bit chaotic making that album [Laughter], because there wasn’t really a producer.

“I mean Chaz Jankel had left the band and he really used to produce them, I think. I don’t know. But everybody was having a bash. And it was chaotic. And yes, it took a long time. I don’t really like that. Because if you’ve got the studio and you’ve got the opportunity to sit there and think “oh we’ll do this better, we’ll do that better” in the end you’ll smooth it right out until there’s nothing left at all.”

After your album you recorded with Roger Daltrey, Going Back Home, are there any other dream collaborations – past or present?

“I don’t know really. Someone asked me this recently. I said, I’d really love just once, to play with Bob Dylan. I wouldn’t try and write or anything. But you know, if we had my band and recorded a track with him – would I love that!”

What do you think of Bob Dylan’s newer albums? Again, those albums are recorded live with no real overdubs…

“Yeah, I must admit I’m an old hippy. I love Blonde On Blonde and Highway 61 Revisited. That’s really my favourite.”

You were spotted at Leigh Folk Festival listening to Martin Carthy. Being a hippy as well, I just wondered if you’d ever played the acoustic?

“I tell you something, I have never owned an acoustic guitar. No, I’ve never played an acoustic guitar or anything like that. But I’m a dedicated fan of Martin Carthy.”

What’s your favourite song to play live?

“I do like Dr Dupree actually. We usually do that once the sets got going. And it’s like “oh, a little bit serious!”. I like doing that, and I don’t know. Different nights you get off on different songs, you know.”

“I love poetry and all sorts of poetry.” Image by Man Alive!

In preparation, have you done anything differently for the Albert Hall show?

“I’m going to make sure we’re all on our feet first [laughs]. No, no. Well, no it’s just a show. Great, the Albert Hall and all that. But I mean, we just want to put on a really good show, in the Albert Hall. Don’t expect anything experimental!”

What would you say your influences, outside of music, are? You were an English teacher. Is poetry an influence?

“Not really. People are always arguing about poetry and that. Bob Dylan and…songs are songs, and poetry is a different thing altogether. I love poetry and all sorts of poetry. From Anglo-Saxon up to….Hugo Williams, but it’s a different thing from songs. And I don’t think there’s any literary influences on my songs [does mock-professor voice] let me think! [laughs] No, I don’t think so!”

In Zoe Howe’s book Lee Brilleaux: Rock ‘n’ Roll Gentleman it seems that the breakdown of Dr Feelgood was partly down to the amount of pressure you had on your shoulders. You had a young family, and you were expected to write all of the songs. Lee seemed really creative and intelligent, but he didn’t seem to want to write

“I tell you man. Lee was a fantastic character, a very intelligent, witty guy. He could be very very funny. And all sorts of stuff like that. And really, a great musician. And you would think, ‘This is a guy who could write songs’. And I was always trying to get him to write songs. I didn’t want it all me. They didn’t understand the kind of pressure….I mean, when you start out a band, it’s all fun and that. Then you do an album. Then you do another album. Then it starts getting freaky. They didn’t know about all that.

“I remember when I wrote Back In The Night – I sat up all night writing that fucker – and I was so chuffed with it, and I went to the rehearsal the next day and played it to them and they just sneered at it. Well, they didn’t sneer. They just went, ‘Oh, it’s alright’. You know, ‘You bastards, it’s really good!

“In the argument that bust the band up, there was a lot of this shouting was about songwriting. It was all of them arguing, and what the bloody hell do they know about it? They was saying, I wrote this song Paradise, and because it had my wife’s name in it, it was kind of autobiographical and I sung it, they fucking didn’t like that. They didn’t want. They got really snotty about that. They all went out and got drunk and came back and started telling me I couldn’t…said it’s an ego trip. Jeez, silly sods, they don’t even know what it means.

“And there was another song… Hugo Williams had in fact come down to the studio, he was helping me write, although we didn’t get anything out of it for that album, there was one or two that we’d written, we tried to record them and Lee didn’t want to do them. He wasn’t happy with them. I could see why. As I said earlier, Lee has a certain thing he can do. And Lee came to me one night, after they all got drunk, and said “I can’t do that, I can’t do that song. Can’t do that song.

“And I’m going, ‘You don’t wanna do it man, don’t do it’. And in fact, the American producer who was there, he came into the room and he was going “hey man, come into the studio, you and me and we’ll do this song. And when I was at Tamla Motown we did…” and all this. And I knew Lee didn’t have the balls to say no to the guy. And I said, I said, ‘Man, he don’t wanna do it. Forget it’. And the next night, I found myself in the position of them sneering at this Paradise song. And they’re saying, ‘You can’t fucking do that, you can’t fucking do that’. And I said, ‘Look man, you should give me the same consideration as I’ve given you. I’ve let Lee do what he does or doesn’t want to do’.”

“You see, it doesn’t even make sense what I’m saying. The whole thing was under pressure. we’d been touring America and all sorts of stuff. Relations between me and Lee were heavy. I don’t know what it was. Well, I know a little bit. [Laughs]. This argument happened and all of the band things that had happened….I felt isolated, and I had felt isolated because of that. Because I was writing the songs and they didn’t take any part in it. You know, all things like that. By the time the morning had come, we had all dug our heels in and the group had broken up. Shame. Yeah, shame.”

Did you realise at the time that with Dr Feelgood you were making something special? Joe Strummer and The Clash were fans, the Sex Pistols too….

“The whole punk thing, it was funny. I remember the first inkling I had, we’d done our year playing the London clubs and that. And we were off. And I remember one day, Dave Higgs from Eddie and the Hot Rods, he came round my house and he said “I had this gig the other night with this band called the Sex Pistols”. And I went: ‘What a great name for a band!’

“I remembered this name. And then, a short time after that I was in New York and I found a copy of the Daily Mirror. And it was on the front – the Bill Grundy show – ‘Oh blimey, it’s the Sex Pistols, what Higgsy was talking about!’ That’s all I knew about them. I didn’t know any of these people. But then gradually I did.

“Jean-Jacques Burnel from The Stranglers moved into my flat in West Hempstead. So I knew him. And then, there was one night I was down Dingwalls, and everyone was beating up on the Sex Pistols. A couple of them were in Dingwalls, and there was all of these Teds waiting outside, wanting to give them a kicking. And they came up to me. Anyway, I got a couple of people and we got out of there, got them into the taxi and away.

“And then the Feelgood’s bust-up happened, and I was in Oxford Street with my little boy and suddenly these geezers came running up. It was Joe Strummer, Mick Jones I think and it might have been Bernie Rhodes…I’m not sure. Anyway, but Joe came up to me and he’s going, ‘Man, man, you don’t know who I am’ and I’m going, ‘I know who you are, I’ve seen you in the paper,’ and he said, ‘What’s going to happen? What are you going to do?’ and I said ‘I don’t know, I don’t know.’

“Anyway, I got to know them. And then I realised how much influence we had on all of these bands, from The Stranglers onto The Clash, had been influenced by Dr Feelgood. And yeah. [laughs] I was completely falling to pieces then. My whole life was in ruins. I didn’t really know what was going on.

“But I did think, when we were so successful with Feelgood in the London pubs, I thought “wow this is going to lead to another big R&B craze, like the Stones caused in the 60’s.” Which didn’t quite happen like that.

“A lot of those punk bands, were young and they were like beginners. And they were very influenced by Feelgood. What they took from Feelgood was the simplicity and the energy. Technically a lot of them weren’t too clever, but they had the simplicity and the energy, plus they had the fashion thing. The look. It happened like that. But Dr Feelgood had a fair input into what happened there.”

What was the first song you wrote?

“The first song I remember writing for the band was She Does It Right. The whole thing was because I’d thought of that riff [starts singing the riff]. You know, that’s it. It took ages walking round and round the room, to think of the phrase for the title. I kept thinking of things like ‘She’s Out of Sight’ and I was thinking ‘No, you can’t use that. That’s fucking Stevie Wonder or something’.

“And suddenly it came into my head: ‘She does it right. Wow, got it!’ When you think: ‘She does it right, she does it right….hard every night just to make me feel alright.’ Right, ok. And the different verses are two lines. So there’s not a lot of words in there. But that’s not what it’s for. I think of that as the first proper one and thinking, ‘Yeah, I can imagine the band doing this!” and it came out as a song.”

I’ve heard you say before that after you’ve finished writing a song, you ask yourself if you can imagine Bo Diddley singing it. Do you still ask yourself that question?

“I haven’t asked myself that question for a long time. I did used to do that. It was about whether it was mean enough. I’m talking about writing songs for Lee to do. If you can imagine Bo Diddley doing it, you know it’s along the right lines.”

Lastly, have you got any advice to aspiring songwriters?

“It’s a secret and I’m not telling you!

“Actually, really, TS Eliot said that writing a poem or something like that “each one is a fresh raid on the inarticulate”. It means it don’t matter how many times or songs you’ve written, or how many things you’ve done, you don’t get a method really. Each one is that….you’ve just got to bash your brains out.

“I wish I had a procedure or technique. Like, write some songs now, sit down. But it’s much more chaotic than that. When I listen to miraculous songwriters like Chuck Berry or Bob Dylan or someone like that, I used to just think when I was writing songs, ‘Don’t listen to any Bob Dylan, man’ because it would put you off!”

Interview: Toby Sligo

Wilko Johnson plays at the Royal Albert Hall on 26 Sept. If you’re one of the lucky people who’ll be catching his performance, then tweet us what you see at @SongwritingMag.

Related Articles