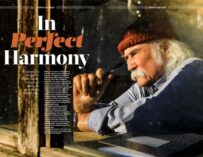

Joan Osborne: “I think everyone who makes music in modern America has been influenced by Dylan.” Photo: Jeff Fasano

Interpreting the work of Bob Dylan isn’t for the faint-hearted; thankfully this American singer-songwriter has the chops for the job

Joan Osborne is the multi-platinum and seven-Grammy nominated artist behind classic albums such as Relish and How Sweet It Is. As well as being a songwriter herself, Osborne has always enjoyed the challenge of tackling other people’s work. Her 1995 smash One Of Us was written for her by Eric Bazilian and through the years she has covered songs by Gladys Knight & The Pips (I’ve Got To Use My Imagination), Slim Harpo (Shake Your Hips) and many others.

Osborne’s ninth studio album, Songs Of Bob Dylan, takes this passion for interpreting songs one step further. Inspired by a series of Ella Fitzgerald albums, in which the legendary songstress sang music by the likes of Cole Porter and Irving Berlin, Osborne embarked upon the daunting challenge of taking on one of the most formidable catalogues in music history. These versions were first road-tested during a residency at New York’s Café Carlyle in March 2016 and a selection of them appear on her new record.

We recently caught up with Osborne to find out what it takes to interpret the music of arguably the greatest songwriter of all time…

How old were you when you first became aware of Dylan’s music?

“I think it’s almost impossible to answer that question. Was it hearing a nun sing Blowin’ In The Wind at a guitar mass as a kid? Was it hearing Rainy Day Women #12 & 35 on the radio? Dylan is such a part of our musical landscape, and has been since the early 1960s when I was born, that it’s impossible for me to say when I first encountered him. He’s just always been there.”

Has he been an ever-present influence throughout your career?

“Because of his massive influence on popular culture in general and music in particular, I think everyone who makes music in modern America has been influenced by Dylan. Just the notion that a person should sing their own songs instead of the songs written for them by a ‘professional’, which is something that Dylan’s success put to the forefront, was a given to people in my generation and the generation before us. That idea gave me a sense that being a singer could be more than just being an entertainer, it could mean being an artist.”

In what ways has your relationship with his music changed over time?

“To be honest I had some issues with what I saw as Dylan’s misogyny and cruelty when I dug into his work in my early 20s. Songs like Idiot Wind or Like a Rolling Stone seemed like they were written as personal revenge against women who had dumped him, which to me felt unnecessarily mean-spirited. Why use this incredible gift to take down an ex when you could use it to take down war profiteers or others who’ve legitimately earned the depth of your scorn? I would say that my attitude has mellowed over time, and I understand that I can appreciate Dylan’s complicated genius, and the songs that are full of light and love and tenderness and even righteous anger, without dwelling on the ones I have less affinity for.”

Did you always intend on releasing an album of Dylan material or did it grow out of the live residency?

“I was inspired by a series of albums that Ella Fitzgerald put out in the 1950s and 60s. It’s now called the Song Books and each album focuses on the work of a single writer or writing team, like Cole Porter or Duke Ellington or Rogers & Hart. I always thought it would be interesting to do my own updated version of the series, covering the writers that I love. So this Bob Dylan record is hopefully the first of many. The residency at the Café Carlyle was our opportunity to test the idea out, and see if we liked it and if the audience would respond to it. I’d love to continue the series, and I’m thinking about other writers that I might cover. I love Nick Cave, Tom Waits, Lou Reed. I think Lucinda Williams would be fun to try, though she certainly does a great job singing her own material. Someone suggested Neil Young, or Paul Simon. There are a lot of options!”

Joan: “Dylan’s writing … can stand up to many different readings in many different situations and still be completely powerful.”

How did you go about the unenviable process of choosing which tracks to include on the album?

“There were a few criteria. I did want to draw songs from throughout Dylan’s career, as he’s continued to write brilliant material into the 2000s. I also wanted to have some songs that everyone would know, like Tangled Up In Blue, mixed with less famous songs like Dark Eyes or Spanish Harlem Incident, allowing people to perhaps discover something new – in fact I didn’t know Dark Eyes until Patti Smith suggested it to me. Finding a way to reinterpret the songs was another criteria. If we were just going to record the tune like someone else has already done it then what’s the point?”

What was the next step, how did you take those songs and turn them into your own album?

“Much of what we did was trial and error. My co-producers Jack Petruzzelli and Keith Cotton and I got together in the weeks before the Carlyle shows and just tried out ideas by playing through a bunch of songs, experimenting with different tempos, rhythms, keys, time signatures, etc. Having a residency at the Carlyle gave us the opportunity to test out our new arrangements in front of an audience. We adjusted things as we went along, adding and subtracting. Keith and Jack are both very skilled musicians, so the process of playing the songs night after night also created a kind of instinctive interweaving of their parts, and I fed off of that with my vocal lines.”

Were you thinking, ‘I hope Bob likes this,’ at all during the process?

“I really don’t think Dylan sits around and listens to other people’s versions of his songs! We did have some contact with his publishing company, and they were very supportive of our efforts, which was nice. But we were more concerned with trying to do justice to the songs for ourselves and our audience, and didn’t really think about what Bob might or might not like. I’d be overjoyed if I got some kind of positive feedback from the man himself, but I don’t expect anything. Then again, he did recommend the album on his Facebook page…”

Were there any constraints that stopped you changing the songs at all?

“Yes, as much as we wanted to play with arrangements so people could hear something fresh in the songs, we also didn’t want to change them just for the sake of doing something different. The arrangements had to respect the song, enhance the meaning of the lyric or at least not diminish it. It couldn’t feel like a stunt. It had to feel like an organic reinterpretation of a classic.”

How much influence did your band have on the arrangements?

“I would say that their contributions were more than ‘influence’ because we were developing these arrangements together from the very first day of rehearsals. They were co-producers, not just hired hands playing predetermined parts.”

Did you have to change your singing style in any way to suit the material?

“Part of what I think of as my job when I interpret someone else’s songs is to find the sweet spot where my particular voice meets with the song in a way that allows both things to fully blossom. It’s not really about changing my style, but more like inhabiting a character the way an actor would. And I can sort of decide which roles to cast myself in when I choose material that I have an affinity for.”

Joan on Bob: “He’s sharply funny, heartbreakingly tender, sometimes vicious, sometimes generous.” Photo: Davis Arts Council

Was it a daunting challenge to tackle such a prestigious body of work?

“I’d had some experience singing Dylan’s songs in the past, and have even sung with him, so I didn’t have a lot of fear when starting the project. It wasn’t until about an hour before we went onstage for our opening night at the Carlyle, that I started to get anxious. What if people just hated the way we changed the songs? What if Dylan’s work had been covered to death and people weren’t interested in hearing yet more versions? I had one of those panicked moments where I didn’t know at all if the work we had done was any good or was just stupid. But the strength of Dylan’s writing means that it can stand up to many different readings in many different situations and still be completely powerful.”

Could you please pick a couple of tracks from the album and explain your relationship with them?

“I think what we did with Highway 61 Revisited is interesting. Dylan’s version is a big, stomping shuffle, which is sort of humorous. But I wanted to take a cue from the lyrics, which talk about the Bible story of Abraham and Isaac. I thought it would be interesting to use a musical style from the part of the world where the Bible stories took place, in this case a 6/8 Middle Eastern groove. On paper that looks like a random idea, but when we tried it with the song it gave our version an intensity and an energy that I think serves the lyric very well. Our tempo is faster than Dylan’s, and it makes these incredibly poetic lyrics come out in a rush, just a torrent of brilliance.

“Masters Of War is a song that I have always considered one of Dylan’s best. I remember first hearing it in my late teens and being stunned by the last line of the first verse, ‘I just want you to know I can see through your masks’. I guess people call that ‘speaking truth to power’ and I was just floored by it. I had debated whether or not to include the song on this record because it’s so intense, but the way things are going right now in America, we need intense songs to galvanize us, and we need our great artists and poets to help us express the things we’re feeling.”

Why do you think Dylan’s songs have such an enduring appeal?

“It’s hard to quantify. I guess I would say that Dylan found a way early on to use mythic, universal ingredients like Bible stories and blues-based language and combine them with beat poetry’s dive into the unconscious in order to write songs that feel both ancient and contemporary, both universal and intimate. He speaks about the human condition in an indirect and poetic way, so his songs resonate with different listeners in their different, particular lives. He’s sharply funny, heartbreakingly tender, sometimes vicious, sometimes generous. He ‘contains multitudes’ as Walt Whitman said.”

Last question, how did you feel about him winning the Nobel Prize in Literature?

“My favourite quote about it was from Leonard Cohen, who said, ‘It’s like pinning a medal on Mount Everest.’ I did get a kick out of his Nobel lecture, just hearing his terrific gravelly voice, and it sent me to the bookstore to buy a copy of Moby Dick.”

Interview: Duncan Haskell

Songs Of Bob Dylan is out now and for all the latest news, visit: joanosborne.com

Related Articles