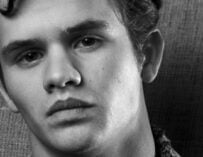

Erland Cooper: “I believe in critical distance and focus through limitations.” Photo: Neil Thomson

We catch up with a Scottish songwriter and soundscaper who is capturing the essence of the Orkney Islands through music

Scottish multi-instrumentalist Erland Cooper is another artist that seems to have had a very productive year. Back in May Cooper released the album Sule Skerry, the second in a triptych of records inspired by his childhood home, the Orkney Islands. Where the first album in the series, Solan Goose, paid homage to the islands’ birdlife, the second turned its focus to the North Sea. Made from various sound recordings, and featuring an ensemble class of collaborating musicians, it’s an intoxicating record which manages to capture our relationship with the sea – or at least, Cooper’s interpretation of that relationship.

More recently, Cooper released Seachange, an ambient companion piece to Sule Skerry. Created with producer, artist and guitarist Leo Abrahams it’s a continuous stream of work which is split over three movements, allowing Cooper to explore his source material in a different way. Here, Cooper walks us through his process and that ability to capture a sense of place in songwriting…

Has place always had a direct impact on your songwriting?

“Yes, in some form my working and living environment plays its part but I don’t believe you need to be in a certain landscape to write exclusively about that landscape. It can be real or imagined and escaping in your head is just as important as going there.

“This romantic view that you need to be surrounded by that place, a large studio with panoramic views in the highlands or Iceland or the desert to write about that place doesn’t work for me. While that could be idyllic, I believe in critical distance and focus through limitations. I have to visit a place, take notes, sketches, field recordings and ideas back with me from a deep immersion or experience but it’s the separation from the source that really helps me strip out to the cutting room floor. It just helps me try and capture the simplest or most evocative part that informs me. This is something I’m learning from landscape artists like Norman Ackroyd or the film director Sally Potter. I’m not trying to be too overt with the work I do, subtle narrative intrigues me, which I hope, leaves room for interpretation or maybe just internal reflection.”

Did you undertake much research before starting the writing of Sule Skerry, or were you already familiar with the topics you wanted to write about?

“I was lucky, I grew up in a large family on the Orkney Islands, so I would say the first few decades of my life informed the writing process in some way. I think that touches all the work I do. The sea, skies, cliffs, community, birds and wildlife dominate in every way on the islands and the further I go away from the place, the more I want to return. It’s like my Magnetic North.

“With each of the records, I brought someone with me to Orkney as an outsider. It’s really interesting watching how someone that isn’t from a place, react to that place, the landscape and its stories. It’s there where I find a deeper inspiration. It teaches me to see a different way and to listen and reflect more naturally. The poet George Mackay Brown and perhaps the less celebrated Orcadian filmmaker Margaret Tait used to find the magic in the every day and so in studying, or simply enjoying their work, it informs me and gives me direction. Much like a nautical map, it acts like a guide and helps me navigate through a creative and decision-making process.

“With that in mind, I didn’t intend to release Solan Goose. I was simply using it as tool to ease a busy mind in a city and try to calm me and evoke some form of childhood memory. It distracted my brain while travelling and transported me to a place. When it was released, I had to create a new tool and ultimately a new record. As such, I am working on the third and final one – all very much for the same reasons to be honest. However, I think they will all come together and makes the fullest sense that way.”

What were the major differences when it came to writing about the sea rather than the air?

“All the elements play a part in these records but mostly how they interact or depend on each other but the sea in Orkney rules, with its size, scale, scope, colours, smell and sense of space. It wraps around Orkney like a glove but holds and smashes it daily. I think the major difference is in the rhythm of the sea, its ebb and flow changes several times a day and depending on the weather, really dictates the terms. While hanging off the back of the NorthLink ferry into Stromness, you can see the engines churn against the tide. It creates these cross-rhythms and almost counter-melodies. I hope that is reflected in the music in some way.

“There is also a great uncertainly with the sea. It can change at any time and can give the impression of comfort and safety but has the ability and power to damage, effortlessly. I wanted this record to reflect safe havens, safe harbours of our own and protecting them from the elements.”

Erland Cooper: “I love amplifying quieter sounds and playing with fragility.” Photo: Alex Kozobolis

Do you think you can hear those differences in the resulting albums?

“I’ve tried not to compare too critically but I hope the dynamics in this record are a little larger in scale as the narrative dictates that to me. I think this is to do with the power of the sea, genuine calm after the storm, playing with distortion and subsonic frequencies but also playing with quieter moments by contrast and sequence. I love amplifying quieter sounds and playing with fragility or perhaps my insecurity as a tool to create something more secure or empowering, playing to natural and unnatural dynamics, space and simplicity.”

Can you give us some examples of specific places on the Orkney Islands that have seeped into your writing?

“I recorded inside some of my favourite acoustic spaces on the island, as well as captured impulse responses of these spaces. This meant I could then use these captured reverbs in the mix process back in my studio and I could put anything else, for example my string ensemble, inside the space without taking them all to Orkney. These included my local town hall in Stromness and a Neolithic cairn called Curween. I also played back and re-recorded electronic drones inside a World War II naval gun embankment.

“The space looked out to sea and my drone echoed across the harbour, across the short passage to the islands of Hoy – a familiar viewpoint as a child. I re-recorded that back in and it is the sound you hear underneath the song Creels. To me, it then feels like the landscape and sea, in particular, is genuinely a part of the record in itself as much as the violin or soprano. All of this could just be for my own satisfaction but that’s ok, it’s just part of a creative process and gives me the joy and perspective to know what to discard and retain, and name.”

When you’re making field recordings are you thinking of them in terms of how they might end up in your music, or are you making them for their own sake?

“Good question, I would say, both. I think I recorded an 86-year-old semi-retired fisherman for two hours to get less than 10 seconds of audio used on the record. I always remind myself that a photographer can take a hundred pictures but is only after one shot that actually means anything or captures the narrative. I take comfort in that and am interested in the creative process. So much is made, saved and discarded in the edit. I’ve also noticed, with field recordings, what you expect is going to work really well at the time, generally is ok but it’s the stuff you dismiss that has a magic to it.”

Did you have to prep your musicians about the Orkney Islands and the story within the music?

“Generally no, I would work with them in the studio back in London. As the session continued, they would naturally become increasingly immersed in the narrative and that was a joy to watch and explore. For me now, collaborating with talented people is the lifeblood of the process for me. Writing for and recording a true classical musician is like watching a bird of prey hunt, it’s majestic. The collaboration then comes to life further in the live shows and then when I get back to the studio, I can write for the individuals I know and care about. I hope by the last record of the trilogy, it will all come full circle.”

Why do you think nostalgia for childhood provokes such strong creativity?

“For me, it’s not a romantic or tinted nostalgia I’m working with. Like many, my teens were challenging but there was purity of thinking and with innocence comes a single-minded thought. There was, of course, the naivety and brevity of exploration but my childhood reminds me of a particular place, a place that is the polar opposite of where I spend my time at present.”

Do you feel any responsibility to keep these local stories and myths alive?

“I feel a sense of joy in doing so. They are kept alive quite naturally on the islands. It’s not a lost language or dialect but it is a rich one to celebrate. I adore hearing presenters on BBC radio, for example, pronounce the local words. Storytelling is what humans do so well and in Orkney, it’s the lifeblood I think.

“However, I do now have a sense of responsibility in other areas. Over the last two years, I have an increasing number of personal stories shared with me directly about how some of my music has helped overcome personal anxiety or grief. I find it very touching and moving and deeply humbling. I can only work harder and clearer and if it helps me, hope that others find those very same things that I do. I think subtly and sub-narrative is as important as being overt.”

Have there been times when you weren’t successful in bringing a specific place/story to life through song?

“Well, I have an orphanage of sounds and song. Everything I write that doesn’t get used bounces off the floor and gets dropped in there. It eventually finds a home… in some form or another.”

Are there any albums by other artists which you feel capture the essence of a specific place/or inspired your own ability to do that?

“All I’m ever trying to do is write Peter Maxwell Davies’ Farewell to Stromness… I think Andrew Wasylyk’s The Paralian has a wonderful ebb and flow and it’s not just someone else with an affinity to the North Sea, it feels like the landscape itself has helped write the record. I think the work of landscape artists like Ackroyd, filmmakers like Tait, authors like Robert Macfarlane and Amy Liptrot, architects like Wolfgang Buttress inspire me greatly, more so than probably musical artists. They truly know how to capture the honest essence of place, feeling or time and make it look effortless. That’s the key I think, working exceptionally hard to simply make it look easy. That’s all I ever strive to do and in the end, it doesn’t really matter how something is put together, there are no rules but ones you give to yourself.”

Lastly, is there anything you would like someone listening to Sule Skerry to know about you and your music that you don’t think they already know?

“I’m not sure how to answer that. I’ve tried for the first time in my music to separate my ego further out of the work itself or to at least push it a little further to one side. That’s remarkably difficult to do; they always creep back in and fill us with conflict. I’ve just tried to forget about caring about what people think, respect what I think and to go deeper, much deeper into caring about how it makes me feel.”

Interview: Duncan Haskell

Sule Skerry and Seachange are both out now, and Erland will be performing the Orkney triptych at London’s Barbican Hall on 13 June 2020. For more info, head over to erlandcooper.com

Related Articles