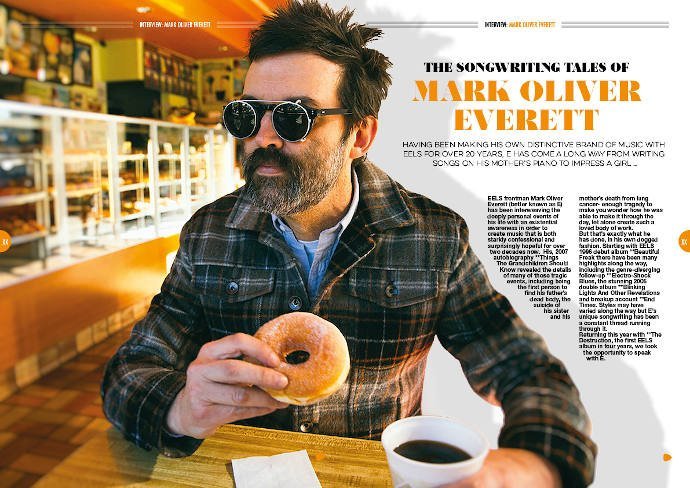

After making his own distinctive brand of music with Eels for over 20 years, E has come a long way

Eels frontman Mark Oliver Everett (better known as E) has been interweaving the deeply personal events of his life with an existential awareness in order to create music that is both starkly confessional and surprisingly hopeful for over two decades now. His, 2007 autobiography Things The Grandchildren Should Know revealed the details of many of those tragic events, including being the first person to find his father’s dead body, the suicide of his sister and his mother’s death from lung cancer- enough tragedy to make you wonder how he was able to make it through the day, let alone create such a loved body of work.

But that’s exactly what he has done, in his own dogged fashion. Starting with Eels 1996 debut album Beautiful Freak there have been many highlights along the way, including the genre-diverging follow-up Electro-Shock Blues, the stunning 2005 double album Blinking Lights And Other Revelations and breakup account End Times. Styles may have varied along the way but E’s unique songwriting has been a constant thread running through it.

Returning this year with The Destruction, the first Eels album in four years, we took the opportunity to speak with E.

Do you remember the first song you ever wrote?

“The first one that I remember was when I was very young, probably like 10 and I had my first girlfriend. My mum had an upright piano in the back of the house and I was making up a song about this girl.

“At that point, I was always fantasising that I would play it to her someday but I don’t think I ever had the nerve to. You know for years I never entertained the idea that this could be something I would do for my job, or how I’ll make a living. It never occurred to me that it was a possibility.”

When did that change?

“That changed in my late teens. All my friends had gone off to college and I didn’t have any plans. For some reason I didn’t think I was going to live to the age of 18, then I was 18 and it was like, ‘Oh I’m still here and everyone is going to college. I don’t want to go to college, what am I going to do?’ My girlfriend said, ‘Well the only thing you really care about and are passionate about is music. You’re good at it too, so why don’t you pursue that?’ and that was the first time I went, ‘Well maybe she’s right, since I don’t know what else to do?!’”

Did that alter your approach to writing?

“Then I really tried to get serious about it.”

You then had success with Beautiful Freak, how easy was it to follow that up?

“I think it would have been harder if I had done what I was being advised to do after the first Eels album, which was basically to do part two of that album. Then it’s hard if you’ve put everything you had for so many years into one album and then you’re supposed to replicate it or something. Luckily I didn’t take that advice and I made something completely different with the Electro-Shock Blues album, much to the chagrin of those that were advising me at the time – but I’m glad that’s how it went.”

It’s now 20 years later and you’re still doing it…

“I look back at that moment as one of the main reasons that I’m still here 20 years later. At the time it was a really difficult thing to do. I ended up firing my manager over it and he was like a father figure to me. It didn’t do well commercially, it completely bombed. The record company and everyone else were having a really hard time with it. So it was a brave thing to do at the time for me, but I think it was also smart in that I just followed my heart and did what I felt like I had to do as an artist.”

To this day are you consciously aware of making sure an album is not too similar to the previous one, or is it more effortless than that?

“It’s pretty effortless in that I get really fed up with one thing when I’ve finished the album, and the sound of one tour and all that, you get done with that after a year or two and you just naturally want to go somewhere else.“

That cycle of recording, releasing and touring must be one of the hardest things about the job?

“Well, I was always quite happy to roll with it. I would often get home from a tour and start the next album the next day but then it got to a point where if you do any one thing too much in your life it will catch up with you. It finally caught up with me after the last album, The Cautionary Tales of Mark Oliver Everett. After that I just really had to take a break, that’s why I didn’t put anything out for four years. It was just too many years of really intense focus and work and nothing else. So I had to give it a break.”

Were you still writing for yourself while having that break?

“Normal people would go on normal vacations here and there over the years and I just never did, it was all very imbalanced. Just work, work, work and then break, break, break. Whatever I do, I really do it! So I really set out to not work at all and, for a while, I thought I was done, I may never work again. That’s how worn out I was. Then, it’s a nice way to work if you have the luxury of time, where I would only write and record something when I was really inspired. Like if I woke up one morning and was like, ‘Oh I’ve got to write this song,’ then I would do it. Then it might be six months before the next one. I didn’t set out to make an album. I didn’t know I was making an album for most of it.”

Was there a set way that the songs tended to start?

“No, that’s one of the fun things about it. There’s no recipe and there’s no structure to how a song was written. It’s always different.”

At what point did you accept that you had enough songs and were ready to make an album out of them?

“I almost always write them and record them at the same time. It’s rare that I write a song and don’t record it soon. So somewhere during the break I started to notice that there was a pile of songs mounting up and I started to look at them and listen to them and see how they sat together and see what themes were emerging. Then I started to get an idea for an album and I got rid of some songs and had a better idea of what would help it, to add to it.”

How similar were those demos to what we’re now hearing?

“I don’t do demos, sometimes I do a shitty little cassette to make sure I remember how the chords go but for the most part I write it and record the record that day or the next day.”

What was the role of Mickey Petralia?

“He’s the co-producer of 3 songs.”

Did he and the other Eels band members contribute to the writing?

“Yeah, I would say maybe at least half the album was co-written with Koool G Murder and there’s one that was co-written between me and our guitarist P-Boo.”

Is that a process you enjoy?

“Yeah, I mean the reason for collaborating is to get something out of someone that you’re not going to get out of yourself. That’s always fun and exciting.”

Do they also help with the lyrics?

“No. These guys are musicians, they don’t have anything to say. I don’t ask them about lyrics.”

Have you learnt to strip your lyrics back as part of the editing process or do they come out in the way we hear them?

“When I started writing songs back when I was that teenager with the girlfriend who said, ‘Hey why don’t you try to make something of yourself with music,’ I was writing songs that were way too long and had way too many lyrics. As time went on I realised that the kind of songwriting that I really admired the most was really succinct and that there was a real art to telling a story in a very small amount of lines. I just worked over the years at pruning my writing so it would get to the point. The other thing that was going on, at the same time, was I kept working more and more at really trying to get to the point of what’s at the heart of the matter, whatever the matter is that I’m discussing. Whatever I’m talking about in the song I will try to get to what’s underneath that and what’s the truth at the bottom after you’ve peeled off as many layers of the onion as you can. When you combine those two things then that’s what we have – succinct truth, whenever possible.”

Who were the other writers who inspired you to get to that point?

“So many. But one that was a huge influence on me as a little kid was John Lennon and his Plastic Ono Band album which oddly was my favourite record when I was 10 years old. There are barely any lyrics to some of those songs. Things like Mother and Isolation, it’s like you look at the lyric sheet and there’s barely anything there, but it says so much. That’s fucking genius, undisputed.”

As well as inspiring the method and succinctness, did listening to someone like John Lennon baring their soul make it easier for you to do the same?

“I mean luckily for some reason that record just seemed like a normal thing for a 10-year-old to listen to when I was listening to it. It just seeped into my unconscious probably and I just thought, ‘That’s how you should do it.’”

Do you make notes of feelings and events when you’re experiencing them or is it all done in the moment of writing?

“More often than not it’s all done in one moment, usually in like thirty minutes, but then there’s some that are different. Some that takes days, weeks and even months, but for the most part, the majority of them are quick.”

Eels’ Mark Oliver Everett in Songwriting Magazine: “It’s not like I have a shortage of songs about shit storms”

Are you good at knowing when a song is finished?

“I try to stick with the, ‘If it’s not broken don’t fix it” rule as much as possible. I’m always mystified by the way those people work where they do their tracking of the record and then they do all the mixing after that. I’m always mixing as we’re tracking. As we put each instrument on and the vocal, each time we add something to it I mix it to the best mix I can get it to at each step, so then it’s easy to know if it’s good and it’s working – ‘I’m excited by it let’s not fuck it up now, let’s move it on to the next one.’”

Have you always done it that way?

“I mean it’s tough. Mickey, for example, he kind of is that type of guy who likes to work really slowly and I guess to guys like him in their minds it’s more of an organic process, where, you let stuff evolve. Either approach is great if you get good results out of it. My thing is I start to go crazy if I spend too much time on one thing. I get bored and it gets tedious and I just want to get onto the next thing. But the combination can be good. What happened in this case with the three songs I did with Mickey was we started off at his studio with that slow organic process where it was like, ‘We’ll see what happens,’ and then, at some point, I would take them back to the studio and I would finish them up quickly. That was a good combination and I thought that worked pretty good. But my process is also a lot like that, it’s just a faster version of it. What I love about making records is all the happy accidents and to do that organically is what’s exciting about it, I just tend to do that faster than some of these guys.”

In that case, what do you think makes an ideal co-producer?

“Well, whatever gets you good results in the end you know. It doesn’t really matter how they go about it as long as everybody likes how it ends up.”

You mentioned earlier that a thread revealed itself on The Deconstruction…

“One of them is that I felt like there’s a lot of compassion in some of the songs and just trying to be helpful and understanding to your fellow man in general. And the idea to remember that we’re all trying to do our best with what you’ve been given.”

Do you ever see that as your role as a songwriter – to help people through tough times?

“I mean I don’t consciously think of that when I’m writing a song but it is something that seems to happen. For example, when I wrote my book I had a lot of people come up to me on the street and talk to me about the book specifically because they feel like it gave them hope. They feel like, ‘If this guy can get through all that shit I can deal with my shit.’ I’m just so happy to be able to be that person for people, it’s such a great thing but it’s not why I set out to do it. All these songs where it sounds like I’m talking to somebody, in a lot of cases I am specifically talking to someone in my life but they’re also always simultaneously a message to myself. I’m not an expert on any of these topics I’m not saying, ‘Here’s how you do it.’ They’re notes to myself also.”

But when they do strike a chord with someone it must be the cherry on the cake?

“Yeah, that’s exactly what it is, the cherry on the cake. You didn’t expect that and it’s like, ‘Boy am I surprised.’”

Perhaps if you’d set out to do that it wouldn’t be so sincere…

“That’s exactly right. You know there are little ways that I do become conscious of it, or maybe it’s subconscious. Like in the case of the song Today Is The Day on the new album. I don’t get specific about what change I am talking about making in my life in the song, I just made it about the phenomenon of realising you need to change something in your life. Imagine if I’d said, ‘Don’t be worried, today is the day you’re going to stop eating cheese!’ Then it becomes a very specific song and at that point, it doesn’t help anybody but me. So I think there is a subconscious thing where I’m aware of that phenomenon. I don’t want to get too specific if it’s going to ruin it for the world. So this way anybody could hear that song who is aware that there’s something in their life that needs to change but they haven’t gotten around to it yet and they might hear this song at the right time and it might actually help push them forward a little bit.”

Some songwriters that we speak to are a little masochistic in the way that when they experience something traumatic or unhappy they’re thinking that it could be turned into a song. Does that ever cross your mind?

“I call those guys amateurs because, for those of us that have just been through a shitstorm of shit in our lives, I can’t imagine ever being glad about some shit in my life because it’s going to make a good song. I am genuinely always trying to avoid shit storms. I’ve had enough. It’s not like I have a shortage of songs about shit storms, it’s not like, ‘Oh good, here’s another shit storm for a song.’

“I think people often have the lazy observation of looking at the Eels albums and thinking it’s bummer rock or whatever, but that’s really not paying attention to it. It’s completely the opposite. It’s always been about getting to a positive place and it’s the shit storms that make the positivity meaningful and believable.”

The Deconstruction struck us a very hopeful album…

“I think so too. But I think that’s probably true of all of them, more or less.”

When the record is done and dusted, are you already onto the next thing?

“The fun part is making it and then after that, it’s just sort of like a job and it’s no fun. Putting a record out is the worst part of it. You just have to let go of it as much as possible once it comes out, and then you just look forward. The performing part is fun too.”

Is it a challenge to put new songs up against those old favourites which you know will always go down well?

“It’s pretty easy for me. It’s very natural to just look at lists of songs, look at the album covers and see which ones jump out at you, which ones you feel like playing. It does get harder and harder the longer you do it because there are so many songs that just aren’t going to fit into 90 minutes. You’re always going to disappoint someone by not playing their song but what can you do.”

But it must feel amazing that a song you wrote back in 1996 still has an effect on people?

“Yeah that’s crazy, I can’t even fathom that. I can’t fathom that I got to make one album let along all of these albums. It’s still miraculous to me how lucky I am.”

Do you feel like the break has reinvigorated you?

“I really don’t know what happens after this. I might not know until I get back from this tour and see what I feel like, if I’m going to relax a little or get right back into it. I don’t know.”

With that in mind, do you have any ambitions left as a songwriter?

“I always wish I could figure out a way to smash it all and write a new code. I’d love to be one of those innovators who just completely comes up with a whole new genre. Is that ambitious enough! I’ve spent a lot of time in my life really thinking about that and trying to figure out what is it that has not made itself clear to me so far. I’m okay with my little corner of the world and what I’m doing. I do feel like it’s my thing enough, I do feel like I have something to contribute to the world in whatever small way and probably the guy that’s gonna innovate a whole new genre is probably going to be a younger guy than me, but you never know. I could still surprise everybody!”

If you told that 10-year-old boy sitting at his piano writing a song about the girl he had a crush on that he’d still be doing it all these years later what do you think he would have said?

“I think about stuff like that all the time and that’s what I mean, it’s miraculous. The 10-year-old me would have said, ‘Get the fuck out of here, that’s not going to happen.’”

Interview: Duncan Haskell

Related Articles