Our guitar and production aficionado Dave Chrzanowski shows how different scales can be used to write riffs, melodies and solos

It’s true how the old punk saying goes; you do only need three chords to write a song. However, it’s what you do next which defines the song. A well-written riff fleshes out a song and can make it truly memorable. Here, we’ll be talking mainly in guitar terms, but the theory works for any stringed instruments and piano.

What’s A Riff, Melody or Solo?

Firstly, let’s get to grips with what we mean by riff, melody and solo. A riff is simply a short “phrase”, or collection of notes, either repeated throughout the song or played only once, often heard during the song’s intro. Queen’s Killer Queen features a prominent riff, and is a prime example of what we’re talking about. There’s no hard or fast rule, riffs don’t have to be complicated, take Sex Pistol’s Pretty Vacant; you’ll see the intro riff only has two notes, A and E:

Sex Pistols’ Pretty Vacant riff tab

Solos are relatively self-explanatory. In a contemporary verse-chorus structure, the solo will usually fall between the second chorus and third verse. Although this is not always the case. Chuck Berry’s Johnny B Goode breaks away from this rule, by placing a solo during the intro.

Melodies differ from riffs and solos. Although riffs do contain melodic motifs, they tend to be much more rhythmic than melodies. A melody is tuneful, it sticks in the listeners head and is often the reason we fall in love with songs in the first place. Quite often the piano or guitar melody will follow the vocal melody, or vice versa; if it’s catchy, it’s down to the melody.

Scales And Keys

For those of you who were forced to sit and learn scales for hour after boring hour, you don’t know how lucky you are. Knowing your scales will make writing riffs, melodies and solos much easier. Knowing which scale to use and when is a great talent to possess. For example, the pentatonic scale is popular in many genres, and works with all styles. Whereas songs like R.E.M.’s Losing My Religion makes use of the Aeolian mode/scale. The key is to find the scale that fits the song in question the best.

C blues scale

C minor pentatonic scale

However, if you haven’t practised those pesky scales, don’t worry. The easiest scale to learn is perhaps the pentatonic, so-called as it only contains five notes per octave. A variation of the pentatonic is the blues scale. The blues scale contains six notes; five notes from the major or minor pentatonic plus one chromatic note – a note that doesn’t belong to the pentatonic scale. Generally, blues scales sound good in modern music, as blues is the foundation that contemporary music is built on. Alternatively, try using your ears, jam some ideas and listen to what sounds good.

Having chosen a scale that suits the chord progression, key and style of the song you’re playing, the notes of that scale can be played in any order to form a riff, melody or solo. But the best place to start your lead parts is with the root notes of the chords, as the root notes will help you find the structure of the song.

Remember, keep practising and memorise two or three scales, and learn them in different keys so finger positions up and down the fret/keyboard become apparent; having these in your arsenal will be beneficial when writing lead parts quickly when necessary.

Moods And Formulas

Often people will describe songs written in major keys as “happy” and songs in minor key as “sad”. This is an over-generalisation and isn’t always true. Take the minor blues scale for example. It is frequently used to solo over major chord progressions, and is recognised as the most versatile scale.

The formula for adapting a major scale to a minor blues scale:

1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7 represent the notes in the scale.

In an A major scale, those numbers become A, B, C#, D, E, F#, G#.

Turn that major scale into a blues scale by flattening notes 3, 5 and 7.

So, the formula for a blues scale is 1-b3-4-b5-5-b7 which in A minor translates to A, C, D, E♭, E, G.

The lead guitarist can play an A minor blues scale over any chord progression in the key of A, featuring major, minor or diminished chords, to create a riff or solo.

Techniques

Consider using hammers and pulls, bends and muted notes to make riffs and solos more interesting. Even the simplest lead part can sound more complex by throwing in a few tricks. Also, avoid jumping around the keyboard or fretboard, by selecting notes that are next to or near each other gives solos a rhythmic flow, making them easier to play.

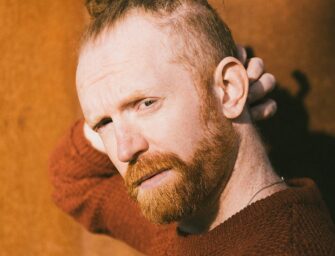

Words: Dave Chrzanowski

Read more tips features like this, along with artist interviews, news, reviews and gear in Songwriting Magazine Winter 2019

Read more songwriting tips here > >

Related Articles