Jamie Floyd: “I was known as the Grammy-nominated waitress, with a lot happening in my career, but without a publishing deal.”

The Nashville-based songwriter shares her twice Grammy-nominated journey; from industry challenges and advocacy to insights on authentically telling your story

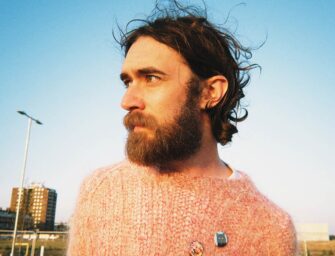

Jamie Floyd is a twice Grammy-nominated singer-songwriter based in Nashville. Floyd has established a noteworthy solo career as an artist, recently releasing the single Sad Girls Do. As a writer, her songs have been sung by artists such as Kelly Clarkson, Miranda Lambert, Kesha, and Madi Diaz to name just a few. However, her journey to where she is today hasn’t always been a straightforward path.

Floyd gained industry attention in 2015 when she received a Grammy nomination for writing the title track of Ashley Monroe‘s album The Blade. Despite this recognition, she still had to supplement her income by waiting tables in Nashville. Her story as the ‘Grammy-nominated waitress’ became a key storyline in the critically acclaimed documentary The Last Songwriter, showcasing the challenges faced by songwriters in the age of digital streaming. The documentary was also used to advocate for the Music Modernization Act, aiming to protect the future of songwriters.

Though The Last Songwriter was filmed almost a decade ago, it remains just as relevant today. Even with changes made, today’s top and emerging songwriters continue to have to advocate for fairer pay, making Floyd’s decision to speak up more relevant than ever. Floyd shared her reasons for participating in the documentary, the story behind her song about chasing dreams in Nashville, and her best piece of advice for aspiring songwriters…

Read more ‘5 Minutes With’ interviews here

So, can you tell me about how you were approached to be a part of that documentary?

“I had been a fan of Marcus Hummon, who has written lots of hits for the Dixie Chicks and Bless The Broken Road, among other incredible songs I’ve always loved and respected. I was approached a little before the documentary was being filmed by NSAI [Nashville Songwriters Association International], which is our lobbying group for songwriters. They go to Washington to advocate on our behalf. Bart Herbison, who heads up NSAI, noticed my story.

“At the time, I was known as the Grammy-nominated waitress, with a lot happening in my career, but without a publishing deal. I was making waves, bucking the system, and getting through gates without permission, which caught people’s attention. Bart asked if I would be willing to go to Washington and speak up because I am a bit of a rebel. It’s a sensitive situation because, as an artist and songwriter, you want a relationship with DSPs and labels, but our interests differ legally and regarding copyrights.”

Jamie Floyd: “There’s a tendency to quickly forget and push aside the artistry that comes with time.”

How did you know it was worth the risk to participate?

“When I aligned with NSAI, Bart asked if I was willing to speak up based on my career and my songs, understanding the potential ramifications but also the potential for positive change. If I was willing to do it, I would be joining a team of people who believe in doing what’s right. It was risky for my career, but I knew it was the right thing to do. So, I started going to Washington, lobbying, meeting with congressmen and senators, playing my songs, and telling my story.

“As I became more outspoken, Marcus Hummon approached me about making a documentary in partnership with NSAI to educate the public and lawmakers about the bill they were working on. He wanted to show them, rather than just tell them, what we were trying to do. They were looking for a songwriter who wasn’t a household name like Garth Brooks, but someone who could represent what the current climate was doing to our generation and what it could mean for our culture if that generation was extinguished. He warned me that I’d have to highlight some uncomfortable truths, but I knew it was important. That’s how I got involved, and eventually, they chose me to be the through-line of the documentary.”

Did you write the song What I See In Me before or after the Grammy nomination?

“I wrote What I See In Me when I was 22, so it was before the nomination. I wrote it with Rachel Thibodeau, an incredible songwriter here in town. We wrote that when I had first dropped out of Belmont and was waiting tables, going through a phase of wondering if I had made the right decision. That song dives into that feeling.”

If you could make a documentary today about an issue in Nashville’s songwriting scene, what would you highlight?

“There is a culture in Nashville that imposes an expiration date on artists and songwriters. This isn’t limited to young women; it affects everyone. There’s a tendency to quickly forget and push aside the artistry that comes with time. I’m not saying that there aren’t young prodigies and incredibly talented people who deserve recognition. I work with many young artists who are hardworking and deserving. But I think there’s a need and benefit creatively to have more balance between the focus on the newer artists and the more experienced artists and songwriters.”

Jamie Floyd: “Never write someone else’s song. Whatever it is, make sure it’s all yours.”

How would you showcase it as part of the music business?

“I’d shed light on how the trend for so long with the gatekeepers in the biz has been to focus on recreating what has already worked without regard to what’s newer or more established creatively, which feels based in scarcity. I think we’re losing out as an audience so much because of this fear-based approach. And I’d also highlight further that experience often leads to richer, deeper art, especially in songwriting.

“For example, the songs I wrote at 11 could never compare to what I’m writing at 38. It’s not about the songs being better or worse, but about the depth that comes with experience as a storyteller. I crave this depth as a consumer. When I hear songs from artists like Brandy Clark or Brandi Carlile – who seemingly started their artist careers a little later – there is a unique value in their work. I think so many artists are often not given the spotlight they deserve. Even artists like Kacey Musgraves, who has been wildly successful for a while now, face this issue. Despite her incredible artistry and the success of her songs, you can’t hear those songs on the radio, which is mind-blowing to me.

“This doesn’t mean there’s no space for the newer crowd. We need the new generation, and their contributions are important, as is the art from the more established artists. After being in Nashville 20 years now, I’ve seen so many brilliant artists be cast aside simply because they’ve been around too long.”

What’s the best piece of songwriting advice you could give?

“Never write someone else’s song. Whatever it is, make sure it’s all yours. Earlier on, I wish I had more of an intention to tune out the noise, the rules, the genre markers, the industry voices, and all the things that can really make you forget who you are as a writer. It’s not bad to consider those things, but do your best to get rid of all that noise. Write to hit the nerve of what you actually feel, no matter how terrifying that is.

“If you’re brave enough to say it, what naturally comes out of you is what will set you apart. Of course there can be an editing process, but so many times I edited myself right out of my own songs, thinking I had to hit all these rules that weren’t even mine. I didn’t discover this until pretty late… might be great, it might be terrible, but at least it’s mine. I always aim to feel, ‘This love/joy/tragedy is mine. This sounds like me.’

“You take a big risk in doing that, but once I started coming into the room as a songwriter, saying, ‘This is me. This is what I do,’ and offering that instead of trying desperately to keep up with trends or whatever the ‘it’ thing was at the moment, I was so much happier with my output and I’ve had my most success with songs I’ve approached that way. It always surprised me! But when I was pressured to not be the writer I actually am every day, things got really hard, cloudy, and painful. I’ve learned that the more I’ve leaned into this practice, the more fulfilled and inspired I’ve been.”

Related Articles