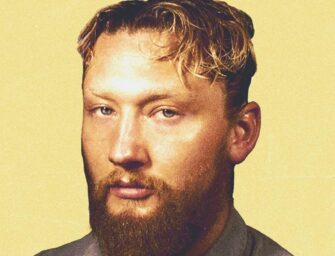

Yellow Days: “Especially nowadays, you’ve got to say what’s going on.”

Lost years over, George van den Broek returns with an album that finds him fully focused and ready to sing

Performing under his artist’s name, Yellow Days, the distinctively sonorous voice of George van den Broek first emerged while still in his teens. Gaining attention with the lo-fi intimacy of his debut EP Harmless Melodies, he’s become known for using that compelling vocal delivery to bring to life music that fuses an army of sounds and styles. His is a singular artistic vision, unconstrained by commercial expectation, that’s perhaps best summed up by 2024’s Hotel Heaven – a concept album that intertwined psychedelic indie-pop, funk, and soul with a vividly imagined narrative world

His latest release, Rock And A Hard Place, marks a significant evolution: a record conceived after a period he has described as his “lost years.” Influenced by soul legends like Stevie Wonder and Marvin Gaye, the album balances rich, vintage-inspired arrangements with raw emotional honesty, signalling a mature, fully realised creative resurgence. As witnessed on spectacular singles Special Kind Of Woman, I Cannot Believe In Tomorrow, and Sharon, it’s the result of a prolific songwriter and recording artist honing in on a sound he truly believes in…

Read more interviews with renowned songwriters

The press material for the new album talks about you having the “lost years.” How did that period of dislocation shape the songwriting going forward?

“I was still releasing music as Yellow Days, but I was really focusing on writing music for other people. It was a way of burying my head in the sand. Songwriting is the bedrock of what I do. Singing is my main weapon, but then songwriting is the backbone. So, ‘the lost years,’ I felt I wasn’t really wanting to write as me, as my artist project.

“It was, like you said, a dislocation. As a writer, having to adopt the Yellow Days identity became more difficult. It was much more fun, or a good distraction, to wear someone else’s persona. So, in terms of writing, it was a way of putting on somebody else’s mask and thinking from their perspective. I worked with a bunch of up-and-coming artists; a lot of them were friends here in London.

“People around me, my friends and my wife, would be like, ‘Why are you not writing music for your stuff? Why are you always doing these projects?’ It was a way to distract myself because, essentially, I found it hard to tap back into what the identity of Yellow Days was. I’d explored so many different sounds that I ended up in a mind soup. Then, alongside other things that were happening in my life, it was really hard to jump back in. But, I got there in the end with the new record, Rock And A Hard Place.”

Was there a particular moment that helped you rise, phoenix-like, from the flames?

“There’s a tune on the album called California, which was a big breakthrough, because that was going to set the tone for the sound of the record. Through the melody and the accompaniment, it could open up this space for the voice to get really big again.

“That was another thing, not wanting to do big singing for a while. I fell out of love with that – and, as a writer, wanting to pull at every lever and explore things, like a monkey in a spaceship pressing every button. I’ve been in music, had albums out, and had an audience since I was a kid, so these growing pains have all been done in public. I’ve definitely lost the patience of a lot of people along the way by being a little too explorative, or not waiting long enough to decide, ‘Is this concept album worth people’s time or should I keep it in the back pocket?’

“When you write from someone else’s perspective, you take yourself out of the equation. I could still have fun with music, but be somebody else while doing it.”

But you were still releasing music semi-regularly – it wasn’t like you’d disappeared completely.

“Exactly. My problem has always been, and people who work with me find it infuriating, that there’s too much music going on. I don’t really know what I’m doing. I’m still releasing a tonne of music, because I write maybe an album’s worth of music every three months. It’s a prolific writing habit, and some of it’s better than others, but it’s all cogent music of different genres.

“It spews out of me in a way that makes the people who try to manage me really unhappy. They fall in love with something, and then I move on to the next thing, and they go, ‘Well, what about this?’ We get into these horrible, tangled-up conversations about what I’m doing.”

Yellow Days: “People want to hear someone being honest.”

Would the songs on Rock And A Hard Place have been written in one of those three-month blocks? Or are you cherry-picking the best ones from different blocks?

“That took a great amount of discipline that I haven’t had since I was maybe 18; to be adjusted and measured about what I’m doing. I haven’t taken that approach in the last five, six years. There was enough going on in my personal life, so it was a ‘fuck it’ kind of attitude. It’s like, ‘Well, I write this much music. So here you go,’ whether you’re ready for it or not, whether it makes sense or not.

“Rock And A Hard Place is the first time I’ve taken a measured approach to finishing an album: thought it through, understood what the sound was, and basically made a proper album. Rather than a handbag full of songs that you’re carelessly throwing out into the world, it’s an actual considered piece of work. As I said, my bad habit is writing too much and ending up almost burnt out and disenfranchised, to the point where I chuck it out and go, ‘Fuck it. Let’s go to the next thing.’”

Your bad habit is probably something that other people would kill for, to be that prolific…

“It’s something you could be envious of. But then I’d be envious of someone who just writes 10 good songs a year, because then they could put that on the album and then go on holiday and relax. I’m sat with a list of 40/50 songs, going through all these horrible meltdowns like, ‘Wait, but what about if this track went there?’ and then, ‘What if the whole album was actually called this?’ Or, ‘But what if I just do that other album?’”

And are you hearing complete songs from the very start? How does the process tend to begin?

“Instrumentation always comes first. I’m a multi-instrumentalist, I play a little bit of everything – a jack of all trades. I sketch out the harmony, the melody, and all the instrumentation, and then listen to the music and see what it feels like it’s talking about. I then find the words within that melody.

“It’s teasing out the meaning from the sound I’m hearing. I’m making what is a totally intuitive and wonderful thing sound incredibly calculated and clinical. There are lots of magical moments, sitting there and letting the ideas waft out of you. I just write really regularly. It’s a sort of structure of my life. Not to aggrandise it too much, but it’s what I do.

“At this point, I’ve realised, it’s my occupation. It’s a job, but it’s a job where you talk about life a lot and about what’s going on… Ultimately, it’s a person writing lyrics and accompanying them with music, which is really quite a basic thing, but it’s amazing when it is actually magical, and that’s what you’re searching for.”

You mentioned California earlier. Did that song signpost both themes and sounds that you wanted to follow over an album, or was it more that it then got you back into the zone?

“It just ticked loads of boxes. It’s a song about a memory of being in Los Angeles with a bunch of buddies – me, my wife and a bunch of friends. I got a big house in the hills with a swimming pool: messing around, drinking, taking some shrooms, having this sun-soaked great time. It was nostalgia, and I felt like the tune really did authentically make me remember the time. It wasn’t a manufactured thing; it actually evoked all the feelings.

“Then, in terms of musicality/the components of the music, it had the right harmony that I was using. The chords and the harmonic gauge of the track had this unique thing. The style of the instrumentation was quite like Stevie Wonder mixed with Ray Charles.

“Again, after I finished, it drove me mad, because I tend to do this thing…. If I write a great or good tune, I then think, ‘Okay, what would a whole album like that sound like?’ Then, that’s what I would commit the next month or two to.”

Is that your prolific nature again?

“I’ve got 15 or so records sitting in my vault that I’ve never released, with names and artwork and everything. I put them on the shelf and, maybe one day, I’ll put them out – whether anybody cares or not, that remains to be seen.

“A lot of writers are probably similar to me, and write a lot of music, but then maybe they don’t go as far as I would in terms of… I have all these finished albums with names that are stowed away. I do definitely have an obsessive personality; I get locked in on something. I get tunnel vision and this mad enthusiasm. It’s funny, when it wears off I just sit there thinking, ‘What the fuck was that?’”

Yellow Days: “For the last five years, I’ve been guilty of being a guy who’s just throwing things around.” Photo: Lewis Vorn

What told you that this was one of the projects that was worth pursuing and releasing?

“In simple terms, it’s the best music I’ve done for a very long time. It has clarity in the music, the articulation. Sometimes you can make something really great – psychedelic music that has an ambience to it, that’s hypnotising, which can be really pleasant. If you do enough of that, you start to be… I quite like to write something that’s not a fog machine, that soothing, intoxicating thing. That can get a little bit old after a while, where you’re like, ‘I just want to hear something spiky and sharp,’ like a window that’s just been cleaned.

“Especially when I started working with these session musicians that played on Leaving Tomorrow, and the other singles we’ve dropped, that was it. It became crystal clear, and the songwriting, the music, and the accompaniment gave this space for the voice, which is so refreshing for me. I’ve been fighting myself and the music to get that space for so long, to get a great tune that I can really sing on.

“Like I said earlier, I would write so much music for other people. Sometimes, the main melody would be too high or too low for my voice. I have these two friends who are singers. I give everything I write in falsetto to this friend of mine called Laura Quinn. Everything I write that’s lower, I give it to this dude called Lex Fransche, who’s my old guitarist who does a solo project.

“It never goes to waste, because they love my songs, and they always take them on and release them. We have a good collaborative relationship, but I basically wrote so much music that didn’t really suit my voice.”

Almost as if you didn’t want to be singing, so you were therefore writing songs you couldn’t sing…

“Exactly. It all became a bit like mistaking my foot for my hand and my arm for my leg. It all got a bit confusing. Am I running away, or can I get back now? It got really topsy-turvy.”

It must feel great that you’ve come back full-voiced and with such clarity?

“It’s kind of a miracle. The stress of having hundreds and hundreds of songs wears you down. I would often say to my wife or a friend or something… I would hit these moments of total disbelief, where I would say, ‘All I need to do is put together a session band, get some tunes and really sing.’

“Yellow Days was caked in layers and layers of neo-soul, psychedelia, and ‘What about this?’ All these what-abouts that weren’t delivering that good feeling. To do an artist project maturely, you have to put down all the toys and focus. If you think about someone like Mac DeMarco, he’s got such a good discipline with his music. When he does a record, it’s so distinctly him. That’s being a proper artist.

“For the last five years, I’ve been guilty of being a guy who’s just throwing things around. Sometimes people would be like, ‘Oh, your new thing was cool. It doesn’t really sound like Yellow Days.’ I was testing people’s patience. You begin to follow an artist because you like that music. When it starts to change, that’s cool as well. But then it changes again and again and it starts to be, ‘I don’t even know what I am listening to at this point.’

“As an artist, you have to be consistent, and you have to arrive at a sound that you’re willing to hold for at least a couple records. Whereas being a songwriter/producer, it was very freeing because you can make any kind of music you like and then you can be like, ‘Hey, today I am this person. Today, I am that person,’ and have a lot of fun with that. You can’t do that with your own albums, otherwise you piss everyone off.”

Returning to your process, does your voice ever inform the words that you’re choosing?

“Yeah. I noticed that I say the words, ‘Oh no,’ about 1,000 times on this last album. It’s a funny thing. I think maybe on this last record, I found my vocal motif, a multitude that you can put in any song that works in every key. Sam Cooke had his, and Al Green’s got his falsetto thing, and Marvin… you know, everybody has one.

“I finally found mine. You can put that in any song and it’ll work, but it revolves around the words, ‘Oh no.’ It’s in every song about six times. Across an album, you’ve heard me say it 100 times. If you look at the lyrics sheet, it’s like a guy falling over, over and over again, bumping his head on the wall.”

And are you someone who knows when a song’s finished, or do you like to keep experimenting?

“I’m totally not a perfectionist at all. I have really short patience with music. I’m very much all about the genesis, the beginning of the songwriting and getting that good. Some songs off this record are really heavily produced, lots of different instruments and sounds and stuff. But I didn’t sit and dial that in for hours. Some people will be like, ‘Yeah, I can tell,’ but that doesn’t bother me.

“I have a thing with songs where it’s almost the opposite of the classic saying, ‘Quality over quantity.’ It’s not in my nature to sit and of finetune music. I get bored, and I want to do something else. I’d rather see my friends or talk about life.

“I’ve done many records with really good mix engineers and producers in the past. Nowadays, I mix my stuff myself. But it was fascinating watching them work away and dialling in these tiny little things. I mean, all power to them, but that’s not me. I’m not lazy, I don’t know what a positive version of that is?”

Maybe your approach is the absolute zenith of capturing the moment?

“Yeah, I don’t know, it’s like there’s more to life than music at that point, let’s go hang out.”

Sharon is one of the singles you’ve released so far. When writing about real people, is it a balance between unfiltered truth and the need to protect the subject?

“That’s a really hard thing to do. The braver you’re being with all that stuff, and the more honest you’re being with all that stuff, the more people like it, even the people in your life that are listening to it. People want to hear someone being honest.

“Over the years, I just got more and more happy and I didn’t want to write songs about like… I’ve seen things online where it’s like, ‘Trying to write a song when I’m in a happy relationship and not doing drugs,’ and then the guy is sitting there, blankly staring at the keyboard. I think it’s important to push yourself to talk about the things that you know, and be brave about that.

“When I first started, I did so much music about my mental health. It resonates so much more when you’re a bit blunter and more honest about what’s going on with you. It’s what music, any kind of creativity, is about – talking about life clearly and honestly. If you’re not doing that, then you’re just having fun with sounds, which is also cool, but it’s not songwriting. Especially nowadays, you’ve got to say what’s going on.”

Do you ever journal or make phone notes to refer back to?

“Really, it’s all about playing instruments. I don’t jot ideas down. I hear music in my head and play it. Also, a lot of the songwriting comes from a love of old records and things like that – trying to think of an interesting sound that you can make.

“Believe In Tomorrow… I think the very beginning of the whole process of that song was like, ‘What if you could take this Stevie-esque chord progression, and give it a bit of a suave, happy-go-lucky, Ray Charles feel?’

“In a lot of cases, what I’m trying to do is explore genre and create really interesting little ear tickles. Then, simultaneously, I’m trying to tap into a sadness or whatever, journal my life into lyrics.”

Using Sharon as an example, would you have heard something in the instrumentation and the sonic world that suggested it was a song about a friendship?

“The tune – the instrumental – is this kind of groovy, night-timey, good time, out-on-the-town sound. Then, lyrically, the whole thing was going outside to a smoking area, in a club or a bar, and chatting to my gal pal about what’s going on in my life.

“Basically, that was the impetus for the song, and that’s a good example. It starts with, ‘Hey, what does this tune feel like to me?’ And it feels like going out in the town and having a good time, but then also the negative spin on it, like, I’m just sat in the smoking area, drunk or whatever, talking like, ‘My life’s rubbish. Everything sucks.’ There’s a groovy tune, but then you’re having a not-so groovy time.

“Sometimes I get a really vague image in my head, almost like a silhouette. Like I said, the smoking area, you can almost see a picture. So that kind of sensory thing that you’re gripping this idea any way you can. And sometimes you can see a little picture in your head whilst you’re doing it.”

And if you’re trying to keep the songs in that same classic soul sound, then it’s gonna lend itself to similar lyrical themes?

“You are what you eat with music. I kind of fell out of touch with all the people, not personally, but in terms of keeping up to date with albums. A lot of my contemporaries, I stopped listening to all the stuff I grew up on. I’d peak every now and then, but I’m not really a fan anymore. I don’t really sit and buy the albums, because little things I used to love about a lot of those people, they’ve all changed, as you do.

“I’m sure lots of people feel that way about me as well. It’s remarkable, really, how much everybody’s changed in my sphere of music. I just listen to Marvin and Stevie and classic records. I think that’s good, but the risk is that you end up making what somebody would call “retro” or “pastiche” music, which is a really irritating paradigm.”

Yellow Days: “My bad habit is writing too much and ending up almost burnt out and disenfranchised.”

How do you avoid that?

“I don’t know, to be honest. A lot of people would say, ‘Oh, man, your music’s very retro,’ and it’s super annoying. Because it’s like, ‘No, I wrote this today.’ I understand, logically, that it sounds a bit like that, but it’s like, ‘No, this is me. I sound that good.’ It does this horrible thing where it undermines the finished products and mix, like somehow I sampled it. I played every instrument on Glitter And Gold, for example.

Do you ever find that when you do check back in with your contemporaries, they’re on a similar journey and making similar choices, the musical equivalent of convergent evolution?

“That happens for sure. A cat like Mndsgn from LA; there are loads of people who are forward-thinking, clever, and great musicians. Sometimes, I’ll check back in and listen, even down to a song title, and I’ll be like, ‘Fuck, I have a song with that title.’ It sometimes makes you wonder if there’s this collective consciousness, that Carl Jung thing, we’re pulling from the same pool, and it’s whoever gets there first.”

People often say to us that songs are floating around in the air like butterflies, and it’s just who can catch them in their net first…

“That’s such a good way to explain it, it’s such a true feeling. But people have started saying it so much that it starts to sound cliché. I heard Paul McCartney say it for the first time, and I was like, ‘That’s so what it’s like,’ but it’s now been overused as a way of describing it.

“But, yeah, it’s the strangest thing when you’re on a really similar wavelength. Putting spiritualism or collective consciousness aside, there’s a logical deduction there that, if you listen to all the same music, you’re bound to end up writing something relatively similar.”

Has the more deliberate process of making this record shown you a new way forward?

“Since finishing the record, I’ve taken a little break from writing. It was all a big, ‘Hurrah,’ kind of moment, but then I came up with this whole idea for a concept album. I have this rock band that we started over the last few years, it’s a side project amongst all the people I write for, called The Stingrays.

“Anyway, I thought of this concept. I won’t tell you what it is, because it’s a little secret, but I started saying to my musician friends, or my wife, that maybe it could be for that band. I could feel the cogs turning, and I’m like, ‘Oh no!’ I was going back into a mad, obsessive spiral. And I was like, ‘No, George, calm down. The concept album can wait.’

“My guitarist Alfred said something to me along the lines of, ‘Why don’t you make the concept record, but wait 10 years. Just chill, there’s no rush.’ And I was like, ‘Okay, that’s good.’ I think he’s figured out how my mind works. He’s like, ‘This dude needs to chill out.’”

So how will you be spending the next few months? Is there a tour on the horizon?

“Yes, we leave for Canada and America at the end of February. I think it starts on the 19th in Mexico, and then two-and-a-half months later, we finish in Glasgow. It’s a heavy run, but I’m looking forward to it.

“We’ve got a seven-piece band with brass and all this kind of stuff, so it’s a real show, which is gonna be cool. We’re really going for a big, Marvin-like extravaganza. It’s gonna be exciting. We’ve got rehearsals soon, so all the work is to come. I’ve written some interesting intros, outros, and salutes for it, which are very much in the vein of I Want You by Marvin Gaye. There’s some really creamy stuff there for everyone to come and check out.”

Related Articles