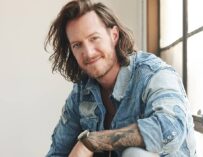

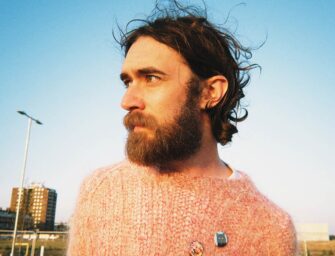

Blair Dunlop: “I don’t want to preach to people, I would rather paint a picture.”

Returning to an unrecognisable scene with his first studio album in half a decade, the singer-songwriter is raring to go

Ever since his 2012 solo debut Blight And Blossom, Blair Dunlop has been a shining light of the UK folk scene. Balancing his virtuoso guitar playing, a voice that carries the hopes of future dreams, and observational songwriting that can be both poetic and perceptive, further albums House Of Jacks, Gilded, and Notes From An Island, demonstrate a maturing songcraft that has earned him widespread recognition, including a prestigious BBC Folk Award, and enabled him to play his songs everywhere from Glastonbury to Palestine.

After a five-year hiatus from the studio, new album Out Of The Rain marks a triumphant return. Exuding a sense of positivity and renewal, Dunlop and producer Jim Moray have created a record that transcends genre boundaries. Infused with influences from both sides of the Atlantic, moments of introspection like Midday Mass sit comfortable alongside road trip anthems such as Let’s Get Out Of The City. Album closer 1989 San Remo Conqueror even affords Dunlop the opportunity to indulge his love of classic cars; imbued with a touching universality, it’s one of many standout moments.

With plenty to catch up, we recently sat down for a chat with Dunlop…

More on songwriting from Blair Dunlop

It’s been a while since Notes From An Island, did you purposely take a step back from writing or have you been working the whole time and it’s only now we get to hear the results?

“I found it really hard to write in lockdown. I was having a bit of a tough time and I don’t even know how much of it was attributable to the COVID situation. It wasn’t helped by that, but I was going through some stuff and couldn’t write. I ended up learning drums, just to do something physical that was also musical.

“I didn’t really have a grasp on where I was at emotionally. I was a bit confused and I couldn’t make sense of it. So I took the time off. I’ve always written in chunks anyway. I’ll have stuff on the go but often I just feel it coming on where I’m like, ‘Well, I’m gonna write songs now.’”

Did having that time off make it hard to come back to writing?

“I used to feel guilty for not writing. And then as I’ve got older… I’ve been pretty prolific. I never thought of myself as prolific because I could write loads more, but when I speak to other people who I would consider to be prolific they’re like, ‘No, you’re really prolific.’ I always did an album every two years. Then also within that, doing various other projects… I actually write quite a lot.

“I also released a live album from Australia [Trails: Queensland (Live)]. I thought I would be too much of a perfectionist to sign-off on a live album, but I was really pleased with it. I was cooking on that tour and it was a great time for me personally, before I had that dip in COVID. It was a nice to put that out for those who wanted an album of just me and a guitar. I delivered that and then it meant, when I was ready, I could make the music that I wanted to make. That’s what I’ve ended up doing with this album. It took me a couple of years to get over that COVID thing but then, after I moved to Bristol, I started writing a bit more.”

Have you noticed the changes in the music industry over that time?

“It’s night and day. Back in the day, I’d put a picture on Instagram every week, do a mail-out and play gigs. Now there’s so much more you have to do, TikTok has changed social media for artists. I accept it. It’s a privilege to do what we do. The landscape is changing and I don’t want to be a middle-aged guy shouting at clouds.

“The UK folk scene is a great scene in so many ways, with so many amazing people in it, but I do feel there’s a sense of entitlement like, ‘We deserve to be heard, and people should pay for that privilege of listening to us.’ I couldn’t agree less with that.

“Back in the day, say 2012, 50 percent of my earnings were from CD sales, and 50 percent of my earnings were from live. Now, if I’m lucky, maybe 10% of my earnings comes from merch, and gig fees haven’t risen with inflation. You have to work so much more to earn the money. But I look at people who are outside of my folk/singer-songwriter bubble and they’re coming up with really creative ways to monetise their own brand.”

Blair Dunlop: “I’m not expecting anyone to hand me a living.”

All of which makes gigging so important…

“I’ve always been very lucky that I play live. I’m a better musician because I was given the opportunity to play live and that really is a privilege. A lot of people come through now make music in a box, on the screen. Absolutely no shade on that, but I’m really lucky that I’ve managed to hone my craft in front of people. I want to be able to do that as much as possible so I can put more money into the branding and the production; build the brand in terms of videos and the story around the music.

“For me, it’s always been the music and words first, and increasingly the production. I’ve never really had a sense for the visuals, but now I’ve been forced to take an interest in that and I’m going with it. I’m not expecting anyone to hand me a living.”

Are you able to separate that from the writing process itself or does the importance of the live scene seep into the songs?

“Weirdly, it used to be more that way. I came through playing folk clubs, I wrote my own songs, I would do some traditional material, but I would very much tailor a set to the audience. When I first started I was insecure about so many things as an artist. I was insecure about my voice, my songs, my guitar-playing, my chat… because of that, I second guessed myself so much. I would be like, ‘Okay, I need another narrative song because there’s too many love songs,’ or if I went and did an inner city gig and was singing these weird folk songs, I’d be like, ‘They don’t want to hear this, they want to hear a pop banger.’

“Added to that, I used to play in loads of different tunings, so I would have three guitars and I’d be getting tangled in my wires. I would be snapping strings going between these crazy tunings.

“Around the fourth album, music became more of a sanctuary. When I started having to deal with stuff in my personal life, being on stage became a bit more of a doddle. Once I’d experienced some relative hardship, relatively, ‘Singing some songs in front of people, I can do that.’”

So you relaxed a bit?

“Also, every time, I would have more songs. Before I knew it, I had about 80 songs at my disposal. If I didn’t want to spend five minutes tuning, because I could see that the people at the front were bored, I could just go into another song. I had more in my arsenal that I could draw from. So it was having the material and the confidence.

“Now I don’t really have a setlist, unless I’m playing with other musicians. I’m a lot freer on stage and I don’t write thinking about what my audience are gonna like. I write because I want to write a song. That’s not to say that is a better way of doing it. I’ve done some writing where I’ve been given a remit, and sometimes you can end up writing something a lot more interesting that’s different to what you normally would do.

“There’s value in that and I’d like to get back to that because I’ve probably been a bit self-indulgent over the last few years. It’s good to freshen it up, but nowadays it comes from me, it doesn’t come from me wondering what the audience are gonna think.”

Do you have a typical process for writing a song?

“I don’t have a process ultimately, but there are certain touchpoints. I do a lot of noodling; I will sit and stare into space and noodle on the guitar or another instrument. I’ve written on piano and wrote a couple of these songs on the mandocello, it’s like a mandolin but down an octave.

“That’s really good because it puts you in a different headspace. I know guitar inside out, then going into another instrument is a bit frustrating because you’re going, ‘Why does this sound crap?’ But that’s great; if you can restrict yourself, it can force you down a road that you’re less comfortable in and then you come up with something different and more interesting. So that’s a good technique, change your instrument.”

Blair Dunlop: “If you can restrict yourself it can force you down a road that you’re less comfortable in and then you come up with something different and more interesting.”

Are there other things you do to help the songs flow?

“I’ll sometimes find or put on a beat. If you’ve got a fragment of stuff and it’s not working, maybe put on a metronome, create a drum loop, or you can find them online/in your software. That’s great to keep you in the zone.

“What I also do is, unless the hook to hang a refrain or a chorus comes to me while I’m writing the lyrics to the verse, I’ll just write like eight verses, and then maybe shift the couplets about. So while I’m in the flow of the verse and in the rhyme scheme and phrasing, I’ll just keep going. I’ll write until I’m totally out of ideas and then go, ‘Actually, I don’t like that. But I like the second half of that. I could stitch that into the first half of the verse.’

“That’s a real time-saver because it stops you flitting about from section to section. And then it’s, ‘All I need now is a refrain, maybe a middle eight or an instrumental break, because I’ve definitely got enough verse there.’ Also, you can repurpose some of the ideas that you’ve written in the verse into the chorus or middle eight. I find that quite an efficient way of working because you really nail the phrasing and melody of the verses in the process. That’s probably my most helpful technique that I use.”

On an observational song like Midday Mass, would that happen in real time with you sat in the cafe making notes or are you always taking things in that then come out later in your songs?

“I’m always taking things in. One of my friends had written a song about a café but it was a totally different kind of song; very impressionistic and abstract. Listening to that song, I used to visualise this cafe back in Chesterfield. The more I thought about it, I was like, ‘Oh, maybe I want to write a song about that place,’ but in a different way, more socially prescriptive and descriptive.

“It was one of those where I took it in and then wrote later. But there is a certain type of socio-political song that I tend towards, and that I’m comfortable in. I don’t want to preach to people, I would rather paint a picture – you’ll probably get where I’m coming from from that picture.

“It’s not a case of not wanting to alienate people. It’s more a case of, I want to paint a picture and then people can take from that what they want. I think it’s a more artistic way of construing a situation that reflects my personality. Every now and then I will pull people up on stuff, but I could go in harder on things.”

There’s being too comfortable but then there’s feeling too uncomfortable with what you’re doing to be able to do it…

“That’s a really good way of putting it. I went to see Billy Bragg the other day, and he’s great at doing it in a different way. I really respect that, but if I did it, it would be disingenuous. That’s not to say that either person is right or wrong.”

Is that how you feel about songwriting in general?

“I did some songwriting workshops down in Kent last year. I really enjoyed it and came to a bit of a realisation during the process of putting together my syllabus… I don’t think there’s a right or wrong way to write songs, and I don’t think there’s such a thing as a good or a bad song. Songs affect people in different ways and there’s a synergy between the performer and the song on any given night that either works or doesn’t.

“It’s about synergy and authenticity, and the connection between the words, the music and the audience. Of course, there is the technical side to it, but I think that’s overblown. It’s more about how the person can move you or convey what they want to convey, and that’s subjective.”

Another song we picked out to talk about is 1989 San Remo Conqueror. What can you tell us about that one?

“That was one that I had to fight for to make the album. I co-wrote it with my drummer Fred. I love vintage cars, and it’s a song about a particular car, a Lancia Delta Integrale. It was the longest-reigning rally champion as a car, and it won five back-to-back World Rally Championships in the late 80s/early 90s. I love it because it looks like a Vauxhall Nova but it’s actually an exquisite piece of engineering.

“I wanted to put the personal into it and I like to anthropomorphise things that I love and see them through the human lens. I also wanted to put a bit of romance into the car and convey my love for it. It’s about the relationship between a father and a son. They go into a garage and the son says, ‘What’s under that tarpaulin?’ Of course, it’s the car, and then the father talks about how they won the San Remo hill climb in 1989 and how he lost friends along the way. In the end, the kid convinces him to see if they can get the car firing again, then they drive off into the sunset.”

We’d also love to know a bit more about the current single, Let’s Get Out Of The City?

“It’s a banger. Jim [Moray, producer] forced me to play it back 20 BPM quicker and it took me ages I was like, ‘I don’t see this.’ And then, towards the end of the mixing process, I was like, ‘You know what, I totally get it.’ He was right.

“I’ll play it a little bit slower live, it’s got a different guitar arrangement. I’ll hybrid-pick the part, palm muting the rhythm and popping out the melodies on the top with my fingers, all in one. We separated them in the studio, did a rhythm track and more of a lead track. So we deconstructed it and then put it back together in separate parts on the album, which is a process that I like. I really like playing that one live because it’s all self contained in my right hand and it really feels good to play, and the chorus bangs.”

What can you tell us about the subject matter?

“Again, it’s painting a picture. I love London, but it’s that thing of getting to the end of your tether. It’s tied in with themes of freedom and lockdown, getting away from it all. It’s got that detailed verse talking about all of the vices of our capital city and then the chorus is just like, bang, ‘Let’s get out of the city.’

“I enjoy songs that know where to be detailed and where to be economical. That marriage of having a descriptive verse and then a simple refrain that everyone can get behind. A lot of songs that I’ve enjoyed over the last few years have managed to capture that, like Bright Star by Anaïs Mitchell.”

You mentioned Jim Moray’s involvement, what was it like to working with him?

“He’s a bit of a legend because he was doing what Fairport [Convention] and that crew were doing in the 60s, but forty years later. Listening to Jim was the first time that I heard traditional songs fused with elements of electronic music, grime, pop and stuff like that. It took actually watching Jim play for me to really get into trad-folk. The folk-rock world that I grew up in sat aside from that.

“I got heavily into trad-folk in my late teens through artists like Jim Moray – he was probably my favourite artist at that time. Everything that he said was gospel for me at that age. I remember him tweeting about going to a Kathleen Edwards gig, she’s a Canadian singer-songwriter. I knew that Jim was into experimental stuff and he was really forward thinking. Kathleen Edwards was right up my street, but in a different way, just really well-produced country rock/Americana. She then became a massive hero of mine and I got further entrenched into that side of things.”

What impact did that have on the album?

“I initially thought that I was gonna move back into folk; I was ready to make more of an acoustic record. But the songs that I’d written over lockdown, they didn’t really suit it. Working with Jim reinvigorated my love of that kind of stuff, the classic North American singer-songwriter stuff, and it ended up being in that vein.

“Ironically, going to someone who is so influential in the folk world, I’ve come out with an album that’s not as folky – but there’s a cyclical aspect to it because through him I got into Kathleen Edwards and even more into adjacent artists like Jackson Browne and Warren Zevon. So it was really great to work with Jim, he understands all of my influences. Ultimately, when we got into a room together, we had a really nice synergy.”

Blair Dunlop: “I like to anthropomorphise things that I love and see them through the human lens.”

The first thing you hear on the album is a programmed beat on Ain’t No Harm, was that an intentional statement to start the album with?

“When I first started working with Jim, my idea was to have a string quartet around me. I was listening to a great band called Crooked Still; I’ve toured with their singer Aoife O’Donovan, who’s brilliant – she’s such a big hero of mine. They champion bluegrass instrumentation and have an amazing cellist who plays this choppy percussive stuff.

“There’s a guy in Glasgow who can do that, Graham Coe. He’s amazing, he’s on the album actually. On the first track I was going to do an English version of Crooked Still. Then when I got in a room with Jim and we played through the songs, it was clear to me that it only seemed to serve the songs in a certain way. The album just lends itself to how it turned out.”

Is it important to go where the songs want to go?

“What’s been really nice about this album is that I came in with that perception, and then parked it at the door and thought, ‘That will be cool in the future, but for this album I’m just gonna make the album that I want to make.’ There are elements of acoustic stuff, when it needs it, but I wasn’t going to force myself to slow down purely because I’d had this idea. Previously, I would have been wedded to an ideology or worried about what the scene might think of me

“So Jim came up with the programmed beat and I loved it. I love hip hop and so many kinds of music. I love that the borders are coming down between genres. He played that programmed beat and then I put the guitar down to it. I struggled with the beat itself for a while. It wasn’t the fact that it was programmed, I loved that aspect of it, it was purely where the emphasis on the rhythm was because it was affecting my right hand on the guitar and how I was phrasing the song.

“I like how it’s a bit of a statement and as the song says, ‘There ain’t no harm in trying something new,’ and that’s true. It’s a nice marriage of the acoustic and the non-acoustic and probably the archetypal Jim Moray stamp on the record. It’s that marriage of the old and the new and it feels good.”

We’re speaking to you at the point before the album is out and you’re heading out on tour. Are you impatient for people to hear the songs?

“I just want people to hear them. It’s so good to be doing it again. I’m very privileged in that I’ve always played live, that is my home and where I feel comfortable. It’s been so long since I’ve had new material that I can play in front of people.

“I want the songs to be heard so that I can just do it again. What’s great is that the songs now give this tour life. And then another tour; go into other territories like Canada and Australia. Hopefully these songs are my ticket back there. Then while I’m there, I’ll pick up inspiration, watch other people and go, ‘Just when I thought I was getting bored of music I’ve seen something that I love and I want to write again.’ So that’ll feed the cycle. It’s just great to be back on the hamster wheel.”

Out Of The Rain by Blair Dunlop is released on 24 May via Gilded Wing Records and Dunlop is currently on tour across the UK. To pre-order the album and find the latest tour dates, head to blairdunlop.com

More on songwriting from Blair Dunlop

![Interview: Jessie Jo Dillon [2025]](https://www.songwritingmagazine.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/jessie-jo-dillon-2-by-libby-danforth-335x256.jpg)

Related Articles