John Waite: “I only really write when I’m confronted with something in my life.”

We catch up with the ‘Missing You’ songwriter to discuss his long and varied career and new anthology of recordings

As an accomplished singer-songwriter who never settles for less than artistic authenticity, John Waite has had a steady sequence of music releases which have connected to audiences worldwide throughout his career of over 45 years. As a teenager, Waite gravitated towards the arts and – studying at Lancaster Art College – found that music was the avenue to his greatest creative expression. Early success with rock group, The Babys, led Waite to a solo career, the No 1 single Missing You and albums like 1984’s No Brakes, 1995’s Temple Bar, and 2011’s Rough & Tumble. Success also came with supergroup Bad English, with whom Waite served as lead singer and bass player for four years.

In March, Waite released Wooden Heart Acoustic Anthology the Complete Recordings: Volumes 1, 2, and 3. The acoustic collection shows Waite in his most natural state: as a performer with pure, honest and impactful musical abilities.

Our first time speaking to Waite since an initial interview in 2013, here he reflects on his career journey, discusses his love for acoustic music and his Wooden Heart albums.

When did you first start connecting deeply to music in your life?

“Since I was a kid, it was always in the background. There was Western music on the American Western TV shows, which I responded to very quickly. It was kind of the nearest thing to rock n roll. And I just picked up whatever I could, wherever I could…My cousin Michael had a guitar, my brother Joe became a guitar player when he was about 11 and my mom played the piano. The whole thing was very organic. It was just entertainment.

“And by the time I reached maybe eight or nine, after listening to all this cowboy music, The Beatles came along and that just smashed everything. When it struck, it struck overnight and everything changed almost within about a month. All the music that you could imagine, from skiffle to jazz to pop to to rock n roll, suddenly just existed right in front of your eyes. It just came into being and I was nine, so it changed my life completely at nine.”

What was your personality like as a kid?

“I was very shy. I really was cripplingly shy most of my young life. We didn’t have anything, so we made a lot of nothing. You could get a bottle of pop on a summer afternoon when you were playing in a cornfield somewhere, and it was a very, very big deal. And all you got was a T-shirt that had a cowboy on it, and it would be the biggest thing in the world. We had really nothing.

“We had an outside toilet and we lived in the countryside in a cottage and across the road was this gigantic, huge park on the highest point of my hometown. There was just a tremendous sort of palace like the Taj Mahal built in the middle by this industrialist for the common people, and it was all lands and trees and monuments. It was fantastic to live there. And then if you looked to your right, it was just cornfields going down into a valley. So I was raised climbing trees and it was great. I think I had a pretty idyllic childhood, but I was incredibly shy. I remember just being embarrassed being in a crowd.”

Kids go through that phase sometimes, though. That’s normal…

“You have to learn. So when I became a singer in The Babys and when I was writing the songs, I had to go, ‘Well, what are you going to do? This is what you long to do. This is what you are. There’s no point in being coy.’ And I wasn’t coy. The art came first. It wasn’t about promoting myself. It was: It should be like this. This is how I understand it to be…So it wasn’t like I was really having to deal with the shyness as much as writing the songs and singing.”

Tell us about your time in art school and studying to become a painter?

“Well, by the time I reached 15, I was just reading books and painting. I couldn’t do anything else. I was a popular kid, but I didn’t have an academic side to me, apart from the books. I always loved to read. Everything else, like history, which I loved, I couldn’t take it in. I was dyslexic…So they gave me a year just to put together a portfolio at school for the interview for art school, and I got into art school. It was the biggest thing that ever happened to me. All I ever wanted to do was paint.”

When did you realize that music would be what you pursued professionally?

“When I was at art school, I started to play in a band and we actually played a few art school dances. The next thing I knew, at the end of the four years I got a diploma and it was like, ‘Now what do you do?’ There’s no jobs for painters. I realized I was never going to set the world on fire by painting and drawing and I had this thing for music and I thought, ‘Even if I’m not great, it’s going to be more original if I pursue music.’ And so I turned my attention to that.”

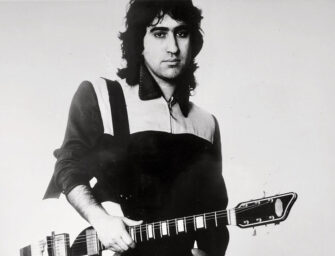

John Waite on 2013’s Live-All Access album, which coincided with our last interview and talked about how he wrote Missing You

What was the turning point that started off your career in music?

“After being around my hometown for a year or so, I actually got accused of a jewel robbery. The police were trying to crack down on the scene that was going on, and they arrived one day at sound check when we were just getting the guitars in tune and took us all into the police station and tried to put the fear of God into us. I was just a bass player in a band, but they came to me, and I left.

“About two weeks later, I got the offer of a job to go to London to play bass in a jazz rock group called England. I left, but I left primarily because it looked like they were seriously going to take an interest in me, and a couple of my friends had already been to court and it was ruthless. They were coming to really clean up the city. And it was a very mild scene. It was university students and art school students just being kids, but they really came in with a hammer and they made me look like I was at the center of it, so I left and my life just took off. I went to London and everything changed.”

How did you develop your songwriting ability and gain the courage to be so vulnerable in your lyrics?

“Well, it’s a mystery. People who talk about songwriting as being a profession, it’s admirable. Holly Knight, Diane Warren, people who are just gifted songwriters that bang out songs like that are incredible. I didn’t want to write singles to begin with, but I had this thing, when I heard something go by, a piece of music, it really moved me. If somebody was being confrontational or really digging deep to say something, I responded to that and I tried to mirror that in my life so that it had authenticity.”

What sparks your inspiration to write music?

“I only really write when I’m confronted with something in my life. I don’t write for kicks. It’s not like I sit down and try and write a song for somebody. The album Temple Bar, that was all about turning 40. It was sex, drugs, and rock and roll, but it was in a more everyday way. It was about New York City and spirituality and kind of asking those big questions in midlife, but I set that to music.

“My process is just, hit a G chord and start singing. I tend to bounce off people. It’s great to work with a guitar player, somebody who knows a little about how to shape notes in a different way, [use] voice chords, and that will open up something in my head that I just step through if I have a title or an idea.

“Downtown was pretty dark and it was about New York City and Sunset and all the memories and all the people that I knew, and that was the beginning of something completely different. But, I think after Bad English, I really wanted to write mature stuff. I think the production was so gigantic and everybody’s playing at once. And my roots are in kind of country and western, folk, blues, and just straight ahead pop…But I don’t listen to anything light, I like things that are lyrical.”

What were your early days in New York like, prior to releasing No Brakes?

“Well, the day after John Lennon got shot, I tripped up on stage and tore all my cartilage, and that was the end of The Babys. I went to hospital to get my knee put right and I was in Lenox Hill Hospital for four days. Then my manager said, ‘Do you want to stay at my apartment while you get yourself together and book a flight back home?’

“So I was on the West Side around 17th Street and Broadway, and this guy from the record company…took me to some clubs. I was on crutches, but he walked me around and showed me New York, and I’d never been there by myself. I was always passing through with a band or doing interviews or TV. And I had time to look at the city and reflect and just feel it. And I just suddenly realized I was home.

“New York is just a profoundly interesting city with seasons and great architecture and people that have a higher level of energy and creativity. They’re all trying to win. So it’s a wonderful place to be and write music and I think I’ve probably written all the best songs I’ve come up with in New York.”

John Waite: “The simplest things in life are the most truthful and honest.”

Then, in ‘84, you released Missing You and achieved international success, what stands out to you about that time in your life?

“I went over to L.A. to sign contracts and meet the record company, EMI. They were really wonderful people, very eccentric and knew music. It was like waking up from a dream to be around people that were that gifted, and I got introduced to a guitar player and we just started making the record. I’d gone over for a week and stayed for three months and made the record. It was that quick. And overnight when it got released it was No 1, and that was weird…not being able to walk into a bar and have a beer at two in the morning and just watch a band or something.

“I didn’t respond to that very well. It seemed people wanted to shape who I was, and I was always kind of defiant about where I was going. I didn’t follow the rule book and it was uncomfortable. I think looking back on it, I pushed back big time on fame and tried to create a niche where I could just write and create and have a really crack band and just be an artist.

“I didn’t want necessarily to be a famous artist. It was enough that I’d been No 1. I felt like I had checked a box and I was going to be allowed from that point to do whatever I wanted to do without swimming upstream. But it was hard to disentangle from the machine that wants you to make giant amounts of money and be a star for the sake of being a star. And you’re creating music that isn’t necessarily heartfelt music or original or anything, just to make money. It’s a trap of success. That’s what fame is. You suddenly stop being a musician, you start becoming famous.”

You’ve had experiences with groups as a member of The Babys and Bad English, and have done a lot of solo work too. How do the two experiences compare, being in a band versus working solo?

“Well, if you’ve got a really great idea and you see it in a pure way, nothing turns out like the first moment of inspiration. I paint still. And when you visualize a painting, it never comes out like you think it’s going to but in a band, it’s more difficult because the instrumentalists have their own way of playing something. Or if they’re writers, they’re trying to put their thumbprint on it. And what might have been a really tremendous idea going in can be brutalized, and sometimes it’s enhanced and it’s wonderful, but it’s like rolling the dice. You just don’t know where you are going to get when you’re in a room full of people. But my band in New York that made Temple Bar And When You Were Mine, that was an incredibly gifted band [with] Jeff Golub on guitar and Shane Fontayne, [and] Tony Beard on drums.”

How would you describe Wooden Heart’s style and sound?

“I think… it’s absolutely pure. It’s just the most simple way of putting the song across, but in a very experienced way. It’s all the experience of all the years I’ve spent writing songs and touring and playing, but it’s distilled into this thing that’s just acoustic music that sometimes turns a left corner.

“It’s got a shading with electric instruments, sometimes a percussion, but it’s fundamentally extremely spartan…the simplicity of it on that level is just so enjoyable because it’s the choice of words. It’s not like embroidering something and going over the top and trying to sound smart. Great songwriting should be like that. It shouldn’t use words of more than three syllables. Some people try to sound smart, but you don’t talk to people like that. “I love you” is just “I love you.” Maybe sometimes it’s great to expand on that, and it’s Romeo And Juliet, but I think the simplest things in life are the most truthful and honest. And I think that translates to songwriting and writing in general.”

What was the process like this time around?

“With lockdown, I was kind of climbing the walls at some point. I couldn’t tour. I expected to write and I just had writer’s block because there was no energy out there. Everybody’s kind of in a subdued place and it just really affects everybody. I had already recorded volume one and two of Wooden Heart. I’d actually gone in the studio to record an electric album and, every time the guitar kicked in, I felt like I’d heard it before. It all just seemed like I’d been there.

“So I turned my attention to acoustic music again. I thought, ‘Well why don’t you just keep going with Wooden Heart?’ And I set out to record as many songs as I could with Shane [Fontayne] on guitar and Luis Maldonado from Train and I managed to cut five songs and kill two songs that were acoustic from previous albums, and I had enough for volume three. So I just released them all together. But it was interesting. I did a painting for the cover, a self-portrait. It was all home-grown.”

Do you have any future plans for projects musically or any other creative endeavors you want to pursue next?

“Well, I’m painting at the moment,…but in the studio with the acoustic stuff, that might be the end of it. And…what I was thinking of, it’s not so much the music, it’s the instrumentation. I think I want to play with acoustic instruments. I’ve been listening to some jazz music recently, and you can’t help but be taken with the simplicity of the instruments and you’re completely focused on the sound.

“If somebody’s singing, you’re listening to the singing, and the more raw it is, the more engaging it is. So I think I’ve always loved life performance. I think the first take is always the best and the last stop in music is to sort of bring it around again in a really exposed way in performance. And that’s where I’m going to go I think. I think it might be that I’m just done with electric music.”

INTERVIEW: DEVIN HERENDA

Related Articles