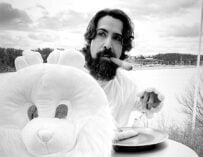

Niclas Molinder: “I became a chef – that was the closest to creation I could come!”

How the Swedish producer-songwriter went from being a chef to founding a tech company with Max Martin and ABBA’s Björn

Since the release of his first track in 1994, Niclas Molinder has found success as a songwriter, producer, music publisher and engineer, but has risen to prominence in recent years as a pioneering music tech entrepreneur. Previously launched under the name Auddly in 2012, Niclas founded the world’s first music-credits ecosystem with ABBA legend Björn Ulvaeus and pop hitmaker Max Martin. In 2019, the three Swedes relaunched the company as Session, with a free app for music creators to capture and verify vital song metadata, and are on a mission to ensure those creators all get the credit they deserve.

Hearing the news that Session had received financial backing from Spotify and YouTube, we caught up with Niclas to hear about his remarkable journey from remixing tracks in the 90s through to starting a publishing company and spotting the business opportunity that led to having lunch with Björn…

Click here for more interviews

Taking a look at your discography, the first writing credit I see is with the 12-inch single Yammy by Da Kooja. What was the story behind that?

“I’ve always been into music and I’m so glad that kids today have much better opportunities to learn about music, whether that is playing an instrument or learning more about the industry. When I was a teenager, there was nothing. I don’t think I’m a particularly good musician, I don’t really read scores, you know, I just hear things in my head. So I became a chef – that was the closest I could get to creating something! So even though I was convinced that my life was going to be in music, I took a side path for a couple of years and became a chef. I really enjoyed it, actually, but after a couple of years, I realised that it wasn’t going to work and I needed to focus on where my real passion and dreams were – music.

“Initially, I thought the only way to really get into the industry was to become an artist and to be on stage. But I soon realised that everything happens in the studio. I managed to secure a job as an intern and that’s where I found out I was most comfortable at, in the studio, producing and recording. It wasn’t so much writing music back then. I come from an electronic background, so back in the 80s I was listening to Alphaville, Howard Jones, Depeche Mode and all that kind of stuff. In one recording session, I was recording with a heavy metal band, like really hard rockers – [we were from] completely two different backgrounds – but the guitar player and I really clicked and we started talking about things. It turns out that guy is Joacim [Persson], who I ended up running Redfly Music with. And the band we recorded were signed to Roadrunner Records in Holland. Even though he was into heavy metal and I was a synth guy, we had house music as our common interest. I don’t remember the details, but through Roadrunner Records he managed to get the vocals for a song called Da Kooja and we were asked if we could do a remix. We had no idea what we did, but a year or two ago I found an old DAT player and I actually found that mix! It’s so long ago, but I think the story was that we did it and sent it down to them and a couple of weeks later they called and were super excited. So they chose our version as the main version for the project, instead of a remix. And I think the song became a No 1 on the Dutch dance chart. So actually Da Kooja is the reason why we continued doing what we did for so many years. So it was a coincidence that was so important for our careers, actually.”

Can you recall the moment when you started doing more songwriting?

“Yeah, Joacim came from a background of playing in a band and I had previously been in bands and dreamt of becoming an artist, so songwriting was nothing new to us. We’d both done that for so many years. But when we got into the studio – and back then the house music and remixes were so common – the songwriting actually fell behind a bit. Also, we got more and more into the business and the industry, and as the producer, many times the labels and the artists also asked for songs. So, for us, it was natural to just start writing songs again. There’s that combination where you’re more or less creating a project as a producer: you wrote the songs, you recorded everything and you pitched it to a label. So that’s how we started, we found a couple of really good, talented artists and we created a whole project and started pitching that. Once we did that we got into the labels and they thought we were talented songwriters and producers. So thanks to that, we also got other jobs. It all happened very naturally, I must say.”

And was it at that point that you met Max Martin and started sort of collaborating with other Swedish production teams?

“No, but Sweden is a pretty small country when it comes to that, you know, everyone knows about each other. And I mean, Max was huge already back then. But there was a Swedish artist called Camilla Brinck [we worked with] and, through Virgin, we did one of her songs together with one of the Cheiron [the production studio founded by Denniz PoP and Max Martin] guys. So that was the first contact we had with Max, but I used that much later on when we started Session together, because if I didn’t know him before it would have been so much harder.”

Niclas Molinder: “Creators don’t give a shit about admin, except for a couple of times a year when their royalty statement comes.”

Although it was called Auddly back then. When did you start that company, what led you to rebrand as Session and what’s different about it now?

“It is exactly the same thing. So there I was with Joacim, my partner, we were pretty successful, we were doing great. But we had so many requests, we couldn’t really keep up delivering, so we decided to start a publishing company and became a production house, more or less. It was Joacim and myself and then we had three really talented, up-and-coming creators signed to us – they were out in the world, writing songs and producing music. I was so naive that I thought I could run a publishing company and a production house with my right hand, and still be in the studio writing music! But so much of my time was chasing data constantly and I realised how dark and deep the black hole of metadata is, and how complicated the music industry has made it for itself. I mean, it was impossible.

“One trigger point was when two of my writers came back from New York. They were there for a couple of weeks writing songs. You know how it is, when you’re there working, you bump into someone and they say, ‘Hey we should write a song!’. Well, they actually met someone, they wrote a song and it was great. But when they came back to me, I said, ‘Okay, give me all the information so I can do all the registration and make sure that everything is in order. Who did you write it with?’ And they said, ‘DJ Pete’ and I was like, ‘Okay, do we have anything more details than DJ Pete?’ And they’re like, ‘No!’. It took me weeks to find out who this dude was. That was when I realised that we needed to do something here and I needed a tool for my business. However, I didn’t find anything that could cater for this, so that’s when I decided to build what was originally called Auddly.

“Auddly is a weird name, but back then every tech company needed a .com domain, and they were all taken, so we [had to] take what was available. Auddly actually stands for audio and lyrics. It worked pretty well here in Europe but when we got to the States, the name didn’t really fit, so we decided to change the name. That was also when we relocated to London, so we rebranded in 2019 but it’s exactly the same service.

“I realised that a publisher, manager, label, PR, or any stakeholder needs the information to be able to pay and credit songwriters, so they need to have the correct data about what happened – the truth about who did what, where, and when. Creators don’t give a shit about admin, except for a couple of times a year when their royalty statement comes in. We solve so many other problems in life with technology, so why not solve this as well and let the creators just create music? As a publisher and a songwriter myself, I realised that the ‘identifiers’ are so important for individual music creators out there. If you don’t know your identifiers, it’s like going to the bank without your social security number and thinking you’re going to be able to withdraw cash – it’s not going to work. You need to use your identifiers and know what the identifiers stand for. As creators, we call ourselves names, of course, but when you write a song together now and only use our names, we’re going to run into a problem because I have letters in my full legal name that you don’t even have on your keyboard! How are you going to be able to register me? You can’t. Therefore, identifiers are everything for songwriters and for performers.

“So that was the whole idea with [what is now called] Session. Just identify you as a creator and when you do something on a song, even if it’s on the songwriter side or on the recording production side, we capture the information for you and send that downstream so that you get credited and paid when the music is used. Simple as that!”

Why do you think that the software developers of DAWs haven’t catered for this need?

“I mean, I’m a producer so I’m here in front of a DAW, all day long… So that was one of the first things I had in mind when I started this, that we need to be on the DAW. But it took me years to just get in touch with the right people on the DAW developers. And the first one that was so supportive and really wanted to learn was Avid and Pro Tools. But when I started talking to them, they didn’t really think that they were involved in the data management side of things. I said, ‘Oh, you are!’ I mean, we have been having a great collaboration with Avid and I just think there was a lack of understanding. Session is actually software that runs on your computer that listens for when a DAW is launched… So you can easily access the information or add information – you don’t have to install a plugin or you can work between different DAWs, as the information is synced between them. It’s done in the background.”

Niclas Molinder (centre) with the other founders of Session, Björn Ulvaeus (left) and Max Martin: “[Max] said it would be so cool to have Björn. And so I tried to get hold of him for such a long time.”

So what do you think songwriters need to know, in terms of their metadata?

“It’s just one thing: identify yourself. Make sure that you identify yourself and you get linked to the song that you write. Today, the average number of songwriters on a new song is five, so when you start working with people the important thing is that you identify yourself and you have exactly the same opinion about the song as the other parties. And when I say the same opinion, I mean do you refer to it as the same title? ‘I Love You’ can be spelt in many different ways and if you have different spellings, that’s going to cause problems later on. So identify yourself and make sure that you have exactly the same opinion about everything. Splits is something that comes up all the time and we know that songwriters aren’t always comfortable talking about the splits, but it’s okay to do that later as long as you know who the others are. Then we can identify everyone and go back and say, ‘Hey, now we have money here, let’s agree on the split.’

“So it’s important that you identify yourself and, if you want to earn anything from songwriting, you need to become a member of a copyright society, because then you get your international songwriter number which is called IPI. And that IPI number is the most important thing for you as a songwriter, and you need to link that to the song. To make it a bit more complicated, each song needs an identifier as well, because there are so many songs that have the same titles. So if you put a song out to the market, even if you write it 100% yourself or if you collaborate with others, it’s so important that the song you write gets an ISWC (International Standard Musical Work Code) because if you don’t have that, you will not receive any money either. That’s the most important thing for you as a songwriter from a rights management perspective, then it’s of course important to write a good song because if the song isn’t good no one will listen to it anyway!”

Do you know of any stories that illustrate the importance of this data?

“Yeah, I can tell you one thing that happened recently, actually. As I said, when you write a song it’s so important that you link yourself to this unique musical works code. And there should be only one code, otherwise there’s going to be confusion and misunderstandings and disputes. But it’s really hard to keep track of all this and this even applies to the biggest artists I’ve worked with. Take ABBA and Dancing Queen, for example, because that is also WC 1 – it was the first song ever that received an ISWC. It’s one of the most well-known pop songs on the planet, and it should have only one ISWC. But it turns out that when we checked a few months ago, it had 87 different ISWCs! If a huge band like ABBA have these problems, believe me, there are so many others that also have multiple identifiers. And, if that happens to you, there will be problems with payments. So make sure that you identify yourself and link it and keep track of it. Make sure you don’t have 87 of them because that’s not good!”

How did you meet ABBA’s Björn Ulvaeus?

“At the Tate Modern in London. Max was already a partner of the company and we said that we should have someone else. I realised that none of the larger music companies and the industry as a whole would really listen to me in regards to changing their behaviour when it comes to data management – I needed power, and power in this case is very high-level profile music creators. So Max was there and we said it would be so cool to have Björn. And so I tried to get hold of him for such a long time. I just had a couple of ABBA admin email addresses and I emailed, and emailed, and emailed… And after a couple of months, I just got an email back that said, ‘No, sorry, he’s not interested, so good luck.’ But by then I’d been pretty active pitching my idea and I pitched it to STIM [the Swedish performing rights organisation] who said they were going to have an event in London, where ABBA was celebrating their 40 years anniversary, and they wanted to highlight Swedish tech companies that want to improve the music industry, and Bjorn Ulvaeus will be in the audience. They said, ‘Niclas, would you like to come and pitch your idea?’ Yes, you bet! So we were one of five companies pitching our ideas from the stage. [At the end] the moderator goes, ‘Björn has to run, but can the companies just come up on stage and we can take a photo of you all together?’ So I ran up on stage and stood next to Björn, they took the photo, and then he turned to me and said, ‘Thank you, Niclas. I like your ideas. Do you want to have lunch with me next week?’ So we had lunch and he decided to join, and he’s been an excellent mentor and friend since.”

Related Articles