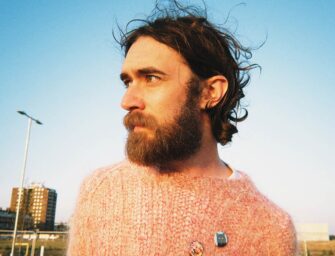

Mike Stock: “I’d already started thinking about the business side: you put on a show, you act and you play a part”

Reflecting on life in Stock Aitken Waterman, ‘one of the most successful songwriters of all time’ shares some hit-crafting tactics

Margate-born songwriter, record producer and musician, Mike Stock, became a household name under the banner Stock Aitken Waterman in the 80s. The trio achieved their first UK No 1 in 1985 with You Spin Me Round (Like a Record) for Dead Or Alive, and went on to become one of the most successful songwriting and producing partnerships of all time, scoring more than 100 UK Top 40 hits and selling 40 million records. To date, Mike has written a total of 54 UK Top 10 singles with the likes of Kylie Minogue, Cliff Richard, Rick Astley, Bananarama, Donna Summer, Steps, Mel & Kim, Sinitta and Jason Donovan.

Recognised by the Guinness Book Of Records as one of the most successful songwriters of all time, Mike holds the record for the most No 1s with different acts, after creating chart-topping hits for 11 separate artists. He also became the first person to receive the Ivor Novello Award for Songwriter Of The Year three times in a row between 1988 and 1990.

After hearing he’d recently teamed up with Bucks Fizz (now known as The Fizz) to co-write and produce their first album in 31 years, we decided to catch up with Mike and see how his approach might have changed over the years.

Give us a bit of background in terms of when you discovered the art of songwriting.

“I do recall starting songwriting when I was very young – I was about seven years old. I kept a little folder of my ditties, which my mum stored away – I’m not sure where she put it and she died a few years ago – but I illustrated my songs. I remember seeing a particular black and white film, about Tin Pan Alley and about songwriters writing a song a day. I remember the man who wrote Any Umbrellas sold it for half a dollar, or something, and I remember thinking: what a fascinating idea.

“There was music in my house anyway: my older brother is a classical musician – played German national opera all of his working life – my father played the piano and my mum sung a bit, but not professionally. I was always in the school choir and on stage in the school productions, so I suppose I must’ve had some kind of hankering for that thing, when I was very young.

Who or what inspired you, musically, at that point?

“I always thought songs had writers and songs had singers. The Beatles hit the ground running and suddenly that all changed a bit. And I think you can make an argument for and against that. In a way, The Beatles moved on to the credibility factor of writing your own songs and singing them yourself. As opposed to the Frank Sinatra idea where you have a manager who says, ‘It doesn’t matter who’s written them, but I’m going to find you the best material,’ rather than saying to Frank, ‘I know you don’t really write, but perhaps you could come up with a few ideas yourself.’ Elvis didn’t do that. The biggest singers in the world don’t do that, apart from when The Beatles happened. Suddenly you get Paul McCartney who’s a great singer and a great writer, and like I say, I think the jury’s out whether that’s for the better or worse.

Did you play in a band?

“I formed bands in my teenage years. I went to university and backed out of that after two years because I couldn’t take it anymore, and I went out on my own into pubs and clubs with a guitar, but I was singing classic songs. I have a sort of encyclopedia in my head of all the brilliant writers of the American songbook as well as the British stuff. I’d go out and play dinners and do Irving Berlin or some Cole Porter, or whatever. When I formed a band it gradually evolved and I started to include some songs that I’d written. I had two bands with the same personnel, but with different names: one to play disco hits at hotels, weddings, bar mitzvahs and all that, and the other would play the rock venues, pubs and clubs, where you did your original material. We’d wear suits and ties in one and jeans and t-shirts in the other. Because they’re two different ideas, in the hotels my band got £500 a night and in the pub we got enough for a beef burger! I had to change the name because I didn’t want somebody in Park Lane walking around the corner and seeing me in The Golden Lion playing for no money, then we try charging them £500 the next night for a wedding. So I’d already started thinking about the business side: you put on a show, you act and you play a part.

Mike Stock, Matt Aitken and Pete Waterman (left to right) clutching their haul of Ivor Novello Awards

“Finally, at the end of 1983, I decided we were quite good at the band thing and thought I could carry on earning a living until I retired. But I thought, no I’m going to stop this and go in the studio I’d built under my house and develop production ideas and my own songs, and see how far we can get. The rest of the band all left, apart from Matt Aitken who was the guitarist, and he came with me to see what we could do.”

Where were you at this point?

“I lived in Blackheath, so I was gigging all over London. I then moved to Abbey Wood where I had a bungalow that was built six feet in the air because of the Thames flooding, and under that I could put my studio. That’s where I was when I made the decision not to do that band. I made good money from the gigs, but it was really just a safety net to my real passion, which was to write and produce my own music.”

Had a forged a strong partnership with Matt by then?

“Well, he was living with me, with my wife and kids – in the basement – because he didn’t have anywhere to stay. At night we were doing the gigs, but during the day we were in the studio, honing down any ideas and I thought we had a possibility of making it – he was a great guitarist and a good foil when you’re sitting there writing songs. But we took a risk. Suddenly we were walking out over that cliff edge and you don’t know what you’re going to step into.”

What was the next turning point that led to the formation of SAW?

“That was New Year’s Eve, so on the 1 January 1984 we get down the studio, Matt and me, and we came up with this idea to do a female version of Frankie Goes To Hollywood. On 16 January, Matt and I took the idea to Peter Waterman – he was third on the list, actually, as we’d gone to Red Bus and RAK, but the A&R men weren’t there! I knew Pete because I’d touted some of my songs around before and he’d picked up one of them and producer it with someone called Pete Collins. So he was one of the appointments I made that day, and he wasn’t there either! But his girl there said he’d be back at two o’clock so Matt and I had a coffee or a cup of tea and went back to see him. Of course, Pete understood there wasn’t actually a band – we’d got a couple of girls in to front it and invented the name Agents Aren’t Aeroplanes – so we could tell him the vision and he got it immediately. We went in the Marquee studio a few weeks later and recorded it. That’s where I suddenly fell in love with high-tech studio equipment. I discovered drum computers and sampling machines that were in their infancy, but a great asset in the studio.

When you went to Pete with the idea, did you have any songs written already?

“Yeah, we only went with one song, which was called The Upstroke – it was sort of an invention of ours to do a new dance. There was a thing going around at the time by The Sloane Rangers to do with ‘Sloaning’ and they had a little dance to go with it. It was a commercial idea and a bit naff, to be honest, but Pete understood it and so that’s the song that we went with in the studio and refined it. We hadn’t really thought of it being so high energy, but that was what was going around at the time, and that was what got released. It was the first recording we did, so it wasn’t going to stop the world! But it got us started.

“The very next thing we did was Divine, You Think You’re A Man by Geoff Deane, and the next song was one we’d written – Hazell Dean, Whatever I Do (Wherever I Go) – which became a Top 5 hit and a hit all over the world. That was originally written by Matt and me, back in the studio in Abbey Wood, and we gave it to Hazell.”

Mike Stock: “I would prefer to find an artist and write based on what I knew about them, so I feed off who they are”

How did the dynamic of the three of you develop over those first few years?

“From my point of view, Pete’s position was kind of like a ‘fixer’; he had an address book and knew where things were; he had contacts with people. After we’d done Hazell, Pete Burns of Dead Or Alive heard it on the radio, came to us and said, ‘Could you make his record?’ So we start work on that in the Marquee and we didn’t know it but in September we were recording You Spin Me Round, which was Pete Burns’ song. So we didn’t write that but it became our first No 1 because it picked up on the Hi-NRG vibe we were doing with Hazell.

“But, running parallel to that, I had sensibilities as a writer that meant I didn’t have to stick with one genre. So while the recording of their album was going on, I was doing work with a girl called Desiree [Heslop] who had the stage name of Princess. We’d written Say I’m Your Number One, which had an R&B style based on Jam & Lewis. Then because of Dead Or Alive, Bananarama approached us. So things fed on one from the other. The first thing we did with Bananas was Venus, which wasn’t our song, but as soon as we’d done that we went in to write a whole load of songs with them, which became their first series of hits. At the same time, we were getting people turning up from Warner Bros, like Brilliant who were signed to WEA. Suddenly we were starting to have hits and businesses were approaching us, so Pete Waterman’s role was becoming less integral.

How did you start working with Mel & Kim?

“Mel & Kim came to us via Nick East at Proto Records who’d put out the Divine and Hazell records for us. Mel and Kim were just two ordinary kids who’d never been in a studio and, in common with a lot of times, we were asked to do a cover and I thought, ‘No, I want to write songs for them,’ and that’s how we came up with Showing Out and Respectable. We would’ve had a great collaboration with them over a number of years if it hadn’t been for Mel’s ill health and the tragedy of her death.

What about Rick Astley?

“He was the tea boy for us and got the sandwiches! Pete had seen him and thought he had a good voice, so we were going to do a cover of a Motown song, which we did do with him. But I was always saying to Pete, ‘No, we’re writers and this guy’s too good; we’ve got write him something.’ So we sat down and came up with Never Gonna Give You Up and the other stuff, based on the knowledge of his voice. He told us about his long-term girlfriend he’d met when he was five years old, at primary school, and it was a story of fidelity from childhood through to adolescence. So the lyric on Never Gonna Give You Up is about how we love each other, we haven’t actually been physical because we’re just kids, but are we going to take this to the next level or are we going to be lifetime buddies?”

Do you prefer to write with the singer’s own experience in mind, rather than your own?

“That’s the one thing I’ve always done: I would much rather know the artist. Nearly every song I’ve ever written is biographical. Some people sit in their room writing songs, demo them up and send them out to someone who might place them. I would prefer to find an artist and write based on what I knew about them, so I feed off who they are, what they are and, potentially, their capabilities. I factor all that into my thinking, so when I’m sitting down with a blank sheet of paper, it’s not completely ‘blank’ – there are ideas.”

Are you thinking about the melody and topline first, or do you start what the lyrics, or do they come together?

“Well, you sit there tinkering on the guitar or the piano, coming up with ideas and melody riffs, and certain chord structures tug at the heart-strings. It’s alright coming up with a bunch of words and a tune that works, but does it stir your emotions and get you on another level? For me, certain sequences do that. You feel it at deep down level. There is a complicated other scenario where you’ve got structures, words and chords, and you try to fit a tune that works with them, seamlessly, and there’s a skill in that, but is there any heart? That’s the difference, probably, between a good song and a hit song.”

Bucks Fizz with Mike Stock: “If you want to make it in the wider world, you’ve got to make something people want to buy!”

Do you try not to think about those structures or are you a student of these ‘rules’ and know how they work?

“As a kid, I learned that there are rules and as you get to understand them, you can break them. It’s like a woven tapestry: if you pull the rules apart too far, suddenly the material has disintegrated. You can bend the rules, but can’t rip them apart otherwise it won’t work. So knowing how the weaving works is important. For example, on a pop song you can’t waste time on the intro, you’ve got to get to your point. What is your point? It’s normally your title, which is your bullseye, and the verse or the bridge is how you take the listener there, so it’s important. Normally, the chorus is the bit you all want to sing along too, it normally contains the title and, normally, it’s higher in pitch than the verses. So you start low, build up to the high point in tone, and it’s climactic – you give it that lift.”

“Once I’ve got the structure, I sit back and go, ‘Does a casual listener follow this? Is it too complicated? Does it go from A to B in a comfortable way that takes the listener with it? And whilst I’m sure they’re comfortable, occasionally I might want to make them uncomfortable – that’s some of the rule-breaking that I’ll slip to make the song unique.”

Can you give us an example of where you’ve used that technique?

“Well, I sometimes deliberately stuck an awkward key change in, to shock. Another thing I’ve done is extended the line or the cadence, so it ends a bit different. I mean, every song’s got its story in that regard – nearly every hit – but if I said them to you now, you probably wouldn’t think it was unusual, because you got used to it.”

It’s interesting to hear that there’s so much skill and craft that has gone into what some would regard as ‘throwaway pop’.

“That’s one of the biggest problems there are nowadays, because when I say, ‘There are these rules,’ I can hear all the arty ones screaming, ‘There are no rules to music!’ But they’re wrong, it’s how you break the rules in an unusual and unique way that signifies your song out of all the rest. The very first thing you have to learn is how to make your piece of music understandable to the listener. Does it have progression that pulls you along?”

What did you do when SAW split up? Did you ever take a break from making music?

“No, I’ve never stopped. Immediately after that I formed my own record label and collaborated with Simon Cowell on Robson & Jerome, so I did all the production with them. Nicki French we signed and had a hit all over the world with Total Eclipse Of The Heart. At the time, I wasn’t keen to push too many of my original songs because I didn’t have the structure around me – I don’t like throwing my babies to the wolves! And, in the 90s, the industry was going through some massive changes, but I did a band called Scooch for EMI and we had a few hits with them. For my sins, I did the Fast Food Rockers and we had a very, very big hit with them. That’s what I mean, the Fast Food Song is beneath the dignity of most writers, but I knew it was commercial and you have to have that head on occasionally when you’re writing. If you just want to stay in your bedroom, fine, but if you want to make it in the wider world, you’ve got to make something people want to buy!”

What have you been involved with more recently?

“About three years ago, I decided I’d try and do a pop act and took on Shayne Ward who’d won The X Factor. I wrote a bunch of songs for him, got the album in the charts and did pretty well, but then he got offered the gig on Coronation Street and buggered off! Then, a year later, I was on Twitter and somebody says, ‘Why don’t you work with Bucks Fizz?’ I thought that sounded like a good idea, so somebody put us together and we’ve written their album and it’s doing pretty well.”

It’s great to hear you’re still so driven to keep songwriting.

“Well, there’s always another song to write and I’m hoping that one day I’ll write the perfect one! I have to sit down at a piano every day just to keep my fingers going, but also because I’ve got to get some ideas. Whether I’ll need them tomorrow or next week, I don’t know, but that’s what I’m doing every single day.”

Interview: Aaron Slater

The Mike Stock-produced and co-written The Fizz album The F-Z Of Pop is out now. For more on the man himself, go to mikestockmusic.com

![Interview: Jessie Jo Dillon [2025]](https://www.songwritingmagazine.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/jessie-jo-dillon-2-by-libby-danforth-335x256.jpg)

Related Articles