Harry Freedman, the author of a brilliant new book on the singer-songwriter and icon, provides us with his essential picks

One of the most intriguing aspects of Leonard Cohen’s songs is how much he used Bible stories and religious folklore in his lyrics. He was a deeply spiritual man, he spent many years in a Buddhist monastery in California with his teacher Joshu Sasaki Roshi, who was perhaps the most important influence on his adult life. But the religious legends in his music mainly came from Judaism, the religion into which he was born, and from Christianity, which he said was all around him as he grew up in Montreal.

My new book Leonard Cohen: The Mystical Roots Of Genius explores the folklore, legends and Bible stories that he uses in his work. I have not attempted to guess what was going on in his mind when he wrote a particular song. Instead, I have tried to discover what his sources were, what their original context was, what the stories and ideas that lay behind them were and how Cohen harnessed them for his own purposes. Approaching Leonard Cohen in this way gives us a new way of listening to him, and helps to make his always profound music even deeper.

More ‘Songs In The Key Of’ posts

Harry Freedman’s book Leonard Cohen: The Mystical Roots Of Genius

Hallelujah is a deeply, religious song. Using legends from the Bible and the Talmud, Cohen sings about King David. Of how his kingdom began to fall apart after he committed adultery with Bathsheba and sent her husband into battle to die.

King David is said to have written the Book of Psalms, where the word ‘Hallelujah’ comes from, and in the mystical, kabbalistic tradition words are sacred. Each word, Cohen says, has a blaze of light in it. And yet words are also profane, we use them to swear and abuse. We rely on the power inherent in words, especially when everything goes wrong. When there is nothing else left for us to do, the best we can aspire to is to sing Hallelujah.

ANTHEM

Leonard Cohen described Anthem as maybe the best song he had ever written. It took him 10 years to write it. The name hints at the song’s religious character. In early English, the word ‘anthem’ was used to describe a sacred musical composition.

We hear echoes in the song of the biblical book of Ecclesiastes, which was almost certainly one of his sources for his composition. He described the song as a reflection on the flaws of humanity and on our imperfections, which is also one of the themes of Ecclesiastes. But like the biblical book, Anthem is not completely negative. In Ecclesiastes we hear that there is a time for everything – Pete Seeger used it for his song Turn! Turn! Turn! which was a hit for The Byrds in 1965. And in Anthem, we hear a kabbalistic legend about a cosmic catastrophe when the earth was created that allowed evil to dominate. But the legend tells us that even when everything is broken, all is not completely dark. Or as Cohen puts it: there is a crack in everything, that is how the light gets in.

WHO BY FIRE

Several of Leonard Cohen’s songs can be thought of as prayers. Who By Fire is one. It is Cohen’s version of a prayer that is recited in the synagogue at New Year, that anticipates what may happen to us in the year ahead. The synagogue prayer was written in the eleventh century but was based on a much older composition, dating back to the third or fourth century, which the ancient mystics used to chant as they tried to achieve mystical union with the divine.

Leonard Cohen has brought the prayer up to date. He said that the melody was derived from the tune he heard in the synagogue as a boy. Cohen’s catalogue of possible fates awaiting us is both dark and playful. He has people dying from barbiturates, by their own hand and in solitude; others die from love, by their lover’s command, or in the merry month of May. And he ends the song with a question. Whose voice, he asks, is calling us? As in so much of Leonard Cohen’s music and poetry, he brings us back to the great existential question. What is out there? What is the nature of that which is beyond?

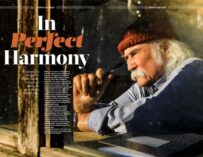

Leonard Cohen. Harry Freedman observes: “Babylon features a lot in Cohen’s music, he uses it as a symbol of darkness, corruption and evil”

THE WINDOW

Windows crop up a lot in Leonard Cohen’s music. They symbolise boundaries between two locations, or dimensions, or states of being. As we know, light passes through windows, but so also, under the right conditions, can souls, dreams, desires, hopes and prayers.

In his song The Window, Cohen is singing to a soul. He asks it why it is standing at a window susceptible to bodily pride and beauty, suffering from the challenges of the age. Why, he asks, doesn’t it pass through to the other side, to a place of holiness and light? He is not speaking of death, the experience he is encouraging the soul to take is a mystical, purifying experience, the unio mystica which in many faiths is the ultimate religious experience. Cohen describes this experience poetically, using imagery drawn from the kabbalah.

STORY OF ISAAC

This is Cohen’s contemporary retelling of the biblical story of the near-sacrifice of Isaac. It was, he said, a song about those who would sacrifice one generation on behalf of another. What is interesting about this song is the way in which he fuses Jewish and Christian ideas and images – it is something he does a lot but it is particularly noticeable here. He starts by retelling the story from the Hebrew Bible but then shifts to the crucifixion, symbolised by a broken bottle of communion wine. Story of Isaac is a great example of how Cohen uses a Bible narrative as a metaphor for the world we live in.

BY THE RIVERS DARK

This is a song based on Psalm 137, about a group of Jewish refugees 2,500 years ago who hate being in Babylon and are unable to forget their homeland. The psalm was adapted in the 1970s by the Melodians and by Boney M. as Rivers Of Babylon. Cohen’s adaptation is different, he turns the psalm around to sing about a refugee who is trying to come to terms with his new home. Babylon features a lot in Cohen’s music, he uses it as a symbol of darkness, corruption and evil. Cohen’s refugee knows he must make a new life for himself in this negative. He succeeds, but he is damaged in the process.

SUZANNE

This is an autobiographical song. The Suzanne he sings about, Suzanne Verdal, was something of a muse for him, they spent a lot of time together. But they never became lovers. He said that “I touched her perfect body with my mind, because there was no other opportunity.” When he visited her she would give him cups of Chinese tea with bits of oranges in it. They would go for walks together and pass the sailors’ church overlooking the harbour. The church has a wooden tower, just as in the song. On it is a statue of the Virgin Mary, known locally as Our Lady of the Harbour. She figures in the song too. Apparently, if you climb the stairway up to the top of the wooden tower you will see the lyrics of Suzanne written on the walls.

DIFFERENT SIDES

Different Sides is a song about imaginary paradoxes, about two groups of people, who find themselves on opposite sides of a line that doesn’t really exist. Each side considers itself different from the other, but really they are both the same. He makes his point in the song by posing three riddles, the answer to each one is a paradox. The people he is singing about are followers of Judaism and Christianity, who see themselves as different. But, he says, although they look different to us, in heaven’s eyes they are the same. The song explains why Cohen is so comfortable incorporating images from different belief systems into his songs, with no sense of division between them.

Harry Freedman: “Several of Leonard Cohen’s songs can be thought of as prayers”

DON’T GO HOME WITH YOUR HARD-ON

Leonard Cohen was not a typical rock star. He was always well dressed and polite, nobody ever accused him of being rude or crude. That’s why Don’t Go Home With Your Hard-On is such an anomaly. The song appears on the Death Of A Ladies Man album which was recorded in Phil Spector’s chaotic and dangerous studio, a recording experience he found very traumatic, that resulted in an album panned by the critics. While they were recording Don’t Go Home With Your Hard-On, Bob Dylan burst in, accompanied by two women and a bottle of whisky. Then Allen Ginsberg and his lover arrived. They can be heard in the background of the track, an impromptu, boozy, discordant backing group.

IF IT BE YOUR WILL

The formula If It Be Your Will is how many Jewish prayers begin. Leonard Cohen told the audience in London’s O2 centre that the song was ‘a sort of a prayer’ written ‘a while ago’ when he was facing some obstacles. In this very personal composition, Cohen asks the deity if he is supposed to be silent, to stop singing. If so, Cohen says, he will comply. But as the song proceeds Cohen’s prayer stops being personal, it is almost as if he senses that his prayer is gaining him divine favour and his words are being accepted. Instead of focusing on his own issues, he ends by praying for healing for the whole of humanity, if it be the divine will to make them all well.

JOAN OF ARC

Leonard Cohen was intrigued by Joan of Arc. He mentions her in three of his poems and this track from his Songs Of Love And Hate album is devoted to her. He said that she fascinated him because, “From the point of view of the woman’s movement she really does stand for something stunningly original and courageous.” Joan of Arc was burnt at the stake in 1431 after leading the French army in battle against the English. In his song, Cohen constructs a story of fire pursuing her as she rides alone at night. The fire declares its love for her, she is immediately seduced and the fire climbs inside her, making her its bride as it consumes her body. Cohen agreed that it was a strange song, he said that when he recorded it he had a strong religious feeling. ‘I don’t think it will happen again,’ he said.

YOU WANT IT DARKER

Leonard Cohen wrote this song when he knew that he was dying. It is his parting message to the God who he never mentioned by name but who was always present in his music. In the background, we can hear the choir and the cantor of the synagogue in Montreal where he grew up. Cohen sings the opening line of the Kaddish, the Jewish prayer recited when someone dies, follows it with a line about the crucifixion and then delivers a short eulogy to the victims of the Holocaust. And then he repeats the Hebrew word that crops up only occasionally in the Bible, but always at moments of great drama: Hineni. It means “here I am”. Leonard Cohen, knowing his death is fast approaching is telling God he is ready. It feels like a very brave thing to do, to submit to death with such composure.

Harry Freedman is Britain’s leading author of popular works of Jewish culture and history. Leonard Cohen: The Mystical Roots Of Genius is published by Bloomsbury Continuum in hardback, audiobook and ebook and is out now. Find out more at bloomsbury.com

More ‘Songs In The Key Of’ posts

Related Articles