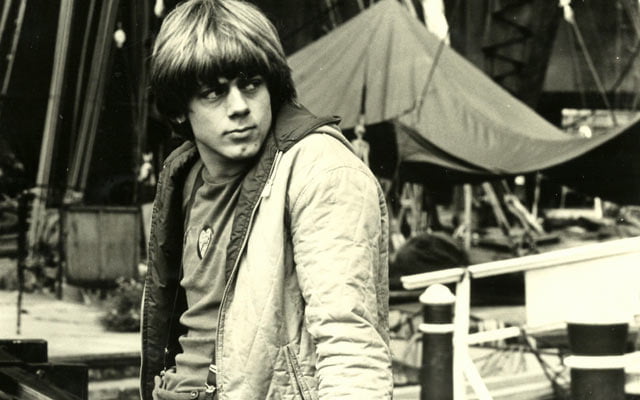

Jilted John: “Part of the reason it is so different is because it was written by a young lad…”

We hear about a punk song whose protagonist was so heartbroken he cried all the way to the chip shop

Jilted John is one of the best examples out there of a parody song which transcends its genre. The work of English comedian Graham Fellows, it might have started out as a satirical take on punk music but now sits proudly alongside anything released by the Sex Pistols, Buzzcocks or Clash. Fellows clearly has a knack of creating such tunes because he subsequently went on to further success with his singer-songwriter character John Shuttleworth, whose songs like Pigeons In Flight also elevate themselves out of their comedy beginnings.

Originally the B-side to the track Going Steady, it was the advocacy and air time provided by legendary BBC DJ John Peel which made Jilted John impossible to ignore, as Graham explains here…

Released: August 1978

Artist: Jilted John

Label: Rabid/EMI

Songwriter(s): Graham Fellows

Producer(s): Martin Zero

UK chart position: 4

US chart position: –

“I had just started studying at the Manchester Polytechnic School of Drama in the autumn of 1977 and would see this battered acoustic guitar in the canteen that various people would pick up and strum during tea breaks. I started playing it and tuned it to a chord after someone had advised me that it was one way of playing very simply, just putting your finger across the frets to make a bar.

“The first thing that came was this samba-esque riff and on the back of that I started writing this lyric which was parody of punk, making fun of some of the songs that I was hearing on the radio. That included the phrase, ‘Ere we go two, three, four,’ which I’d heard on a few records. It evolved from there. Early versions were quite slow and folky and it toughened up during the rehearsal period.

“The first demo was just me playing the acoustic guitar and my friend Bernard Kelly banging out a rhythm on a Monopoly box lid, he went on to play Gordon the Moron on Top Of The Pops because he was very tall and gangly.

“I played it to a few people who said it was catchy and I should do something with it, so I found a local recording studio in Sale, Manchester and we went and recorded it there. I paid the princely sum of £25 for a little demo tape and I got a few musicians to do it for next to nothing. I then walked into a record shop in Didsbury and asked if they knew any punk record labels. They mentioned Stiff Records in London and one that was just down the road called Rabid Records. I went down the road and found the record company with all these punky guys sitting around drinking coffee, which wasn’t very punk. I had the tape on reel-to-reel and they had a tape machine so they stuck it on there and then and said, ‘Can we hang on to this?’ It was my only copy so I took it home, but they liked it and wanted to make the record, so rehearsals began.

“In those days recording time was very expensive so it was all about rehearsing first. We had weeks of getting together in a cellar in Withington. John Scott played guitar and bass and Tony Roberts was the drummer. Bernard sang backing vocals, he was cooler than me and knew more about music and the punk scene and he was a very good person to have around.

“We recorded it at Pennine Sound Studios in Oldham in March 1978 and I absolutely loved it. It was very exciting as it was my first time in a proper studio and we did it all in one eight-hour session. Martin Hannett hadn’t really heard the song that much so he came into it quite fresh, which was good. He suddenly got the idea to do the catchy bass riff on the breaks and it was also his idea to fade in the, ‘Yeah yeah, it’s not fair,’ bit. He really did put some fairy dust on the thing and he went back a couple of days later to remix it.

“It was doing well in the indie chart and Rabid couldn’t meet with the demand so several companies were invited to take it over and EMI International were the highest bidder. John Peel must take big credit for the success. He played it a good few times and his show was extremely trendy and influential so then other Radio 1 DJs who wanted to bask in his coolness started playing it, even people like Simon Bates. It was a time when novelty singles were quite acceptable.

“Part of the reason it is so different is because it was written by a young lad who hadn’t really written any songs before. So it has a rawness and an innocence. I’ve written hundreds of songs since and would never consciously write a song with that structure now because it breaks all the rules. The melody should be repeated every verse but for some reason I minimised the tune. It becomes more chant-like and the tune almost disappears as John gets more plaintive and sad, but I wasn’t really thinking of those things. The riff carries on for the second half of the song and it doesn’t waiver from that. I wrote it when I was 18 and didn’t know that you had to put in a chorus more than once.

Graham Fellows: “There wasn’t a real Gordon but it was one of those trendy names, like Gary or Colin”

“There was a big inspiration and that was John Otway. He had this hit called Really Free in 1977 and I just loved that kind of spoken delivery and the way he half sings during the chorus. There was an everyday quality to the lyrics, it was just throwaway and had a quirkiness that I wanted to copy. I’d always thought there were so many love songs that spoke in generalities, ’If you leave me it will break my heart,’ ‘I can’t go on without you,’ all that shit that I never believed. I like songs with detail. I was also aware of Squeeze and the lyrics of Chris Difford who shares a love of the minutia and detail and rhyme.

“There wasn’t a real Gordon but it was one of those trendy names, like Gary or Colin. They were working class names but were guys with cool hairdos and leather jackets and the shirts with the big collars. And ‘Gordon’ happens to almost rhyme with ‘Moron.’ But my childhood sweetheart was a girl called Julie, so that’s that.”

“I’m in the middle of writing a song about what John’s up to now. I suspect he’s still a bit of a loser who goes to the library a lot and carries a plastic bag, he might still live with his mum or on his own. But it’s not known for certain, you’ll have to find out.“

Related Articles