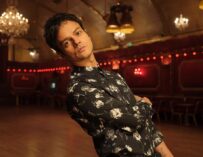

The multi-award-winning songwriter, jazz musician and broadcaster reveals why he was “full of doubts” during the making of his album

With 10 million album sales to date and his successful weekly jazz show on BBC Radio 2, Jamie Cullum is a celebrated musician with a career spanning more than 20 years. His legendary live shows have seen him perform and work alongside artists as diverse as Herbie Hancock, Pharrell Williams, Kendrick Lamar and Lang Lang, whilst his major label breakthrough, Twentysomething sold millions of copies, and made him the fastest-selling British jazz artist in history.

That album and its follow-up Catching Tales saw him nominated for a BRIT, a Grammy and numerous other awards around the world. He was even nominated for a Golden Globe Award for Best Original Song in 2009 for Gran Torino, which he co-wrote for the Clint Eastwood movie of the same name.

Jamie called us from Stuttgart, Germany before soundchecking for a festival, and told us all about the writing of his eighth studio album, Taller. It turns out the story behind the new record actually started 10 years ago…

We understand your new album has been a few years in the making. Tell us about how it all started…

“Well, I can trace it back even earlier, to a song I wrote for the Clint Eastwood film Gran Torino. That was a turning point for me, in a sense that prior to that I always felt like songs were something I wanted to do. I thought of myself as someone who writes song, but I would be slightly reticent to define myself as a songwriter. I would’ve said [I did] many different things, and I also write songs. And I think after I did [Gran Torino], I was really pleased with the song and the way it went down, and how it came together. That gave me an awful lot of confidence and it felt like the songwriting gods were tapping on my skull going, ‘Come on, write more songs, be confident about it!’

“And that started with the album I followed up with, called Momentum, where I really jumped into the songwriting. But I think by the time I came round to making Taller, I knew that I wanted to make an album of just my songs. I was like, ‘I’m going to make 10 – or a maximum of 12 – of my original songs.’ I did actually start something about four-and-a-half years ago, but I ended up losing confidence again and dropping the initial songs. I just felt that when I listened back to those early things I wrote for this album, they were just lacking.”

Which song was the one that gave you the sense that you were on the right track?

“It was Drink, which funnily enough is like the baby of these songs, in its own way – the seed where the others grew from. I just felt it had a lyric that summed up what the album would be about, which is finding the nuance between good and evil, not tarnishing everything with the brush of ‘yes’ or ‘no’, but finding that slightly grey area between what people think is true. So there was that kind of stuff embedded in the lyrics, but also an architecture to the structure of the song that I found

really pleasing.”

Talking of your approach, how do you generally tackle the writing process? Do you tend to throw yourself at the piano and let things emerge, or do you prefer to start with the pen and paper and craft a lyric first?

“The first way you described is how I would’ve approached it in the past – sit at the piano, bash around some chords, improvise, wait for some words to come out while I was singing, then gradually build a song. This time, it was totally different because I was starting from lyrics first. I took a lot of inspiration for these songs from my general notepad writing – kind of journals, if you want to call them that – daily witterings and pages with things written down when I was trying to work through certain problems or issues in my life.

“I don’t mean a ‘I went to the shops, I had a glass of white wine…’ kind of diary, I just mean I’ve always found journaling and writing is quite therapeutic, and a way to organise my thoughts, to make sense of things I find really tricky, from quite a young age. Whilst I didn’t go into those diaries and go, ‘I’m going to write songs from this,’ things would emerge from there, which I would go, ‘Oh that would be a really interesting song or poem.’

“Songs like The Age Of Anxiety, Life Is Grey, Taller, You Can’t Hide Away From Love – they were all lyrics before. I was sitting at the piano with quite a fully formed lyric and that was a totally new way of working. I think it’s because on this album I really pride the lyric higher than I ever have done, and that’s not to say I haven’t tried it before, but I thought of myself as a lyric-writer this time – I bestowed that upon myself, without feeling too shy or humble about it. Armed with those words, I went to the piano and tried to keep it as simple as possible, and not swathing myself in production too early on. Some of those songs then kind of took shape with those words, and once I’d written the song more fully, I’d go back and rewrite some of the verses, to give them more depth or react to the music.”

The production is really strong on this album. Did you ever write around a beat or a backing track, or did that come later – working with Troy Miller – when the songs were fully-formed?

“Well, with quite a lot of the songs, I came to the table with a very clear sense of the production. Drink would be a good example of that. I mocked the entire thing up in a pretty crude way, but I had drums, bass, guitar and all the orchestral parts, and I knew how I wanted that song to build and how I wanted it to work. Taller is another example of that. With Life Is Grey, I had a very clear sense of how I wanted it to work and again I knocked up quite a lot of that.”

Were you putting that all together in a studio at home, on your own?

“Yeah, quite a lot of final versions of the tracks were recorded at mine or we ended up using the piano and vocal from my original demo, and maybe a bass part here and there. That’s not to diminish in any way what Troy brought to the situation. He brought total, helpful reinvention on some of the tunes, and real major refinement. He was even able to refine piano parts to help the song ‘speak’ better. His incredible orchestral arrangements were based around ideas I had, but he’s someone who actually knows how to put that stuff together. So it was a great meeting for us, because we could work in my studio and his studio and provide nearly everything that we needed – there were very few things we couldn’t do with a combination of what we both bring to the table. By the time I’d written the songs – because I love being in the studio so much – certain songs had a clear imprint of what I wanted to do, and some songs I took to Troy and went, ‘Here’s the demo vocal. I want the song to speak like this but I don’t know how to do it.’ Then he would lay down some drums, I’d get on the bass, we’d fiddle around on synths and different patches, and play – not hold ourselves back.”

That intimacy and vulnerability contrasts nicely with much of the rest of the album, where it’s clear you’re having a lot of fun. The playful lyric of Mankind comes to mind. Did you start that song with the concept, or did that emerge as you wrote it?

“That one has a very specific genesis. I had the opportunity to book a gospel choir for a commercial project that ended up being for an advert, and I realised I had the choir for an extra hour and a half. The night before the session, I wrote the chorus to Mankind and had the idea of not wanting to give up on mankind. I managed to get the structure of the song quite quickly and recorded the gospel choir. With recording, I programmed a beat on my MPC at home, and I borrowed an amazing synthesizer called a CS80 – a massive Yamaha synth that was used on the Bladerunner soundtrack – and I recorded the simple chords. Then I had a poem I’d written in my notebook about what I felt I’d lost by not being religious any more – I grew up Roman Catholic and I gave all that up. I think that’s what the verses are about: what it must be like to be a radical believer and what it’s like to see God when you’re on drugs, and that kind of thing.”

After that bold and ambitious track, you have Usher, which is again a lot of fun but more lighthearted. You wrote that with your brother Ben, didn’t you?

“That was me and my brother in his studio having a good time. Me on the keys, he would be on the drums or the bass, and we’d set up a loop and just jam – probably a lot of whisky was consumed! We would’ve had that verse and the melody, then the lyric was added afterwards, so that was in opposition to what I said at the top of this interview. I knew we had a really great funk song but I wanted a lyric that was subtly much deeper than it first appeared.

“I’ve actually never met Usher. I was reminded of something my wife said when our babies were very little and I was away on tour: it was early in the morning, the kids were crawling around the room and the popstar Usher came on the television. She used to live in New York in the early 2000s and led quite a glamorous life, and she went, ‘Oh my God, I used to know Usher,’ and was reflecting on how different her life felt at that precise moment, surrounded by babies and it being five o’clock in the morning, having had no sleep and life feeling unglamorous…it was a kind of psychedelic dream. So I thought, ‘I used to know Usher’ could be a great hook and have it like a psychedelic funk thing a bit like Prince might do.”

On For The Love you say, “Every time I touch the piano I’m just full of doubts.” Is that honestly how you feel?

“Absolutely. It’s just honesty with what it’s like to be in the process of songwriting. Some days you feel like you’re Paul McCartney and sometimes you don’t. Yes, it does hark back to those days, but it also how I felt a few days ago when I was trying to write a song. Also, it’s how your instrument treats you poorly sometimes – it’s your teacher, your leveller, your humbler and your dose of realism – but you keep coming back to it. It’s like a love affair, like a relationship, but relationships can be hard. There are doubts and hardship in everything, but you come back for the love of it and to be able to keep coming back is the trick.”

You mentioned how the instrument can treat you poorly. Is that because you’ve been playing the piano for years, perhaps you know it too well?

“I don’t know the instrument too well, I could know it a hell of a lot better! There are so many great ways to limit yourself and re-enact that feeling. Like last week I tried to write a song on the MPC with just a couple of samples. I think Jack White’s really good at doing that and great to take inspiration from. To just go and buy a mandolin and try to write a song on that, or borrow my friend’s harp, or buy a new synth patch. You can also limit yourself on the instrument you’re saying, ‘I’m just going to use a couple of chords’ or ‘I’m going to write a song that doesn’t rhyme’ or ‘I’m going to write a song based on a newspaper article I just read.’

“I think there are so many different ways to be creative – I derive quite a lot of inspiration from reading books about writing that are not about songwriting, like short story writing – go and watch a great movie or a movie you’ve never heard of, in a different language; go to an art exhibition; go to a death metal gig that you’ve never been to before; take inspiration from places that are unexpected – it’s out there, it’s all ready to be caught in your net.”

That’s great advice. You’ve worked with some top songwriters and producers over the years – Dan The Automator, Guy Chambers, and Jamie Hartman on the latest album. Do you actively select your collaborators?

“I’m not a ‘grand master plan’ kind of guy. One of my most surprising collaborations was with Pharrell and that was something that happened by accident. He’d heard a track of mine and loved it and said, ‘Come to Miami next week,’ and I’m like, ‘Er… okay!’ With Guy Chambers, I obviously know so many of his songs, I met him and went, ‘Oh would you ever like to write together?’ And he was like, ‘Yeah, great.’ So I don’t write down a hit list of people I want to work with, but if I hear someone’s record and it turns out they’ve worked with this person or that person, and I think it’s great, I’ll definitely try to reach out to them. But generally, it’s people I meet by chance. If a songwriter has experience and has written some songs you think are good, it’s always worth a day or two – not necessarily just to get a song out of it, but to increase your ability to write and it’s always good to mix it up. There’s very little lost in trying something out, I always think.”

Tell us about your most frequent collaborator over the years: your brother, Ben. Was Pointless Nostalgic the first song you wrote together?

“Actually, I hadn’t really written anything before Pointless Nostalgic – definitely nothing I would’ve played to anyone! That song was something Ben wrote entirely on its own, I didn’t have any contribution to that at all. Our first collaboration song would’ve been Mindtrick on our album Catching Tales. Prior to that, I hadn’t really done any co-writing. Songs like All At Sea and Next To You Baby felt like accidents – I hadn’t really realised I’d written a song!”

Looking at your discography, you can see how each album has gradually involved more of your own songs. Where do you go from here?

“Again, I go back to what I said earlier: I don’t have a master plan. I’m continuing to write at the moment because I enjoy it and it’s a creative outlet, but if a cover idea came to me and I felt like it needed to be on an album, I wouldn’t shy away from it at all. It’s the same with collaborations: I think I’m just going to continue writing and writing. If you were to pin me down about what my next album would be, I’d say it would definitely be more of my songs, but I might think less about writing 10 or 12 songs – I might just write songs and put it out, write another song and put it out, for a while. I’m not sure yet.”

Interview: Aaron Slater

Related Articles