They Might Be Giants’ John Linnell on Birdhouse In Your Soul: “It’s just a celebratory song with a poppy melody and the lyrics could almost be anything.”

John Linnell recalls the story behind their catchy-as-hell alt-rock classic whose words were written years after the melody first appeared

High school friends from Lincoln, Massachusetts who reunited in Brooklyn in 1981 and formed a band, John Flansburgh and John Linnell have been making music as They Might Be Giants for the best part of four decades now. Balancing keen melodic sensibilities with razor-sharp wit and an eye for interesting detail, they’ve remained consistently strong songwriters from their self-titled debut album right up to recent single I Can’t Remember The Dream. They also have a particular knack for writing songs that can be enjoyed by younger listeners (check out their quartet of children’s albums and the song I’m Not A Loser which they contributed to Sponge Bob Squarepants The Musical).

The height of They Might Be Giants’ commercial success came in 1990 with the release of the album Flood. Selling over a million copies it was given a massive push by lead single Birdhouse In Your Soul which hit the Top 10 of both the UK Singles Chart and US Modern Rock Tracks chart. Still very much a radio favourite, John Linnell does his best here to remember as much as he can about a track which, not to put too fine a point on it, is up there with the juiciest of earworms.

First published in Songwriting Magazine Autumn 2021 issue

Released: 1989

Artist: They Might Be Giants

Label: Capitol Nashville

Songwriters: John Flansburgh, John Linnell

Producers: Clive Langer, Alan Winstanley

UK Chart Position: 6

US Chart Position: –

“It started long ago. I was living in Hell’s Kitchen in the early 80s and I’m pretty sure that’s when I started coming up with the harmonic melodic bits, because I was doing a lot of that at that time. Then, you know, five years later, we were making our third album and I’d kind of come up with the lyric. By that time, in 1989, John and I were both in Williamsburg, which had not yet become overrun by hipsters, it was still just like a Polish/Italian neighbourhood. I was sharing an apartment with my dear friend Brian Dewan and I think most of my songs from Flood were written in that little apartment on Havemeyer Street. An old chapel for a funeral home, that’s where we lived.

“I’d moved from Manhattan to Brooklyn, and kind of was in a more comfortable situation. By that time, you know, this was a happy time in my life. In the late 80s, when I moved to Brooklyn and felt like there was a community of like-minded people and we were playing in these little clubs in the East Village and it was a really fun time.

“My memory is that I came up with a melody and a set of chord changes and then I didn’t really have a lyrical idea. It revolved around this pretty simple thing where it modulates up a minor third, that’s the chorus of the song. The middle has this sort of surprise modulation from C to E flat, then it kind of collapses back down to C again. And it’s short, it’s only eight bars, I think. So it cycled through that kind of thing and it reminds me of something, some Dusty Springfield song or something that maybe did the same thing. And yet, because I can’t quite remember, I don’t know exactly what I was ripping off. That’s actually okay, it’s possible that it’s distant enough from whatever inspired it that it counts as an original idea.

“I came up with lyrics that just fit this completely pre-set melody. This is a little bit of an explanation of why the lyrics themselves are so elliptical, you know, there’s a concept of ‘Who’s the narrator?’ It’s a nightlight. And then, ‘What does the nightlight sing about?’ you know. It all sort of follows from this slightly weird concept, which in a way is almost not the point. It’s just a celebratory song with a poppy melody and the lyrics could almost be anything. I feel that way about a lot of songs I like. So that’s kind of the vibe, it’s a freeform lyric that has this very fanciful premise. It’s kind of a love song but what is being expressed, I don’t exactly know.

“That’s maybe part of the method that John and I like to engage in, this sort of unfiltered way of expressing an idea where you’re trying not to be too much of a gatekeeper, when you’re writing lyrics. You try not to worry too much about what it means and just let the poetry of it flow. You can have bad ideas that way but you also have the opportunity to edit and make little changes if there are some things that you like. Even if the ideas are not completely clear but they’re appealing for some reason, you can focus on those things.

“I found the old MIDI file for the original recording and the only thing I learned from that was that there were sections of the song that got added later, that didn’t exist in the original version. They were these musical interludes. So, the original MIDI file has the beginning, sort of intro set of chords, the, ‘I’m your only friend’ section and then it cuts directly to the chorus. Obviously, at some point, I thought, ‘I want to make more drama,’ so I added this little organ thing that’s doing octaves. That was probably six months later because the file that I have is from February of 1989 and then the final MIDI file is from that summer, July. So six months of existing in this one form and then I added the sections probably with the encouragement of our producers.

They Might Be Giants’ John Linnell on Birdhouse In Your Soul: “We decided to add this Summer In The City thing as an instrumental break.”

“The instrumental break had to do with Clive and Alan saying, ‘The song has to be longer and maybe could have a part where you stop singing.’ That’s why there’s this Summer In The City section, which we directly and consciously were borrowing from the Lovin Spoonful song. It was a reflection of the fact that it was probably 100 degrees in New York that summer we were recording. We were mostly in the studio but we’d go out and take little walks and it was boiling hot. I’m sure this put us in the mind of that song which was a huge hit in 1966, apparently one of the hottest summers on record in New York, which I actually went back and researched. Then I was curious, I was like, ‘Well what about 1989?’ It turns out it didn’t even rank, it was really hot to us but not one of the record-breaking heatwaves here in New York. But anyway, we decided to add this Summer In The City thing as an instrumental break. Then we added these trumpet blasts.”

“All of this was assembled in the studio after the song had been written. As I said, the little octave-y organ thing must have shown up later that year after I’d originally written the song, because that was not in the original debut. I almost ruined the song, because I wanted it to sound more normal. When we started working with Clive Langer and Alan Winstanley, I played them a new demo that I’d made where I’d completely changed the rhythm section to make it more like a standard pop song. In the finished version, the version that was released, there’s a crazy drumbeat where the snare is hitting on every beat, and then the kick is coming in on the off beats, which is completely wrong and crazy, but that was the original version. I played that to these guys and they said, ‘Okay that’s what we’re gonna use that as a spotlight track.’ Then I made this new demo and I completely changed the drumbeat and they were like, ‘You ruined it. Why did you do that?’ So we went back to the original drumbeat.

“John has much more of a producer’s ear and so he was always much more concerned with the sonics. I think he and Clive Langer did a mind meld on a lot of this stuff. Specifically, John was very concerned about not trying to hide the lyrics. There’s a certain style of rock music where the lyrics are obscured which he referred to as “the kitty litter approach”. You scrape some production over the thing that you’re embarrassed about, like you’re covering the shit with it. He felt that if you own the lyrics they should be fully audible and they should be clear. You shouldn’t bury them too much, everybody should be able to hear the lyrics. That was very much a Flansburghian philosophy that I adopted, which I never considered until he started talking about it. He was very into standing by what you were doing and owning it and not being ambivalent.

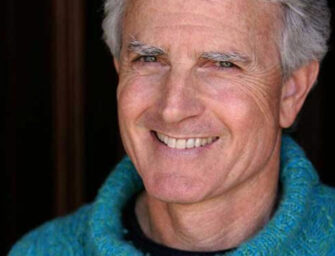

They Might Be Giants’ John Linnell on Birdhouse In Your Soul: “I think it’s a good song and we still like playing it, but I don’t know what it is specifically about it.” Photo: Shervin Lainez

“We picked it as one of the singles, because Clive and Alan heard all the demos for Flood and said, ‘Birdhouse… is going to be one of the ones we will work on with you.’ We only had enough money to pay them for four songs, I think, and the rest of it we produced ourselves. They were definitely excited about that one and then I obviously was kind of nervous and got cold feet and tried to make it sound more normal and luckily they were there to save me from myself.

“I think it’s a good song and we still like playing it, but I don’t know what it is specifically about it. There was a combination of happy things going on then where we had made two very successful indie albums and then, on the strength of that, we got signed to Elektra. They are obviously a powerhouse. So, in that regard, we were fortunate that, by the time of our third album, we were writing confidently and felt like we’d established ourselves. In our own minds we knew what we were doing and we were confident enough to hire somebody we’d never met before to come and produce us and we had this big corporation that was going to give us international distribution on a level that we’d never seen before. So, there are a lot of elements that came together, obviously, but I can’t really speak to what in particular about the song connected.

“It was a much bigger hit in the UK than it was in the US. We’d been to the UK before but we showed up in 1990 and were suddenly recognised by strangers. That was a really unusual experience. John and I drove up to the Lake District that year, just for a little break after we’d done a show in Manchester, and we were in some tiny little pub and people in the bar recognised us. We were in this rural part of part of Britain, so that was really a thrilling, weird, new experience.

“One thing, and I’m sure other bands say this about playing the hit in the middle of their show, is that you may feel like you’re struggling to make it fresh and exciting for yourself, but when you’re in front of an audience, and they’re reacting… This is the song some of them have actually been waiting to hear, not the ones in the front row, but the ones at the back. They don’t know everything else you’re playing and this song in particular is exciting for them, that has an infectious energy to it. We like it when everybody’s getting excited in the crowd and so that that goes a long way.”

Related Articles