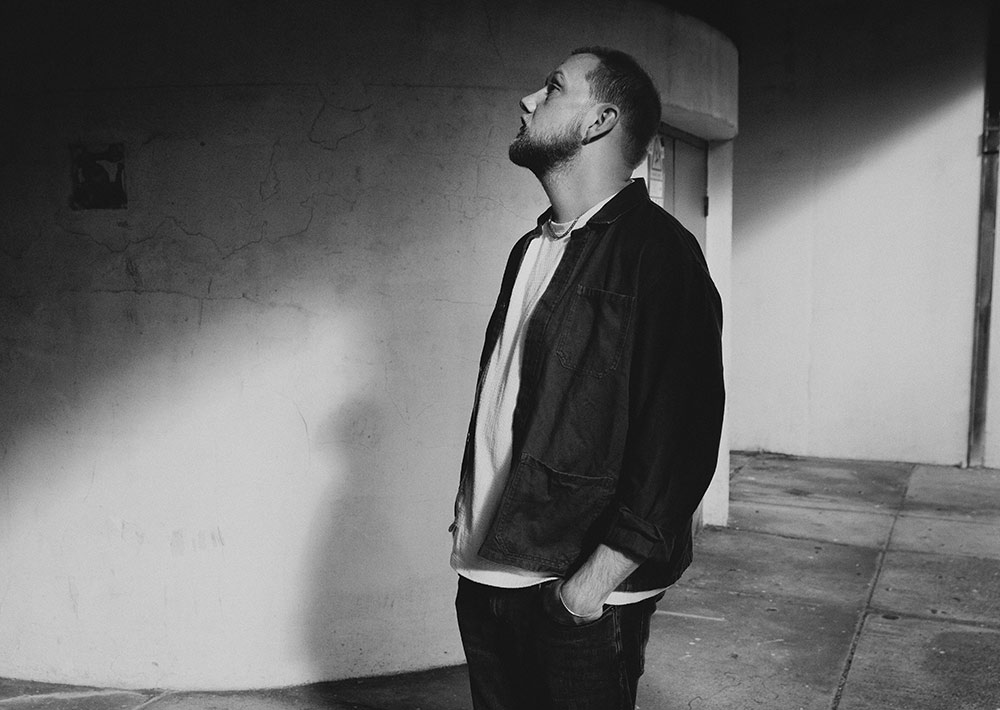

Alexander Wolfe: “Including the voicemail felt uncomfortable, but I like uncomfortable.”

Step inside a filmlike album that acts as an intimate, unflinching exploration of family, mental health, love, and masculine expectations

Alexander Wolfe, raised in Woolwich in the 1990s, has long used music to navigate the challenges of his upbringing and the pressures facing young men in contemporary Britain. Known for his layered, atmospheric compositions and semi-autobiographical lyrics, Wolfe combines piano-driven arrangements with an emotive vocal clarity to explore mental health, grief, relationships and masculinity.

Everythinglessness, his latest album, was written following a period of intensive mental health treatment in 2023, during which Wolfe transformed his struggles with depression, anxiety and ADHD into a record of reflection and resilience. The album continues his focus on vulnerability as a form of strength, addressing experiences often left unspoken. In the following feature, we’re taken deep inside the creation of the album…

I see the album as a film

PRELUDE

I see the album as a film, and this track functions as the opening scene. It’s where we find the boy – now a man – searching through old tapes, sifting through memories, trying to find some kind of guidance. He hears his ex-girlfriend’s voice and fast-forwards past it. There’s an old self-help tape on masculinity that comes on briefly before he turns it off. None of it feels useful. He realises the story has to be told from the beginning.

When I was writing this album, my mental state was fragile. I found music with lyrics difficult to listen to; it felt too direct, almost invasive. I was listening to a lot of Japanese ambient music, particularly Hiroshi Yoshimura and Sasumu Yokohama. I think it gave me the space I needed without instruction. Those ambient textures influenced the pacing and production of the track, and the album, actually.

LEWISHAM CONVERSATION

This song looks back at his parents’ meeting, and it establishes them as people shaped by their conditions. The mother is in the middle of an existential crisis: she feels too much, too fluid, constantly questioning. The father has been hardened by inherited ideas of masculinity; he can’t bend, he’s overly certain, and that certainty makes him brittle.

The song starts with their first conversation in a bar, which sits somewhere between a meet-cute and an argument about human existence. In the third verse, it jumps twenty years forward. They’re living together, they have a 15-year-old son, and the song ends with the boy skipping school and launching into an existential rant of his own. That moment was important to me. It establishes him as very much his mother’s son, emotionally and philosophically.

He says, “Mama, when the president talks, I can see the greed in his veins. I think he’d drown his own children to keep hold of the reins, now all I can see are those headlines… Those headlines, and we’re all just drinking the milk and eating the lambs, no one’s looking down at the blood on our hands. If you’re sick, then you die, if you’re black, then you’re blue, and you’re fucked if you don’t and you’re fucked if you do.”

I originally wrote this as a kind of alt-country song. It was closer to something like It’s Alright, Ma (I’m Only Bleeding) by Dylan. When my co-producer Brad [Spence] got the track, he stripped everything back, took out the guitars and drums, kept the vocal and the piano, added the beat, and we rebuilt the track around that core. It took me a while to get used to it, but it helped the song feel human, less like a retrospective and more like it’s living. It has this feeling of unresolved tension, I think. I remember a phone call where I wasn’t sure about it, and he said, “It used to feel like a song, now it feels like a life,” and I think that’s true.

From there, the rest of the album follows the boy between the ages of 17 and 20. It tracks his relationship to masculinity, the pressure of youth and culture, living under the weight of his mother’s illness, his father’s absence, and his own mental health.

THE TOUGHENING

In this song, the boy’s mother is diagnosed with a terminal illness, and his father has moved away. He calls his dad looking for comfort, but instead encounters the pressure to ‘man up’ – to deal with the grief and fear in a traditionally masculine way. The boy tries to express himself, but he can’t really do it, and his dad’s energy overpowers him. I tried to emphasise the juxtaposition between the two archetypes: the mother’s softness and the father’s toughness.

I thought about this sonically as well. In my mind, the mother’s fragility is represented by the mandolin – delicate, vulnerable and constant – while the father’s hardness comes through in the snare drum, rigid and brash.

EVERYTHINGLESSNESS

The boy’s first panic attack. The first moment when something properly breaks. His body goes haywire, his brain can’t keep up: “What the fuck is happening? Am I dying? Is this a heart attack?” I remember that moment so clearly for myself. It was the first time I realised I wasn’t experiencing being alive in the same way as everyone else. That there was something slightly off about my relationship to existence, like I had a problem with living.

The song only has five lines. Everything else I tried to add took something away. Any attempt to explain it or contextualise the feeling felt dishonest.

Panic doesn’t arrive with narrative; it arrives as an interruption, which I tried to replicate musically with those big sonic stabs in the second verse. There’s a track called Disarray by Low, which we were listening to a lot. That production was an influence on this song for sure.

Around the time I was writing it, my friend Oli was in a very bad place: depressed, anxious, barely coping. He sent me a series of voice notes, and in them, he was trying to describe what it felt like. In one of them, he says, “It’s like a hopelessness… a pointlessness…” and then stops himself. “Actually, no – it’s like an everythinglessness.” That word felt completely right to me. Because it’s not that one thing is missing, it’s that everything is. Meaning, weight, future, purpose. If you’ve been there, I think you recognise it immediately.

I took the panicked breaths from those voice notes and looped them, and the track grew out from there. You can hear the anxiety in it: the lack of resolution, the constant tension. The background crackle from those recordings runs throughout the album, almost like a nervous system underneath the songs.

PLEASE DON’T TELL MY MOTHER

Please Don’t Tell My Mother is hard to talk about, and it was hard to write. It sits at a point in the album where the boy is slipping further down the spiral, and I needed some distance from it to be able to say anything at all. I originally wrote it as a poem, and later I changed every “I” to “he”. That felt important, like a way of observing him rather than writing from the first person.

The hymn at the end of the track comes from my ex’s grandad’s funeral. He had written an original hymn that had never been performed before, and a choir sang it in the church. I remember being overwhelmed by it. It made me feel like we were all completely insignificant, and yet somehow these deeply meaningful beings at the same time.

I recorded it on my phone, which felt intrusive in the moment, but it also felt vital that someone captured that small, fleeting piece of time. The family were incredibly generous and supportive about me using it on the album. Including it felt less like a quotation and more like preservation; a quiet acknowledgement of how fragile and sacred certain moments are, especially when everything else feels like it’s falling apart.

SIGNS OF LIFE

In this song, the boy goes to the pharmacy to pick up his prescription of antidepressants after the suicide attempt. Embarrassed and self-conscious, he meets a girl doing the same. They bunk off school, jump on a train, and spend a day together: smoking, jumping in rivers, and falling in love. It’s a song about outsiders, the sense of finding connection in unlikely places.

The chorus captures that raw teenage love and defiance, which I really love: “She said, let’s get out of here, do some living while we’re young; I’m sick of everything, you’re sick of everyone.”

This was another track that Brad really transformed. I sent him a piano song – which you can still hear in the opening bars – and he added dreamy synths and electronic elements, which makes it feel nostalgic and reflects the feeling of fleeting freedom and youthful escape. I think of it as a road movie.

THESE ARE THE DAYS

This song sits in the halcyon early days of a relationship. On the surface, it’s warm and tender, but underneath, it’s about two people holding onto each other a little too tightly. They become co-dependent, spending every night indoors together, smoking weed, eating takeaways, and playing PlayStation. It’s comfortable and addictive, but quietly isolating.

The boy gets lost in the fog of the relationship. It becomes the only place that feels okay, so everything else is pushed away. He neglects his unwell mother, pushing her to the back of his mind, not out of cruelty but out of self-preservation. He’s been given too much to handle. Forgetting starts to feel easier than facing what’s waiting outside the room.

I wanted the song to feel intimate, so I recorded it in my living room with the TV left on in the background. The guitar tuning was really important; it’s tuned to an open chord, and there’s a capo on the tenth fret, but the low string is left open, so it creates this soft, slightly soporific loop that never quite resolves. The part just goes round and round, which mirrors the feeling I was trying to capture: being stuck in new love, wading through honey.

Alexander Wolfe: “I’m not embarrassed to admit that I cried at my own song. That’s a first for me.”

INTERLUDE

This is another ambient piece, structurally similar to the prelude. It’s less of a song and more of a pause in the album. The track is built around a voicemail from my mum, asking me to call her back and telling me about a hospital visit. While I was making the record, she was in and out of hospital a lot. Including the voicemail felt uncomfortable, but I like uncomfortable. Those messages were part of the background noise of my life at the time.

TALK

Talk is the point where the boy’s demons start creeping back in. The new love isn’t enough on its own anymore. In the chorus, he’s being spoken to by his girlfriend. She’s encouraging him to open up, “I don’t know what to tell you, man, all I know is what you’ve got to do is talk.” It’s about how men are taught not to talk about their problems or feelings, and the quiet damage that does over time. I wanted to convey a sense that, unless something changes, that silence is going to be his undoing.

As soon as I started writing the riff, I knew this was going to be an important song on the album. It felt different to the others – more direct, more outward-facing. I wanted it to be a little more universal, less bound to a single moment, because the issue it’s circling is so widely shared.

The song was partly a reaction to a statistic I came across about suicide being the leading cause of death among men under fifty. That blew me away, the idea that the most likely thing to kill me was me. It made the idea of not talking, of swallowing things down and carrying on, feel not just unhealthy, but genuinely dangerous.

TO FEEL LOVE

This song is about escapism – the urge to run from your problems or boredom by going out and getting wasted, a trap I know all too well. After months of staying in, cocooned in new love, the boy starts to feel restless. The dopamine from the relationship is fading, and he seeks it elsewhere. He goes out with his mates, takes Ecstasy, stays out all night, and hooks up with another girl. The track ends at 5am.

It reflects that endless search for love, excitement, and distraction, and how it can lead you astray. Musically and structurally, I wanted the rhythm and energy to mirror that sense of recklessness – that kind of late-night, dizzying urgency. I leant into some more obvious indie-music production on this one. I wanted it to feel like a pop song with a soaring chorus, so then, when it disintegrates into the dark outro, you get that feeling where the drugs wear off, and you’re left with that emptiness. There’s a real voice note over the outro from my mate Leo.

21 MISSED CALLS

After the chaos of To Feel Love, the boy wakes up, hungover and guilt-ridden and checks his phone. He has 21 missed calls. His mother is in hospital.

I recorded it on an out-of-tune piano in an old house in Portsmouth, with the windows open. You can hear the birds singing in the background. It’s a short song, only a minute long, but it’s one of my favourites on the album. The weight of the moment didn’t need ornamentation. Everything else would have taken away from it.

HER FINAL BREATH

He rushes to the hospital; his mum is dying in a hospital bed. This is the boy’s last conversation with her. I wanted her to be full of love and wisdom, to have depth and warmth even in the face of loss.

I listened back to the album a few days ago for the first time in about a year – the second verse really got me, the moment where she says, “And I know about the bathtub, and yes, the darkness sometimes wins. No, I’m not angry with you, baby, you just can’t do it again.” I’m not embarrassed to admit that I cried at my own song. That’s a first for me. It was the unconditional love that got me.

From a songwriting perspective, the piano part was important. The looping right-hand arpeggiating around that E minor while the bass notes move mirrors the urgency of the boy racing to the hospital, full of anticipation and dread. The simplicity and repetition of the pattern allow the words to breathe, hopefully letting the emotional weight of the moment resonate.

REQUIEM

Initially, Requiem was just the outro of Her Final Breath, but I realised it deserved its own space. It is meant to be a sonic interpretation of her soul slowly disintegrating, moving beyond the body, going wherever we go when we die. For me, it’s the culmination of the story.

I sent an early version to my friend Joe Harvey-Whyte, who’s an incredible musician, and he added those beautiful pedal steel loops and textures. His playing is all over the album, but here it felt especially poignant, ethereal, haunting, and expansive. I had this video of a sphere digitally coming apart that I was watching on a loop while I was making it.

THE SOFTENING

The final song, The Softening, is a companion piece to The Toughening. The boy meets his dad on the beach to scatter his mother’s ashes. His father starts to fall back into some of the familiar rhetoric about being a man, and finally, the boy doesn’t shrink or stay silent. Instead, he tells his dad exactly what kind of man he wants to be.

He explains that through all the loss, pain, and difficulty, the only way he’s managed to be okay is by rejecting the masculine tropes his father embodied earlier in the album, and embracing the softer lessons he learned from his mother. Musically, the song shifts into a major key at this point, mirroring the courage it takes for him to finally say what he’s been carrying.

The lyric feels like a manifesto for the record: “I wanna tell stories, I want to fall from above / I wanna cry in the shoulders of the people I love / I’m tired of pretending I’m strong all the time / I think I’ve felt ashamed for my entire life… Every problem I’ve got is ’cause I thickened my skin / when what I needed was to be soft enough to let the light in.” He tells his dad that the pressure to be tough came from care, but that it almost killed him. His dad listens. Something has shifted.

Related Articles