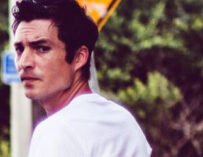

Scarlet Rebels’ Wayne Doyle: “I can be a bit more expressive when I’m writing off my own back with an idea that I’ve come up with.” Photo: Rob Blackham

The frontman and chief songwriter of rockers Scarlet Rebels takes a deep dive into new album ‘Where The Colours Meet’

Having already hoisted their flag into the UK Top 10 with their previous album See Through Blue, South Wales’ Scarlet Rebels are poised to soar even higher with the release of new album Where The Colours Meet. Led by frontman Wayne Doyle, the band has carved out a reputation for delivering powerful rock anthems. Channelling the best of classic rock but never failing to build from the foundations of solid songwriting, its music that chooses its accoutrements wisely.

Working with producers Colin Richardson and Chris Clancy and finding inspiration in themes of unity and resilience in an increasingly divided world, Where The Colours Meet also marks a new chapter for the band. Lead single, Secret Drug, is a driving, anthemic number that marries Scarlet Rebels’ classic rock influences with a contemporary edge. It Was Beautiful offers a poignant reflection on the fleeting nature of “the good old days,” blending moments of introspection with a soaring chorus, while How Much Is Enough draws from the band’s characteristic social consciousness, critiquing economic inequalities and corporate greed.

Other high points include collaborations with the award-winning blues artist Elles Bailey, Out Of Time, and Ricky Warwick (Black Star Riders, The Almighty) on the high-energy closing track My House My Rules. An album rich with melodic charm and lyrical depth, we were excited to speak with Doyle and find out more…

Did you intentionally set out to write a more unifying album than See Through Blue?

“I don’t think it was intentional at the get-go. When See Through Blue was being written, it was the height of the pandemic. Things just didn’t ring right with me in terms of what I was seeing, with people trying to donate PPE to hospitals and the government refusing it due to all the contracts that they handed out. That inspired me to go down the route with See Through Blue.

“In terms of songwriting, I write what I see and how I feel at the time. I think there are one or two political songs on this record. When I look back at the songs that we chose, they were more about relationships, mental health, longing for times gone, and that kind of thing. So, it wasn’t a conscious decision for me to be writing in a certain manner, it was more that it just happened.”

Can you talk us through the creation of a typical Scarlet Rebels song?

“It depends really, in terms of whether it’s a song that I’ve written on my own, or if it’s one that I’ve collaborated with Chris [Jones – guitarist], or even with Elles Bailey and Ricky Warwick on this album. If it’s between Chris and myself, he will give me a riff to work from. Then, I take that riff and work out the melodies and the lyrics for it.

“For example, with Secret Drug… I’ve got a tendency to make notes in my phone. If I’m in bed late at night, or out and about doing stuff, and then randomly a line comes, or somebody says something to me that might spark an idea, I’ll make a note of it on my phone and carry on. Then, when I go to write, one of those lines might appear.”

Can you tell us more about the writing of Secret Drug?

“I was watching a TV programme and somebody said something about how they’ve got a chemical dependency, and I thought, ‘That’s a nice line.’ So then I wrote in my phone, ‘I’ve got a chemical dependency,’ and that was it. Then, when we were jamming up Secret Drug, I went to sing some melody lines and that was the first thing that came out of my mouth. That led to, ‘She’s my secret drug.’

“When I was firming up the lyric, I didn’t really want to get the song not played on radio because it sounds like I’ve got a drug habit, so I changed it to, ‘I ain’t got a chemical dependency.’”

Any other examples of how it can work?

“Chris will always look to write songs that get people moving physically, that people can tap their foot along to and jump along to, whereas my tendency is to try and move people emotionally. So when we have that balance, for example a song like Grace – it’s got that really nice beat but the song itself, lyrically, can pull people in on an emotional basis.

“That’s a traditional Scarlet Rebels song really, in terms of between us. Then, I will also sit and write with my guitar, or on piano sometimes. It Was Beautiful… Have you seen the American Office? There’s a scene in it where one of the characters [Andy Bernard] says, ‘I wish there was a way to know you’re in the good old days before you’ve actually left them.’

“That was a really nice thought that I could use as a template to write a song about longing for a time that’s gone. I sat and wrote the lyrics and the melody and came up with the chords as I was doing it. It just flowed really. So it depends if I’m doing it on my own or if I’m doing it with somebody else.”

When you’ve got that one line that you’ve sung into your voice notes and you’re then listening to the track or a riff, do the other lyrics flow from there and you’re able to write them on the spot?

“It can be that, if that lyric comes out and then that’s the path that the song will go in. So, the fact that on Secret Drug I was mentioning a chemical dependency, I thought in my head that it would be about an addiction of some kind. That steered it in that way. It can be as simple as that; one line that I like will form the basis of a whole universe that I create.”

How much do you then edit and hone them?

“It depends how much they fit and how much they make sense, and if they flow properly. I do think about them a lot. Sometimes they’ve had total rewrites and others, I’ve been quite happy with how they are.

“With Secret Drug, it was only really that one change. I got the, ‘I ain’t got a chemical dependency,’ and then needed to fit certain syllables in because this was the melody that I was gonna go with. So I needed to have certain words that fit.

“The song then has a starting point, where the chorus is gonna kick in, where the bridge is gonna be, so I’m restricted in what I can fit within that structure, because it’s already been firmed up with the band. Whereas, when I’m writing on my own, I will bring the song to the boys and I’ll be like, ‘This is how this goes.’ I can be a bit more expressive when I’m writing off my own back with an idea that I’ve come up with.”

Scarlet Rebels’ Wayne Doyle: “The best way to write songs is to be blatantly obvious and raw with what you’re trying to say.” Photo: Rob Blackham

Do you think someone who knows your material would be able to tell the difference between those two types of songs?

“I think everything ends up sounding like a Scarlet Rebels song, but I think some would be able to pick out the songs that Chris has had an influence over, because they’re the more guitar-driven ones. Ultimately, they all sound Scarlet Rebelsy because they’ve got my fingerprints running through them. But I think you can tell the ones that Chris has also had his fingerprints on. “We’ve got a good relationship. Like I said, he is somebody that likes to get people moving physically, and I’ve always listened to songs and songwriters that can move you emotionally with their lyrics. If we can balance that and blend that together, it’s a perfect medium for us.”

You mentioned It Was Beautiful, we read that producers Colin Richardson and Chris Clancy didn’t originally like that song as much as you’d hoped?

“Looking at it now, I can see where they were coming from. The band demoed the songs we’d written and we sent them off for them to have a first listen, to see what they wanted to record. It Was Beautiful wasn’t in their top 12 or 13. I thought it was a bit weird, because I was convinced it was going to be one of them.

“From previous records, the band has got an emotional heartstring puller on each album. I was thinking this record needed one, and this was going to be what it was, but they didn’t comment on it. So we went into the recording studio and played it for them and they were like, ‘It’s boring, it needs work.’ Lyrically and melodically it was really good, but I get what they meant, because I was almost singing the chorus the same as the verse, just in a higher range.”

How did that feel and how did that impact the song?

“This was the first time that we’d had people produce us who would have an outside influence and would say, ‘That is too long,’ or, ‘You need to cut this verse out,’ and mould the songs as we were doing them.

“I was dead keen on that being a thing. I wanted somebody to come in and be brutal. So I didn’t take offense to it, it was just a bit disappointing. I knew that, lyrically, it would resonate with people. But the last thing I want to do is be boring.”

What changes did you then make to it?

“I was sat around one evening. Everybody had gone for dinner and I was playing on a guitar trying to work it out. The chord structure we had was the same through the song, bar the bridge. So I was playing different chord structures and I was like, ‘No that’s not working, that’s not working.’ Then, everybody came back and joined me in the control room with a few guitars, strumming along. We changed the phrasing of the chorus, which changed the song into what it is now. Also, if you hear the start of the song, it doesn’t sound like the end of the song. It goes into a pop-punk second verse and chorus, and then the end is a big crescendo.”

“It’s a really satisfying feeling to have not given up on something and then see it through to what it became. When we recorded it, the drummer and bass player went home because they’d done their bits. We then had a gig in Inverness and met at the studio to then go further north. We played it to them and they were blown away.”

“The producers giving me that feedback wasn’t a dig or anything it was just them trying to get the song as good as it could be. It built a lot of trust between us as well. From that point, we were like, ‘Okay, everybody’s on the same page.’ They knew that we were open to criticism, to make the song as good as it could be. We were also comfortable that these guys knew what they were talking about.”

Is that a good lesson for a songwriter, to not be too precious about how a song and be open to suggestions?

“Absolutely. We all wanted to make the song the best it could be. It was quite early on in the session as well. We were there for a month, and I think it was the second or third day. It really cemented that relationship, them knowing that we’d be easy to work with in terms of being open to their suggestions.

“It was exactly the kind of thing that I wanted. I wanted somebody to push us, and push me. I couldn’t be happier with the way that song turned out. For me, it’s one of the highlights of the record.”

Where did the decision to work with Elles Bailey and Ricky Warwick come from and how did that change the approach to writing and recording?

“We’re fortunate really, because we’re signed to Earache. Tim [Bailey], the head of the label is our manager as well. He asked me, ‘Would you want to co-write with anybody?’ I was like, ‘I think you need to ask these names that you’re suggesting whether they’d want to co-write with me!’ Because there’s no way I was ever going to say no to writing with somebody like Elles Bailey or Ricky Warwick.

“I said, ‘If they’re up for it, I’ll do whatever it takes to make it work.’ Nothing was said for a while and then I was copied into some emails with Ricky’s manager about arranging a writing session. So I dropped Ricky an email, introduced myself, and I was like, ‘Thanks for considering it,’ and he was like ‘I’d love to.’”

How was he to write with?

“I ended up on a Zoom call with him every Tuesday for a few weeks. He was living in LA at the time. The first session, we spoke for an hour or so. He gave me ideas, I gave some of mine, and then we decided what we were going to do. We would meet every Tuesday and go through what I had done. We were sending voice notes and videos back and forth to each other and we formed the songs.

“We did the full band demos, I sent copies of those to him and he was like, ‘Maybe it would be cool if you tried this?’ We still text now, he’s constantly asking how things are going. He’s such a nice block and put me at ease straight away. It was a really nice experience. We wrote three songs and recorded one for the album [My House Rules].”

And how did it work with Elles?

“Tim was friendly with Elles and said it’d be a really good match. Again, I was like, ‘If she’s up for it, then 100%.’ I arranged to go off to Bristol to meet her. We ended up in her studio in Bristol. We had four or five hours and, for the first two-and-a-half, we were just chatting, and then it was like, ‘Shall we do some work?’

“She opened her phone and started going through her notes. I was like, ‘Funnily enough, I do that.’ We started reading lyric ideas back and forth. I’d written a song called Sorry; an apology for a relationship that had failed and I felt responsible for. I don’t think it was ever written for any reason other than a cathartic release for myself.

“I read one of the lyrics out, something along the lines of, ‘Sorry for taking what wasn’t mine.’ Elles was like, ‘What’s that about?’ I explained it and she was like, ‘Shall we use that as a point of reference for the song and build a story around it?’ That’s what we did. Within an hour we’d written this story of a couple that are going through a breakup. The first half of the song is from my character’s point of view; the second half of the song is from Elles’s character’s point of view.”

Scarlet Rebels’ Wayne Doyle: “I’ve always listened to songs and and songwriters that can move you emotionally with their lyrics.” Photo: Rob Blackham

It’s great to have both of you singing on the finished track…

“When we were recording the song, I did a guide vocal for her, as she was recording her album at the same time. We sent the stems over so she could record her part when she’d recorded her album. I hadn’t heard her performance or vocal take, it was just blank when I left. Then, when the mixes came through, we played it and I was like, ‘Blinking heck!’ Hearing Elles’s vocal on that side of it, it was incredible.

“I’d done that old cliché of, ‘I’m gonna listen to this in my car.’ So I put it on as a playlist on my car and I drove around my local town. It was the middle of January, it was cold, it was raining. The song came on and, when her vocals started, it completely took me by surprise and gave me goosebumps.”

Another song we wanted to discuss is How Much Is Enough. Do you approach a song differently when you’re talking about the state of the world?

“I’ll constantly make little chord structures and notes about songs, but I try, where an album is concerned, to make it as lyrically relevant and fresh as as possible. I don’t like to write a great deal in between albums. When I know we have an album coming up, I know I need to get my head on and write a bunch of songs which are as relevant at the time as possible.

“When this album was coming up, it was a lot of seeing people having to choose between heating their homes or feeding themselves. It was a comment on the way that the country was being run really. I was in that mode of writing, and it was a case of getting that off my chest – that question of at what point is this gonna stop. For a while it seemed like the everyday person was getting stuff taken from them constantly. Then you’ve got a small percentage of the country reaping the benefits of everybody else’s bad luck.”

Is songwriting your way of processing what’s going on around you?

“I’ve been writing songs for the best part of 20 years now and it’s only the last three or four that anybody has really heard them. So there’s a little bit of me that will write songs in the headspace of, nobody’s going to hear them anyway. So when they do end up getting out there, it’s like, ‘Oh yeah, okay, it resonates with people.’ Absolutely you want it to resonate with people, but essentially, they’re just my viewpoints of what I’m seeing and what I’m feeling, and it goes from there.”

Scarlet Rebels’ Wayne Doyle: “I’ve been writing songs for the best part of 20 years now and it’s only the last three or four that anybody has really heard them.” Photo: Rob Blackham

Does that mean that you’re able to be a little bit more honest, because you’re working from that point of thinking that nobody’s going to hear them?

“I’ve had that thing the past few years of being brutally honest and raw in my art and it resonating with people more. Even though it’s about me, it can resonate with people. A song like Out Of Time, that subject market is really raw. It’s quite brave to be that honest and hold your hands up and be like, ‘I’m sorry for what I forced you to go through.’ There have been periods where I’ve gone, ‘Do I want to be that raw and vulnerable?’ But I just try to make the best art.”

Is it that weird songwriting paradigm that the more specific you can be, the more universal a song tends to become?

“From my point of view, the best way to write songs is to be blatantly obvious and raw with what you’re trying to say. It just resonates more. Since I’ve started taking that attitude with it, I think the band has started to be heard a bit more.”

What are your hopes and expectations when releasing an album in 2024?

“Obviously, everybody wants it to be as successful as it can be in terms of selling as many albums as possible. But for me, it’s for the album to land and for people to go, ‘They are a band that write really good songs that resonate with people and touch people.’ And in ten years’ time, people still look back at it and go, ‘It was a really good record.’ Not just be confined to the year 2024, it will still touch people in 2034 and have a legacy.

“Hopefully it opens doors for us as well. There’s a lot of material on there which could fit on films and adverts. And for people to discover us and add us as one of their go-tos. As an album, it stands up really well and we’re proud of it. Hopefully people love it as much as we loved making it and it cements a place in the industry for the band, and for me as a songwriter.”

Finally, what do you think is your greatest achievement as a songwriter and what is your big songwriting ambition?

“I wouldn’t like to say that we’ve had any kind of achievements – we did have a Top 10 album and that’s really cool. In terms of ambition, it’s just be somebody that people would acknowledge as a good songwriter. For me, whatever goes on to a Scarlet Rebels album has to work acoustically as well, because it has to be about the song. I don’t want our songs to be dressed up in massive riffs. Our guitarist is one of the best in the UK, so we could easily do that, but it isn’t where we want to come from.

“We want to be a band that writes songs, and the song be at the heart of everything that we do. So, for me, for the band to be recognised as a really good songwriting band, and me to be recognised as a really good songwriter within the UK scene, that would be really cool. But we want to be as successful as we can so that we can continue to write songs and put them out for people.”

Related Articles