Bernhoft: from Norway with soul

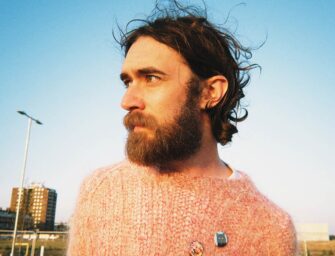

Hot on the heels of his Grammy nomination for ‘Best R&B Album’, we speak to fast-rising Norwegian soul singer Bernhoft

![]() here’s a very good chance you’ve never heard of 38-year-old Jarle Bernhoft. Or rather, there was. In his native Norway this blue-eyed soul singer is already a star, with his last two albums (2011’s Solidarity Breaks and the recently released Islander) both going to No 1. But until very recently, he’d failed to make much of an impact on the wider, world stage.

here’s a very good chance you’ve never heard of 38-year-old Jarle Bernhoft. Or rather, there was. In his native Norway this blue-eyed soul singer is already a star, with his last two albums (2011’s Solidarity Breaks and the recently released Islander) both going to No 1. But until very recently, he’d failed to make much of an impact on the wider, world stage.

That all changed the day before we rang him for a chat, with the news that Islander had been nominated for Best R&B Album at the 2015 Grammys. It’s an impressive achievement in itself, but doubly so when you realise that he’s the first non-American artist to be nominated in the 20 years that the category has been in existence.

The stage looks set, then, for Bernhoft to finally gain the attention of a global audience. But he’s certainly no overnight success. Not only is Islander his third solo studio album, before that he was a the frontman of two reasonably successful Norwegian rock bands: first Explicit Lyrics, and then – forming from the ashes of Explicit Lyrics – the more successful Span, whose two albums both went Top 10 in Norway.

With the global limelight about to shine down on this affable, intelligent multi-instrumentalist, we figured this was the perfect time to get him on the phone to discuss his musical journey so far…

How did you first get into making music?

“My dad was an opera singer and my mum was a music teacher, so I had a wide range of influences from very early on. And I was really appreciative and I think they saw some potential, so they gave me a violin when I was four, but I couldn’t really play it… it was a bit too early, I think. But I was always singing and making songs, and I remember when I was five I had a thing about the opening of Elton John’s Goodbye Yellow Brick Road. I had a cassette tape and I used to rewind it over and over again. It was that keyboard intro that really hooked me… it was mesmerising. Same with the intro to Bohemian Rhapsody… anything a bit grandiose, I loved.

“Then when I was about eight I was convinced Nik Kershaw was the best thing that had ever happened to pop music. Until I heard Michael Jackson, and then it was Michael Jackson! But I was really into guitar playing as well, I thought the guitar was just a magical instrument. So I got my first guitar when I was 12 and I got pretty good pretty fast: it’s always been my main musical instrument. I know how to play the guitar: all the other instruments, I can just fake it pretty convincingly! I have a brief history with a lot of different instruments, but I’ve always considered myself a guitar player first and foremost.”

And your musical career started in rock bands, of course…

“Yes, well I started playing in bands, but I had so many opinions on how people sang eventually I just thought, right, I’ll do it myself then! That’s always been kind of the case with any musical endeavour: I listen to other people doing music and I think, I’d have done it this way… that’s a reflection on my bass playing, my drumming, my keyboard playing, my singing.

“So that’s how I did things. And the rock thing was obviously very important to me, until, probably parallel to Span, a friend played me some Sly & The Family Stone. And it felt to me like, this is the birthplace of everything that I’ve liked about Michael Jackson and Prince. I had this sensation that I’d found out where it came from… and then digging deeper from Sly & The Family Stone, I found out where that came from. It was almost like an archaeological adventure into African and African-American music, which is kind of where I am today.

“Explicit Lyrics and Span were kind of a different musical life in one way, but what I hear is the same singer trying to sing like I do today, but having to contend with huge amps and guitarists that go to to 11. I also did a lot of session work around that time with different people: I played flute on some stuff, tuba on some stuff, bass on some stuff… and I did backing vocals as well, so it’s quite a strange discography and very mixed CV I have to show!”

Bernhoft

Span were doing pretty well… why did you quit and go solo?

“I tried to quit music, actually. I was trying to grow up and be sensible, and I started studying English Literature. I was going to become a teacher. But then during my first year at university, suddenly I was invited to play on this project and that project, and I got lured out on the road again, and I kind of just gave in after a while and went back to being a backing musician. I loved doing that: it was great to step back and not have the attention and just concentrate on playing the music.

“But I started writing songs again, and I played them to some people and they said, ‘This is pretty good.’ So I released an album and suddenly it all came together. But it was three years between quitting the band and my first solo album.”

Coming up to date, Islander sounds more traditionally soulful, less ‘pop’ than Solidarity Breaks. Would you say that’s fair?

“It’s more organic, for sure. I kind of see my three studio albums as thesis, antithesis and synthesis. The first album, Ceramik City Chronicles, was very down-to-earth, me trying to replicate 60s and 70s soul music. With Solidarity Breaks, it was like I was trying to peer into the future, using synthesizers and drum machines and every technology I could get my hands on. And it feels like Islander is kind of picking bits and pieces from both camps, but still trying to do it in an organic way. So we’ll use drum machines, but we’ll play the drum machines instead of programming them.

“All of it is played: about 50% is played live with a band in the studio and 50% is me and Paul doing overdubs and stuff. But for instance if I was going to play guitar on a track, I’d always play the whole song start to finish, and we’d use whole takes rather than punching things in. Same with vocals, it was ‘Go in the studio and sing the song’, not ‘Let’s use this line from that take and that take from this line’. You can do that today quite easily, use even single words, but we ‘d just do two or three takes, decide which was the best and go with that.”

Does that explain the more organic, traditional feel?

“Partly I think, yes, but also I was very aware when I was writing the songs for Islander that I wanted a more organic, played approach. It’s not that the experience of making Solidarity Breaks was negative, far from it, I just wanted stuff to be more organically played than sequenced this time around.”

The track No Us No Them is a duet with Jill Scott. How did that come about?

“I met Jill at the Nobel Peace Prize concert in 2011. We were both there and I’m a huge fan of hers, and it turned out she liked my stuff as well. So then I had this idea that it would be really cool to write a song as a duet. I had her in mind when I sat down with David, my trusted keyboard player, and wrote it, but then a week before mixing I still hadn’t been able to cut Jill’s vocal. So I flew to LA and we did it one day and I flew back on the red-eye flight! I like to be hands-on like that… to make sure things are happening.”

Islander also comes as a very impressive smartphone/tablet app… what was the thinking behind taking that approach?

“It wasn’t my idea, the developers had the blueprint for the app already and they approached me and said, would you be interested in doing something like this? I was flabbergasted because in a way it’s quite an old school way of presenting an album, it’s almost like a gatefold sleeve, at the same time as being extremely modern with high resolution digital files and all the rest of it. So that mix of old school and new school fitted my project like a glove.”

“My first Glastonbury show was bit useless”

You played at Glastonbury this summer, how was that?

“I was just thrilled to go there, because I’d never been. It was very muddy, but I had my wellies with me so that was okay. I got there and I was scheduled to do three gigs, but then a BBC appearance came up so there were four in total. And the first gig was a bit useless… I was doing an afternoon slot in a tent that could hold 1,500 people and there were about 150 there, mostly lying down at the back being hungover, and the only ones standing were four Norwegian ex-pats waving flags!

“But it picked up and the other gigs were really good, and the BBC appearance made it definitely worthwhile. But it was more the experience of being there, and seeing how this enormous, classic festival works. It’s the benchmark of a festival, I think; we certainly don’t have anything like it in Norway. There are some good festivals but they’re more specific to a particular style of music.”

Why did you call the album Islander?

“That was mostly because it was recorded on the Isle Of Wight. I was struck by the acute sense that the people who live on the Isle of Wight see themselves as islanders, it’s a very specific identity. And I was thinking that being Norwegian in the world is kind of similar, because Norway as a country has won the geopolitical lottery, really. We’ve got oil money, we’ve got a political system of welfare and social democracy, which provides a very stable environment for everyone. The way we breezed through the financial crisis and the recession compared to other countries, there are really no other European countries that have done that.

“It felt that all of a sudden Norway was kind of separate from the US and western Europe, which we’d very much been a part of. Well, we still are, but it’s still like Norway’s an island that’s moving away from the mainland. So I felt like I had to build a better boat or, you know, mend the bridge to get across. And then I realised – in fact it was quite an eerie sensation – that nearly all the songs on the album have references to boats and water and bridges.”

What was a Norwegian who lives in New York doing on the Isle of Wight?

“I went there to work with [Islander producer] Paul Butler. I liked his work with Michael Kiwanuka and also he was one of The Bees. I was such a mad fan of The Bees, and when I found out that one of them had made that magnificent-sounding Kiwanuka album I was like, I need to meet this guy! So I flew to London, drove down to the Isle of Wight to meet him and it was just one of those magical things where, within five minutes we were like brothers.

“I went there with the goal to make three or four recordings over the summer, but suddenly we had a whole album. It was pretty amazing, actually.”

Bernhoft

Let’s talk about your songwriting. Are you someone who writes all the time, or are you someone who’ll take themselves off for a week and write an album in one go?

“The latter, but it’s more like I’m going away for a week and writing half a song. I’m really slow at it! But at the same time, it’s almost like I feel I don’t write songs, I walk them. I go out walking and normally it’ll start with a rhythmic structure, like a small riff or something, and then if it sticks I’ll start to elaborate on it when I get back, sit down in the studio and record some bits and pieces. Slowly start to build it. That’s normally how it works.

“With No Us And No Them, it was a piano thing. I was actually trying to play Golden Lady by Stevie Wonder one day, but I kept missing the second chord, and I thought, oh that sounds okay! So sometimes it’s a fluke. It can be really random, but the normal tendency is for me to go out walking and have some kind of idea fluttering through my mind.”

When you do start to elaborate on your ideas, how do you do it? What instrument do you reach for first?

“That depends. I have a Roland Octopad that’s really fun to play with, so I might start by recording a four-bar pattern on that. Then I’ll stretch it out and see what I can lay on top, maybe improvise some stuff on a piano or a guitar. Even a bass – I think the bass is a really good songwriting tool.”

“The guitar is the only instrument where I’m conscious what I’m doing”

Do you think the fact you can play so many instruments helps your songwriting?

“Yes, I think so, because guitar is the only instrument where I’m really conscious what I’m doing, and that’s a double-edged sword: if I know what I’m doing, I’m always pushing for some new chord structrure that I haven’t heard before. Whereas if I’m on a piano, I don’t know what I’m doing, I just go for what sounds right. So I think a good combination of the two is a cool thing.”

What about the lyrics? At what stage do those get written?

“Normally I’ll try and write it all at the same time, because it’s a reflection of what you’re thinking about at that stage. And I might go totally free-flow, stream of consciousness, do a couple of verses and a chorus, and then try and interpret what I’m writing about, and try and finish it. It’s almost like you just put stuff in a bag and see what you can make out of it.”

So you don’t have a folder stuffed full of lyrics to reach for?

“No, not at all. Very rarely do the lyrics come first: they either come with the music, or at the very end of the process.”

Speaking of lyrics, have you always written in English?

“I have. I’ve tried on a number of occasions singing in my native tongue, but it sounds horrible! Whereas I feel like I can do something if I sing in English. It’s very strange. I do love the language, though, it’s such a rich language compared to Norwegian.”

Bernhoft

You’re already a pretty big star in Norway, with two No 1 albums. How’s fame treating you so far?

“It felt weird in a way when Solidarity Breaks went to No 1. I was cautious because my son was only a year old at the time, and I was thinking that, if I want to go to the playground with him, I want to be his Dad, not this… public figure. And at one point it was a bit mental, or as mental as it can get in Norway, with people wanting autographs and selfies and so on.

“But at the same time no-one approached me that didn’t like me, all the people that wanted a photo or wanted to have a chat, they were really positive. So that part of celebrity life, I don’t mind; if people want to throw rotten eggs at me, well, that’s a different story, isn’t it?

Now, with the Grammy nomination, are you prepared for that on a global scale?

“It will come when and if it comes – if you try and force it, it won’t work. At my stage in my life, I’m really happy doing… all right. As long as I can go out and play gigs where I feel I’m doing my best, that’s what I really want to do. And in time, chart success will come, or it won’t come. What I do is not try to create success, but try to create music. That’s a very important distinction to me. It’s like I’m not in for chart success, I’m in for the long term.”

So far, you’ve been in two rock bands and you’ve made three solo albums that mix soul and pop to varying degrees. What comes next, musically?

“I don’t know! Is it going to be Everly Brothers, country-style music? Is it going to be free jazz? I’m really not sure. That’s the cool thing, I feel like I can do a lot of things. Having a Grammy nomination is a huge pat on the back and it gives you a sense that you can do stuff and it’ll be appreciated. But at the same time, there’s something about the soul music that I think will never let go of me.

“See, I was all set to move away from Islander and concentrate on songwriting right now, but then suddenly the Grammy nomination gave it a new life. So I’m a bit confused at the moment, because I thought I was going one way and life has suddenly just pulled a U-turn on me! I’m not sure what happens next, but that’s exciting. Maybe I’ll resurface as a harmonica player.”

“I have tons of stuff to write about, I just need to channel it”

When will you start writing for the next album?

“It’s already in the works… the whole experience of living in America in these times is interesting and I think that’s bound to come out in some songs. I’m really thinking about what to do with that experience, especially as there’s so much going on in America right now, in terms of racial tensions and violence. It gives a whole new perspective on the recent debate about whether to arm the police in Norway, too. There’s a lot of political stuff that I’ve been reflecting on. It feels like I have tons of stuff to write about, I just need to channel it, so I think the process will go very swiftly once I sit down.

“But my home studio is in Norway, my flat in New York isn’t really suited for recording, so it’ll have to be a different way of working. And that might be a good thing, too.”

Finally, you’re the first European artist to be nominated for an R&B Grammy in the 20 years there’s been one. Given the current racial tensions in America that you’ve talked about, how’s being a white soul singer panning out for you?

“It depends who you’re talking to. I think if you asked Azalea Banks, she’d probably say I’m stealing black culture. If you ask Jill Scott, she’d say good music is good music, it shouldn’t matter what colour skin you have. I’m of the latter persuasion myself: it shouldn’t really matter. If you think colour matters, you’re essentially being a racist… but at the same time, it is an issue for some people and I’m aware of that.

“It’s a blow for me, because I’ve always been an optimist on mankind’s behalf, and I honestly thought America had moved on a long way from 1992 and Rodney King and riots in LA. And suddenly Ferguson, Missouri’s on fire and there’s the Eric Garner case in New York, it’s flaring up nationwide and I’ve kind of gone from optimist to pessimist. But I think if you have people insisisting ‘We are different, we are separate’, I don’t think that’s very helpful.”

Interview: Russell Deeks

Bernhoft’s third album Islander is out now. As mentioned above, it’s also available as a rather snazzy mobile app, which Jarle demonstrates in the video below. For more information, visit his official website, or follow him on Facebook and Twitter.

Related Articles