In this exclusive extract from his memoirs, veteran songwriter Andy Halmay reveals how he came to write for Carl Perkins

Not every songwriter harbours ambitions of pop stardom. The music industry employs thousands of songwriters who are content to toil away behind the scenes – and for over 60 years, Andy Halmay was one of them, writing hit singles for 1950s stars like Lilian Briggs and Eddie Fontaine, as well as advertising jingles and song-and-dance numbers for TV light entertainment shows.

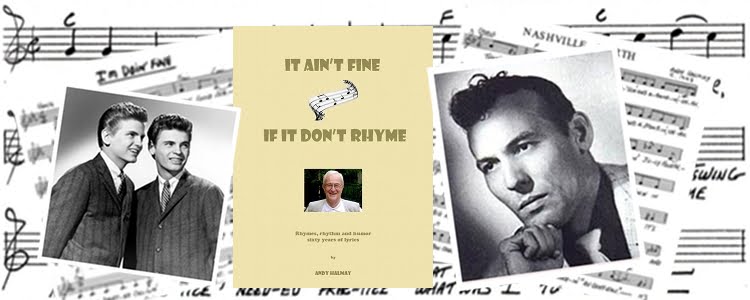

Andy, now in his 80s, recently published his musical memoirs. It Ain’t Fine If It Don’t Rhyme is available as an e-book from Amazon, and is full of fascinating reminiscences that give a real insider’s glimpse into how the music industry worked in days gone by.

Here, Songwriting presents an exclusive extract from Andy’s book, in which he recalls how the birth of rock & roll shook up the songwriting industry, and how one of his songs ended up being recorded by Carl Perkins – the legendary rockabilly pioneer whose Blue Suede Shoes was later a big hit for Elvis Presley.

![]() n the 1930s and 40s musical styles didn’t change dramatically, which made it possible for a popular song to remain popular for much longer. Singers could remain popular for longer, too. But in the late 1940s and 50s, dramatic changes took place that confused the whole industry.

n the 1930s and 40s musical styles didn’t change dramatically, which made it possible for a popular song to remain popular for much longer. Singers could remain popular for longer, too. But in the late 1940s and 50s, dramatic changes took place that confused the whole industry.

The growth of the record industry and the proliferation of AM and FM radio stations gave the music industry a parallel to the fast-moving stock market. What was hot in the morning, could be cold as ice by dusk. In the mid-1950s on a visit back to Toronto, Earl Parnes, a fellow writer and old friend introduced me to an act he was managing – the Hi-Lites. I loved their act, brought them down to New York and recorded them. When I started marketing my masters, I was in for a shock. One A&R man at a major label had seen them and asked me to rush copies of the new records to him. Then he called me back to say that if I had brought these in two weeks earlier he would have given us a beautiful record deal. As it was, he concluded they were passé.

The economics of touring big swing bands with 10, 12, and even 18 musicians no longer worked. Also there was so much copying of style that an original twist or arrangement would so quickly be emulated by so many that in no time the original would be drowned by the copies, rendering all to be soundalike clichés. Swing died and for a few years it was replaced by nothing. Jazz, which had been growing, went off into styles so sophisticated as to lose the large audience and hang on the ledge by its fingertips with a limited following. Mitch Miller tried various new approaches in pop but didn’t make it.

“The kids liked the simple sounds of rhythm and blues”

And then the kids took over. They liked the simple, downright amateurish sounds of rhythm and blues and a new ‘trend’ was established. Publishers and A&R men at record companies were groping like blindfolded men in a maze, always sniffing for the next trend.

The Everly Brothers

Apparently, Acuff-Rose, music publishers and managers, had insisted that all material recorded by the Everlys had to come from them. Jack Newman was calling me to find out if I had any new material that might be suitable for the Everlys. I’ve always been honest and outspoken. I told Jack that I hadn’t been writing lately and that I didn’t dig the Everly Brothers or their material. I wouldn’t know what to write for them.

Jack asked if I was sure I had nothing new and then I recalled that, yes, I’d been toying with a song about a kid who is bugging his dad for the keys to the family car. I titled it Pop, Let Me Have the Car. That got Jack interested.

“I was in my late 20s and that already had me over the hill”

I chuckled as I told him that I had scratched my head for a teen theme. I was in my late 20s and that already had me over the hill as far as mentalities that buy a lot of records were concerned. I had recalled how in my teens I would come up with all sorts of far-fetched arguments to get dad to let me have the car for a night. Jack wanted to hear what I had and I recited a couple of verses and even hummed a simple melody.

“You finish that song tonight and come in to see me first thing in the morning,” Jack ordered me. That got me off my butt. I can’t notate so all I brought him was the lyric which I sang for him without accompaniment. That was good enough for him.

“We’ve got to record a demo on this right away,” said Jack. He asked me if I knew any singer who might be right for the demo. I shrugged and just then we saw a young man with a guitar slung over his back pass by in the hall outside. “Grab that fellow,” said Jack. “That’s Eddie Fontaine. He’ll be perfect for this.”

Eddie Fontaine

He had a very self- assured and positive manner about him and I said okay. He then strummed and hummed and fiddled, and changed a few words and a few notes. It wasn’t a great change but it was an improvement and that satisfied me.

Once we recorded it, he said, “Now let’s go out and peddle this song to other publishers and see who’ll give us the best deal.”

I was shocked. “Jack paid for this demo,” I said, “What’s the matter with you?”

Eddie shrugged, “Okay, then let’s get an advance out of Jack.”

I was innocent and naïve enough not to have even thought of asking for an advance. In Jack’s office Eddie went into a song and dance about having a starving baby at home and needing funds badly. Jack happily gave us $100 each which is the equivalent of about $770 today.

Several weeks later, Jack called me to inform that Carl Perkins, the Blue Suede Shoes man, had recorded Pop, Let Me Have the Car on Columbia Records.

Want to know more? Then buy Andy’s book from Amazon.com!

Or if you were wondering what the song sounded like…

Related Articles