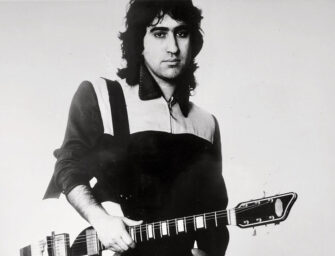

The Blue Aeroplanes’ Gerard Langley: “I thought ‘I’ve got to learn to do this myself’”

BIMM’s head of songwriting and speak-singing leader of Bristol’s enduring art rock band talks about the 80s, poetry and stagecraft

Bristol art rock band The Blue Aeroplanes emerged in 1981 and haven’t stopped plugging away, driven by an uncompromisingly eclectic style and the songwriting sensibility of group leader Gerard Langley, who also finds time to teach the discipline at the local BIMM music college. Combining banjos and mandolins with scratchy post-punk guitars, and joined by a DJ and male dancer onstage, the Aeroplanes were always considered a maverick band. And yet, with Courtney Barnett, Kate Tempest and George The Poet breaking through in recent years, Gerard’s trademark speak-singing is now part of the mainstream.

In fact, Michael Stipe wrote that he only decided to deliver the spoken singing-style vocals on E-Bow The Letter after watching Gerard on tour. And the R.E.M frontman wasn’t the only highly regarded musician to be influenced by the Bristol band: Manic Street Preachers’ James Dean Bradfield revealed that the Aeroplanes were the best live band he had ever seen and the reason the Manics decided to move around on stage.

Songwriting met up with Gerard in our mutual home city in January, the month that not only saw the first new Blue Aeroplanes album since 2011’s Anti-Gravity but also the publication of his Selected Poems & Lyrics…

Take us back to the beginning, before The Blue Aeroplanes. How did you get into writing?

“I left college at 20/21 and I went to a punk gig. This kid comes up to me and says the one of the strangest lines I have ever heard: ‘You look like Mick Jones out of The Clash, do you want to come to a poetry gig?’ I had done the university magazine, had done numerous interviews and articles. So I had some poems and there this was this group that met every Tuesday. The guy who ran it organised for all the groups to perform at a festival. I had seen The Cortinas there the year before and that audience was mainly bikers, so I thought, ‘I am not going to read a bunch of poems out to some bikers’.

“I had this friend from Sheffield who used to just go out dancing, and he had a friend who’d just moved to Bristol with his girlfriend. He played guitar so I went round his house and said, ‘Do you fancy playing a bit of guitar with words/music?’ He said, ‘When?’, and I said, ‘Tomorrow!’. He worked out some John Martyn-esque echo guitar and it was just a one-off. Two bands, immediately after the performance, came up to and asked if we could support them.

“We supported everybody, then started to build up a following, so we made an album afterwards, but that line-up split up. I didn’t like the fact that this one guy, Jonjo, wrote all the stuff in the band. He was very good at it, but he wanted to be a proper singer-songwriter, so I thought, ‘I’ve got to learn to do this myself’.”

What is the writing process you go through?

“We just bring in riffs/ideas and we kick them around until they have taken some shape. I start using words that I have written, fitting the words to the tunes or riffs that we’ve come up with. In The Blue Aeroplanes that is what I have always done.”

Do you go into jam sessions with preconceived ideas and preparation?

“Over a period of time I’ll have about 30 or 40 finished poems. Sometimes I’ll take a particular poem and fit it to a piece of music and I’ll make the band play longer or shorter to fit the words. Other times, a song will be half-finished and I will write it to the music. I used to make a distinction between the two, some were poems and some were lyrics. However, in the end, even when I write a poem, I know I am liable to do it over a piece of music, and when I write a lyric it can be as poetic as I want. That distinction is a lot more blurred.”

What’s your take on that argument generally? Are poetry and lyrics separate or homogenous?

“People basically don’t know what they’re talking about, because 95% of literary criticism is written by people who don’t know anything about pop music. They’ve been to public school or Oxbridge and have never listened to pop music before. They think pop music is all chart stuff. On the other hand, most rock music critics are not writers; they are journalists. When Bob Dylan was nominated for his Nobel Prize, there was constant debate on the radio on that subject for two days. The way prose and lyrics are written are the same, the complication is that 20th Century poetry is largely dominated by free verse and blank verse. TS Eliot’s The Wasteland is the first modernist poem, where he dispensed with regular meter and rhyme schemes.

“A sonnet is written to a very specific form; most poetry up until the 20th Century used tight rhyme schemes and rhythm, such as iambic pentameter. With that you are fitting your words to a very precise metric, and if you do it badly, it sounds very repetitive. So the art of it is how to use those stress patterns creatively to make it not sound too ‘sing-songy’. With a song, you do exactly the same thing, except not only are there stress patterns but there are melodic note choices that affect your choice of words. However, it is the same way of working as writing a piece of poetry.”

The Blue Aeroplanes: “Never admit fear. If you make a mistake on stage, ignore it and make it look deliberate.”

When it came to producing a book of poetry, which is coming out soon, are those part of the pile of parts of lyrics, that haven’t turned into lyrics?

“Most of this stuff is selective and is on record, but there is some I never found the right piece of music for. I did some straight poetry reading when I was about 21/22, but they’re fairly boring, certainly comparing it to playing with three electric guitars. I kind of decided not to bother and stayed in my area.

“I still do write most of them, so 80 or 90 percent roughly were completed as poems first. The reason why the big poets [in America] could perform their work so well to jazz was that in the poems themselves, along with Hollywood, jazz was also influential at that time. They incorporated the rhythms of jazz into the poems they performed.

“In my poems one of the major influences, along with advertising and journalism, is pop music. Therefore, I am incorporating them. There are people like Kate Tempest/George The Poet doing the spoken word, and even Courtney Barnett, so listening to my stuff it’s not as weird. There are a lot of people doing that now, which was much different when I first started. It kind of fits into what’s almost a scene in and of itself.”

Did you feel marginalised geographically and possibly musically because of being from Bristol? Did you feel a part of the London scene?

“London’s only an hour and a half on the train, so there’s not much difference. I suppose when we were coming up we were often regarded as an odd band or an experimental band in that, during that 80s period, we were one of the only British bands using acoustic instruments. If you look at C86 or something, there’s no acoustic stuff on it at all.

“We were using mandolins and banjos. There was also Oysterband, who worked with loads of different and unique instruments. In fact I did a song called Siamese Boyfriends in 1986 with Ian Kearey [formerly of Oysterband] – he’s just produced and played on Shirley Collins’ comeback album. That connected us; the only other bands doing what we did were American bands. Post-punk bands like R.E.. were doing a similar sort of thing. The NME had this tag-line for us: ‘The best American guitar band from England’. We were always associated with those guys rather than stuff from this country. That’s why Bristol didn’t really come into it.”

What do you advise to students and people generally when it comes to the songwriting element?

“They all follow a similar path, so it’s all kind of like Bombay Bicycle Club or something like that. You have to teach them a song can be anything, because they believe a good song has to be certain things to be popular. I have to show them songs that are much weirder than that and more popular, and I say ‘check it out’. You have to write as many different styles as you can, because you don’t what you’ll be best at.”

When it comes to playing live, do you have to mentally prepare yourself?

“It’s a part of what I do. On the day of a gig, during the day, I gradually morph into Stage Gerard, which is as unattractive as a personality as Everyday Gerard. I’ve done it such a lot. People often say, ‘Do you feel nervous?’ I think it’s very, very unlikely that any gig on this tour will be the worst gig I’ve ever done or the best I have ever done. I’ve played on the main stage at Glastonbury and Roskilde, in front of 70-80,000 people four or five times; sold out The Forum in London. None of these gigs are going to be that. I have had some complete disasters and some completely amazing gigs, but most gigs are going to be in between.”

Have you got any anecdotes of that time?

“I remember the first time we played The Forum (London). That was always the biggest gig to date. There is this big curtain and you can hear the audience baying through it. So we come out and they lift the curtain up; the first song we play is called Spitting Out Miracles. It starts with one guitar line. So we are looking round saying, ‘Where is it?’, and Alex [Lee] wasn’t on stage; he had gone to the toilet and management hadn’t noticed. So Rod comes in plays the bit that he doesn’t usually do, but misses a bit. Then the drums come in at the wrong beat. I remember thinking, ‘We’ve blown it’. We got to the end of it and audience screamed, ‘Yeah!’ Luckily I think they thought it was an experimental Captain Beefheart instrumental, but we thought afterwards, ‘We can do no wrong now’. That’s why I always say: never admit fear. If you make a mistake on stage, completely ignore it and make it look deliberate.”

Interview: Aaron Slater

The Blue Aeroplanes’ new album Welcome, Stranger! is out now. To find out more, visit theblueaeroplanes.com

Good insight to a band I rate highly. Followed them from the start and best live concerts ever at the F&F. Always found them slightly ahead of the curve.