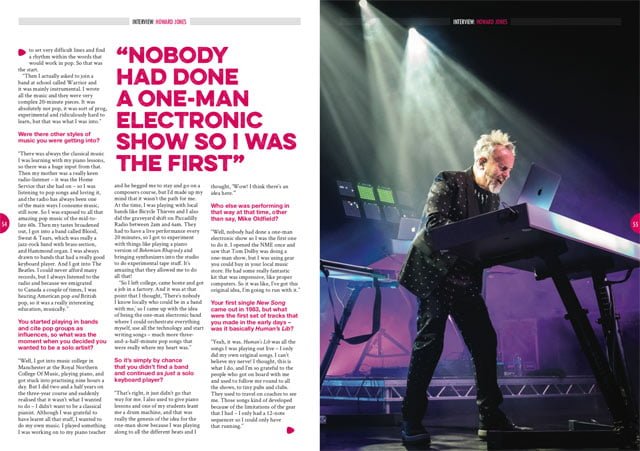

A defining figure of mid-80s synth-pop, Howard Jones reflects on his venerable career 35 years after his sudden transatlantic success

Acclaimed synthpop pioneer Howard Jones burst on the contemporary music scene in 1983 with quintessentially English songwriting, pioneering layered keyboard arrangements and thought-provoking lyrics. His very first single New Song reached No 3 on the UK singles chart and his first two albums, Human’s Lib and Dream Into Action, followed suit and brought Howard a host of hits including Things Can Only Get Better, What Is Love?, Pearl In The Shell, Like To Get To Know You Well, Hide And Seek (performed at Live Aid), Look Mama and No One Is To Blame, which reached No 1 in the US.

Howard has sold over eight million albums and continues to tour across the world every year, performing to many hundreds of thousands of music fans. He toured the UK this May, to celebrate both the release of his brand new album Transform and 35th anniversary of the release of his debut album Human’s Lib, so what better time to reminisce on his breakthrough and incredible career…

You’re well known for playing keyboards and synths. Were you immediately drawn to the piano at an early age.

“Yeah, I started playing when I was seven – my parents really wanted me to learn the piano. I hated having lessons because I wanted to be out playing football, but I got to nine and I remember hearing Puppet On A String on the radio, going to the piano and being able to pick out the tune, and being able to harmonise it, and I thought, ‘Oh, this is the most exciting thing ever in the universe!’ From then on, they couldn’t keep me off the piano. In fact, it got obsessive – four hours a day. I was a real reclusive figure, always at the piano.”

How did that develop into writing your own music and lyrics?

“My parents had emigrated to Canada so I found myself in High Wycombe and at school I met a guy who was a poet. His poetry wasn’t very song-like, it was more like prose and very interesting, but he gave me piles of his writing and asked me to set them to music, which was really difficult because it didn’t have any natural rhythm – nothing rhyming or anything like that. But I think this was really significant for me because I had to really battle to write music to go with this, so I think it stood me in good stead. If you look at my work, a lot of it is not conventionally rhyming or rhythmical, so I got into the habit of being able to set very difficult lines and find a rhythm within the words that would work in pop. So that was the start.

“Then I actually asked to join a band at school called Warrior and it was mainly instrumental. I wrote all the music and they were very complex 20-minute pieces. It was absolutely not pop, it was sort of prog, experimental and ridiculously hard to learn, but that was what I was into.”

Were there other styles of music you were getting into?

“There was always the classical music I was learning with my piano lessons, so there was a huge input from that. Then my mother was a really keen radio-listener – it was the Home Service that she had on – so I was listening to pop songs and loving it, and the radio has always been one of the main ways I consume music, still now. So I was exposed to all that amazing pop music of the mid-to-late 60s. Then my tastes broadened out, I got into a band called Blood, Sweat & Tears, which was really a jazz-rock band with brass section, and Hammond organ. I was always drawn to bands that had a really good keyboard player. And I got into The Beatles. I could never afford many records, but I always listened to the radio and because we emigrated to Canada a couple of times, I was hearing American pop and British pop, so it was a really interesting education, musically.”

You started playing in bands and cite pop groups as influences, so what was the moment when you decided you wanted to be a solo artist?

“Well, I got into music college in Manchester at the Royal Northern College Of Music, playing piano, and got stuck into practising nine hours a day. But I did two and a half years on the three-year course and suddenly realised that it wasn’t what I wanted to do – I didn’t want to be a classical pianist. Although I was grateful to have learnt all that stuff, I wanted to do my own music. I played something I was working on to my piano teacher and he begged me to stay and go on a composers course, but I’d made up my mind that it wasn’t the path for me. At the time, I was playing with local bands like Bicycle Thieves and I also did the graveyard shift on Piccadilly Radio between 2am and 6am. They had to have a live performance every 20 minutes, so I got to experiment with things like playing a piano version of Bohemian Rhapsody and bringing synthesizers into the studio to do experimental tape stuff. It’s amazing that they allowed me to do all that!

“So I left college, came home and got a job in a factory. And it was at that point that I thought, ‘There’s nobody I know locally who could be in a band with me,’ so I came up with the idea of being the one-man electronic band where I could orchestrate everything myself, use all the technology and start writing songs – much more three-and-a-half-minute pop songs that were really where my heart was.”

So it’s simply by chance that you didn’t find a band and continued as just a solo keyboard player?

“That’s right, it just didn’t go that way for me. I also used to give piano lessons and one of my students leant me a drum machine, and that was really the genesis of the idea for the one-man show because I was playing along to all the different beats and I thought, ‘Wow! I think there’s an idea here.’”

Who else was performing in that way at that time, other than say, Mike Oldfield?

“Well, nobody had done a one-man electronic show so I was the first one to do it. I opened the NME once and saw that Tom Dolby was doing a one-man show, but I was using gear you could buy in your local music store. He had some really fantastic kit that was impressive, like proper computers. So it was like, I’ve got this original idea, I’m going to run with it.”

Your first single New Song came out in 1983, but what were the first set of tracks that you made in the early days – was it basically Human’s Lib?

“Yeah, it was. Human’s Lib was all the songs I was playing out live – I only did my own original songs. I can’t believe my nerve! I thought, this is what I do, and I’m so grateful to the people who got on board with me and used to follow me round to all the shows, to tiny pubs and clubs. They used to travel on coaches to see me. Those songs kind of developed because of the limitations of the gear that I had – I only had a 12-note sequencer so I could only have that running.”

Do you think the restrictions helped you to focus your creativity? Sometimes having too many options, instruments and technology can be overwhelming.

“That’s so true. What I learnt, actually later on in my career, is that it’s really good to set yourself rules you can’t break and deliberately have parameters that you stick to for an album, otherwise it can go bananas and you’re all over the place.”

Can you give us some examples of self-imposed restrictions you’ve employed?

“There was an album I did called Ordinary Heroes which was about 10 years ago, and I said this has got to be piano, electric bass, one guitar part, vocal, backing vocal, string quartet, and that was it. It was all about arrangement and I had to stick to those instruments. And the only time I broke the rules was when I got the Morrison Orpheus choir to come in, but it was begging for it!”

Related Articles