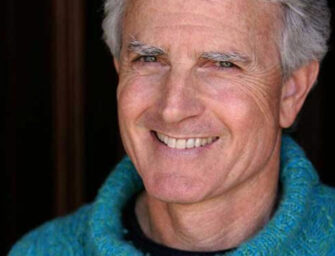

Alan Parsons: “…recording The Beatles, Pink Floyd, The Hollies and countless other artists made me a better songwriter…”

We catch up with engineer, producer and recording artist Alan Parsons ahead of his lecture series at Abbey Road Studios

Alan Parsons started his career in the 1960’s as a young in-house trainee engineer working at Abbey Road Studios on the final two albums by The Beatles, Let It Be and Abbey Road. As his experience in the studio grew so did his responsibilities and he mixed Pink Floyd’s Atom Heart Mother before progressing to engineer on their ubiquitous classic The Dark Side Of The Moon. Parsons also produced records for the likes of John Miles, Pilot and Steve Harley & Cockney Rebel, including the million-selling single Make Me Smile (Come Up and See Me).

His ever morphing career eventually led to the formation of The Alan Parsons Project in 1975, a collaboration which started when Parsons met Eric Woolfson in the Abbey Road canteen. Woolfson’s original role was as Parsons’ manager but the pair eventually realised that their shared musical vision could be best realised if they started a group of their own. Over an eleven year period the band released 10 albums of cinematic prog rock and are perhaps best known for their chugging hit Eye In The Sky (off the 1982 album of the same name).

Parsons will return to Abbey Road Studios next month to give a series of talks about the development of his own skills in the studio and the changes in technology that have shaped the recording industry over the years. We caught up with him in his California home to talk about the upcoming lectures and how he feels his career, both behind the desk and as a recording artist in his own right, helped to shape him as a songwriter…

What can you tell us about your upcoming Sleeve Notes talks?

“In November I am doing a series of lectures at Abbey Road Studios about my career as a recording artist, producer and engineer. It is being co-hosted with the journalist David Hepworth and he’ll also be helping with the Q&A part. I’m sure I’ll get lots of questions about working with The Beatles more than anything else. It will also look at different studio techniques and it should be great.

[cc_blockquote_right] IN THE BEATLES DAYS IT WAS ABSOLUTELY MY JOB TO KEEP MY MOUTH SHUT [/cc_blockquote_right]“As well as the two weekends of talks, during the week in between there will be masterclasses which will be actual recording sessions in Abbey Road. People can watch the recording process and watch me at work and ask me questions. The talks are happening in the legendary Studio Two and the masterclasses are happening at Studio Three.”Do you think the experiences you had in the studio made you a better songwriter?

“Oh I think so, experience is everything. I definitely think the experience of recording The Beatles, Pink Floyd, The Hollies and countless other artists made me a better songwriter and I think I learnt through the process of working with those people what worked and what didn’t.”

As a young in-house engineer what was it like to be in the studio with The Beatles?

“It was incredible of course, although I can’t really take any credit for the creation of Abbey Road. I was very much in training, a green young engineer who was a tape operator. That was my role, but it was an incredible experience to be with the greatest songwriters ever.”

Did you witness anything in particular that helped with your own songwriting?

“Nothing I can bring to mind. I remember Paul would come in, and this isn’t as much to do with songwriting as performance, but he would come in at two o’clock every day and sing Oh Darling and then after four or five consecutive days he finally felt like he’d got the one he was looking for. It’s a song that’s really tough on the voice. He could only sing it two or three times before it got worn out but he maintained that was what he wanted to do, try to get back to the sound of when he was singing all night every night, singing Kansas City and all those other shouting songs. In the end he got there!

“I didn’t really ever see The Beatles songwriting, they came in and would develop their songs in the studio to a large extent, but the actual writing ideas were happening elsewhere.”

Was it a similar experience with Pink Floyd?

The Dark Side Of The Moon was a very well prepared piece, the songs were all there, the lyrics were largely written. The only things which changed during the course of the recording were the production differences, the gaps between the songs, the way one song led to another, that’s what changed. They’d actually already been performing the piece as a composition called Eclipse, playing it live. It got changed to The Dark Side Of The Moon, but it was essentially the same.”

[cc_blockquote_right] I THINK A GOOD PRODUCER CAN TRANSFORM A

SONG [/cc_blockquote_right]

But you were a bit more hands on at that stage?

“Yes, I was an engineer by then and wasn’t afraid to express my opinions or pitch in ideas. In The Beatles days it was absolutely my job to keep my mouth shut.”

Do you think the role of the engineer and producer is to augment the songwriting, or is it a separate process?

“I think a good producer can transform a song. If you make a small change compositionally that really makes a song gel then you can say production is part of songwriting. For example I remember on Steve Harley’s Make Me Smile (Come Up And See Me) he was phrasing the chorus completely differently and I suggested that he made it more rhythmic and I think that is part of the hook of the whole record, so I take a bit of credit for that – although I didn’t get paid for it.”

Did your career progress from engineer to producer and then on to The Alan Parson’s Project?

“They happened almost simultaneously, I think Pilot’s Magic was creeping up the charts when Eric and I first met. Our relationship at the beginning was kind of a business relationship. He was a songwriter with some experience in the business and he knew how to make deals. He said ‘I think you need a manager’ and so he signed me up as a client. In no time at all we were working together as a songwriting and production team for the project.”

How did you share writing duties, did you work together or separately?

“I’d done very little in the way of songwriting up to that point but Eric encouraged me, he said ‘go off and see what you can come up with and record some demos’. We went to a studio in Islington called Pathway and stuck down a couple of ideas for one of the songs he had, The Raven and one of the songs I had, To One In Paradise. It was much more collaborative in the beginning than it became in later years. We tended to work more separately as writers later on.”

The legendary Studio Two at Abbey Road: where Alan Parsons will give a series of talks with the journalist David Hepworth

Was Eye In The Sky one of the songs you wrote together?

“Well I wrote the intro, Sirius and they’ve often been linked together. That actually became a sports theme for some reason, it got grabbed by the Chicago Bulls and countless other teams have used it. It’s never off the airways over here as a sports theme.

“Eye In The Sky was one of the biggest hits of the project. I think Eric did a really good job on it, but I’ve never been allowed to forget that I was not that impressed with it in the early stages. We couldn’t find a feel that I thought was working. Ultimately we ended up with this chugging thing that worked well but at one point I really was ready to throw it out. Believe it or not the same happened on Don’t Answer Me, we really struggled before I felt we had something.”

Did you find it difficult to change from your producer’s hat to your songwriting hat?

“It was an additional one really. I had two jobs already, engineering and producing, and now I had to get into compositions and then occasionally even performing. There were a lot of hats to be worn.”

Do you think they complemented each other?

“It definitely made it easier but generally speaking I always worked on instinct. I didn’t say ‘well I’m doing this as a producer’ or ‘I’m doing this a composer’, I just worked to achieve the results I was looking for.”

[cc_blockquote_right] “ANYBODY WHO CAN PLAY GUITAR OR A KEYBOARD CAN NOW RECORD A DEMO [/cc_blockquote_right]

The Alan Parsons Project were incredibly prolific, you made 10 albums in 11 years.

“We were pretty prolific, especially compared with me now. I haven’t made an album since 2004, which is a long time. We tried to put out an album once a year and it was important that we did because we didn’t have a live show to back up our act, so that’s all we did. We just made records. It was only in the mid-90s that I decided, without Eric’s support, to put a band together and go out on the road.”

Why did you originally decide not to play live?

“To be honest I think we were a little bit frightened of playing live in the early years because our music was so heavily orchestrated and involved. There were so many layers of vocals and synths and I think we would have found that we couldn’t pull it off. We were studio guys not live performers. But as technology changed synthesizers became more sophisticated, sampling became a reality for some of the orchestral sounds and we found that we could do it. It would have been much more difficult in the 80s.”

Do you think these changes in technology also drive changes in songwriting and creativity?

“I think it’s good that anyone with a computer now has recording facilities. Anybody who can play guitar or a keyboard can now record a demo, that didn’t used to be the case. If you had a cassette machine you could do a rough demo but the potential is there now with GarageBand and other software for anyone to make a decent demo. I think songwriters should feel encouraged by that and you can take things a little bit further than just the basic song, you can add harmonies. I think that’s good for songwriting. The recording process has become what songwriting is now. Songwriting, engineering, production, working with Pro Tools and shifting things around, that’s all now part of the same process.”

What are your thoughts on MP3’s and downloads?

“We’re in a rather sad state of affairs. People are listening to playlists of one artist for three minutes and then another artist for three minutes and in this appalling format, MP3. Thank goodness there seems to be a resurgence in vinyl and people caring about quality, with that comes the notion of listening to a whole side of the album. That’s coming back, it’s a lost pastime and people don’t do that anymore. With email, the internet and countless television channels people just sit in front of their computers all day.”

Why do you think that is?

“When I was growing up the DJs would be the kings. They would play the records that they liked and they would say why they liked them and that’s how the charts were assembled. Now it’s all down to Twitter and Tumblr and Instagram and Facebook to communicate musical tastes and unfortunately those musical tastes don’t usually extend to listening to more than one song of any particular artist and I think that’s terribly sad. I’m a huge supporter of high quality downloads, preferably whole albums. The quality is there on the internet, people just choose to get the fastest and least expensive way of doing it, and usually least expensive is free. This is the talk of the whole industry right now. I’m not the only one who is bitterly disappointed about artist and writer rights being wrongly exploited.”

Especially if playing live isn’t something a band want to do, it’s very hard to survive.

[cc_blockquote_right] “I COULD NOT SURVIVE WITHOUT PLAYING LIVE, IT’S MY BREAD ANDBUTTER [/cc_blockquote_right]“I’m one of those people. I could not survive without playing live, it’s my bread and butter.”

Returning to the studio, can you think of any particular examples where the limitations of technology hindered the process of creating an album?

“When we had restrictions we rose above it and we found another way of expressing what needed to be expressed. We only had four or eight tracks but we made it work, we mixed stuff down to another track, bounced things around and that had a certain magic to it and it had a commitment as well. Even on The Dark Side Of The Moon, which had 16 tracks, we often had to put bass and drum on the same track and mix the vocals down as we went. These days however many tracks you want is as many tracks as you you’ll get, it’s just a very different situation.”

The constraints almost made you think in a more creative way?

“Yes and to be honest it was more fulfilling as an engineer back then. Engineering was an important part of that decision making process, getting things balanced correctly.”

As a young engineer did you find it hard to not be overawed by the acts you were working with?

“It was very difficult with The Beatles and Paul, I never got used to the notion that I was in the same room as those people. Ironically I’m going to a fundraising dinner tomorrow for PETA, which Paul McCartney is playing at. I haven’t seen him for years but am hoping to rub shoulders with him.”

Do you often reminiscence about those days?

“Constantly, it’s something that I have to do by default because people always want to talk about The Beatles and Pink Floyd. I’m never allowed to forget it, but I’m okay with that. It was a big part of my career and ultimately why I’m here now.”

Lastly, which is the role you enjoy the most?

“I’ve always enjoyed engineering and mixing, I think that’s my main role.”

Duncan Haskell

For more information on Alan Parsons and Sleeve Notes: From Mono To Infinity visit his website alanparsonsmusic.com

Related Articles