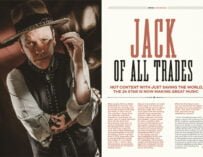

The frontwoman, actor and podcast host talks about her influences and admits she hadn’t written a song until joining Garbage

Scottish singer-songwriter Shirley Manson is best known as the iconic frontwoman for the alternative pop-rock band Garbage. But what is lesser known is that her career as a vocalist started way back in 1984 with Goodbye Mr. Mackenzie and then Angelfish in the early 90s. It was in a music video for the latter group that she was discovered by her future bandmates Butch Vig and Duke Erikson.

Garbage’s multi-platinum eponymous debut was released in 1995 and would go on to become a seminal record of the post-grunge era, propelled by a string of increasingly successful singles, such as Only Happy When It Rains, Stupid Girl and Milk. Their early critical and commercial success was followed by another five studio albums, including 1998’s multiple Grammy-nominated Version 2.0, and a greatest hits compilation in 2007.

In addition to fronting Garbage, Shirley has acted in several movies, appeared in the television series Terminator: The Sarah Connor Chronicles and also recorded vocals for the theme song for 2017 series American Gods. She has also recorded with the likes of Queens of the Stone Age and Gavin Rossdale.

Earlier this year, we spotted an advert for email marketing company Mailchimp’s new podcast series, The Jump, where Shirley interviews musicians about, “That one song that changed everything.” So we thought it only fair to turn the tables back on her and ask a few questions about her career and songwriting…

Remind us how you got the audition with Garbage.

“What happened was the three male members of Garbage had been looking for a singer and apparently, unbeknownst to me, they had approached a whole bunch of other people, but I didn’t know about this. And they had tracked me down in Scotland because Steve Marker, one of the guitarists in Garbage, had seen my band Angelfish perform on MTV at one o’clock in the morning, and he liked my voice. So he suggested to the others that they track me down, and that’s exactly what they did, and they managed to do it within 24 hours.

“My record company at the time explained to me who Butch Vig was and I was obviously really flattered and pretty excited at the chance to go and meet him. The way the whole thing was presented to me was just, ‘They’re looking for you to sing a song on their new record. It’s a producers project. Would you be interested?’ And I was like, ‘Of course I’d be interested.’ And that’s basically how it started.”

So you didn’t know who Butch Vig was, at that point?

“Well, I didn’t know him by name. Obviously, I knew the records he’d worked on, but I’ve never been one of these people to go, ‘Oooh, who produced this?’ and memorise producers’ names. It was just never part the way I approached music, in any way, shape or form. So when my record label rep said it’s the producer who worked with Nirvana, Smashing Pumpkins and Sonic Youth, of course, I knew who that was, I just wasn’t familiar with his name.”

What was your experience of writing music before joining the band?

“Well, I am unlike most professional songwriters in that I had never written a note or a word in my life, until I joined Garbage. And I was just expected to jump in as an equal member of the songwriting team. They assumed, because I’d been in a band for a decade by that point, that I was a songwriter, but in actual fact I wasn’t.

“When I went to audition for the band in the first place, I sort of blagged it and said, ‘Yeah, I can write, sure.’ So I put myself in the absolutely terrifying position of being expected to write in front of three producers and writers, and because it was like being forced to jump, I had to get it together. So what you essentially hear on the first Garbage record is some of my first attempts at ever writing anything. It’s very unusual, let’s put it that way.”

Shirley Manson in Songwriting Magazine: “I had never written a note or a word in my life, until I joined Garbage.”

How much were you involved with the songwriting process for the first album?

“It’s hard to dissect an album like that, in my opinion, but that’s just how I see it. Whether you want to look at a song like Milk where I wrote the melody and the words, or you want to look at a song like Stupid Girl where it was more or less, sonically, completely produced and I sang over the top of it and augmented some of the words. So, as I said, I was such a new member to the band, that each song was different and each song has it’s own journey, so to speak.

“I think, in a situation where you’re all in the room making a record, every decision that gets made is put under the group umbrella, so it’s difficult to dissect everybody’s influence, necessarily.”

Do you think it helped that you went into the situation without any prior writing experience, and didn’t go in with any preconceptions?

“That’s a good question, I don’t know. It’s impossible, with hindsight, to really answer that accurately. I think yes and no. There are a lot of benefits to being ignorant and then there are also benefits to having skill. I don’t think about the past like that; I feel like you do what you can do the best you can, in that moment, and then you have to move forward. It’s a useless exercise to analyse how and where and when…

“I think it’s part of the journey of an artist: you continue to grow, hopefully. Sometimes you lose things in that process and also you gain things. If you apply yourself to what you do, ultimately, in the long term, you become better at what you do. It’s like naive art, it’s the same thing, you certainly lose a lot in the journey. But that’s life isn’t it?!”

How do you feel your own songwriting process has changed and developed over the years?

“There are two things that have changed the most for me. I don’t overthink anymore, I just try to really be in the moment – which is a challenge for me, at the best of times – but I’ve certainly managed to become better at that practice in the studio, where I just try not to overthink about how people will receive it, will they understand it, has it told the story? Instead, I just try to approach it like I would with poetry: to capture the feeling of what it is I’m trying to say.

“That’s different from when I first started writing, when I felt you had to tell a story and it had to be very clear. And the most important change, I guess, is that I have decided – rightly or wrongly – to tell the absolute truth about my own experience and my own viewpoints. If I stick to being as authentic as I can be, that has power in it and an ability to connect with other people in ways that a more studied approach wouldn’t.”

What do you think you learned from the other guys in the band?

“That’s another question that I’ve never even stopped to reflect upon. Patience, I think, more than anything, and the ability to listen more deeply to what is actually happening, musically. And a study of melody, probably. You know, I had been in a band for a long time before Garbage, so a lot of the really basic things you learn from other musicians in that regard, I got probably from me previous band – about how to write, how to structure, how to excite, how to use dynamics.”

Who were your influences?

“I’m 52 years old so the people who influenced me, initially, with my songwriting, would be who I listened to when I was young. I had a very varied musical upbringing. I sang classical choral in the choir until I was 15, I played in a school orchestra, I studied piano, violin and clarinet. So I had a very conservative musical upbringing and my mother was a singer, so she introduced me to a lot of great jazz singers, from Ella Fitzgerald to Billie Holiday to Nina Simone and Sarah Vaughan and, ad infinitum, Peggy Lee. So that was a huge influence on me, from a vocal standpoint.

“Then I fell in love with post-punk: Siouxsie & The Banshees, Clash, early Adam & The Ants, The Slits, and bands like this. And then I discovered, finally, people like Patti Smith, Debbie Harry and Blondie. So I’ve had so many. I feel like every artist that you fall in love with – whether it’s through a song or an album – has an influence on you, in some way or another. And they’re not necessarily direct influences, they just seep into your DNA.”

Shirley Manson in Songwriting Magazine: “A band is, unfortunately, a business, whether we like it or not.”

In what other ways do you become creatively inspired?

“I’ve always been very interested in theatre and I love movies, and I’ve only recently become more and more interested in the visual arts. I’ve been ignorant and never went to art school, so I’m very late to come to the table with regards going to art galleries and actually finding immense joy in that.”

You’ve appeared as a vocalist on a lot of tracks outside Garbage, but haven’t had an obvious career as a solo artist. Was that a conscious decision? Is that something you still might do?

“I would be a liar if I said I hadn’t pursued that idea at some point – I most certainly did – but the gods were with me in that it, actually, never came to fruition, for one reason or another. Because I don’t think I would’ve ever returned to Garbage had I gone and stepped out on my own. I’m very lucky that I have

a band that still functions as a creative unit and I enjoy the collaborative efforts of that.

“We’re now realising what a privilege it is to be a band with a 25-year discography, and the luxury of that – going out to play and pick between hundreds of songs is joyful. So the older I get, the more and more I feel determined to invest in my band, but I would do whatever it is that I need to do as a creative person. If the band split tomorrow then, yeah, sure, I’d make a solo record. But as it is, my band are still going and we’re reaping the benefits of that tenacity.”

What do you think has been the key to your longevity as a band?

“I’d say the most important thing is to split everything equally. A band is, unfortunately, a business, whether we like it or not. You get a fee for playing, so you’re immediately in business with your bandmates, and I think it’s important as a band to understand that everybody’s pulling the cart, and the weight of everything, equally. Therefore, everybody has to be fairly compensated for their benefits, otherwise there’s no reason for them to remain committed.

“And I think there has to be an appreciation for everybody’s talents. If you’re willing to adapt, and move with the unit, then you come to unexpected places and that’s exciting. You’d never get that if you’re a dictator within a band unit, and if you are a dictator then the band will explode.”

So is it a case of ‘leaving your egos at the door’ when you start the band and maintaining that balance?

“Well, I think people describe ‘ego’ in a very negative way. To me, the ego is absolutely vital to the survival of a human being – if you don’t have an ego, you’re just going to be a doormat. So I don’t believe ego is a negative thing. Everyone in my band has a huge ego – they may not think they do, but they do – and it’s as big as mine, but I’m a different kind of ego. I think if everyone is understanding of each other’s ego then you can move forward together, collaboratively, and it creates something really unique. That’s what I’m interested in and excited by and I think so too are my bandmates.”

Tell us more about The Jump with Mailchimp. Whose idea was it and how did it come about?

“I’ve absolutely no idea! It was one of the most extraordinary phone calls I’ve ever received in my life. I knew Hrishikesh Hirway from Mailchimp, who was the originator of the Song Exploder podcast and I was one of the first guests, years and years ago. At that time, he was literally just with a mobile recorder and microphone, and his podcast just exploded, and I believe he was the one who presented my name to Mailchimp as a possible contender for the host of The Jump.

“So I got the phone call and I was thrilled, but I was also a little trepidatious about doing it because I’m not a journalist and I don’t consider myself as a music boffin – I’m not a facts and figures nerd at all. But I love talking to musicians and I’m curious about people, so I said ‘yes’ even though I felt physically sick every time I interviewed someone!”

That’s surprising to hear, considering the huge audiences you’ve performed in front of. Is it because it was out of your comfort zone?

“It’s very intimidating and way out of my comfort zone! But also I know that I love to talk to people and I’m genuinely fascinated by other people’s experience. And it was such a fantastic opportunity, I knew I’d be an idiot if I turned it down. So I said ‘yes’ and I’m very grateful that I did because I got to have these amazing conversations with musicians I’ve nothing but great respect and so much love for.

You’ve done eight episodes for the podcast so far. Is this a one-off or do you plan to do more?

“I’ve already signed on for my second season, so I’m really excited.”

How did you go about selecting the interviewees? Were you personally involved in the process?

“Yeah, I sent them a sort of dream list of people I’d like to talk to, and they had a dream list, and we found that we both had many of the same names on the list. Of course, a lot of it was to do with availability and time, but I’m thrilled that so many great artists consented, I was really kind of amazed.”

Can you reel off a few of the names on your wishlist, who you haven’t interviewed yet?

“There are so many, I don’t even know where to start! But I will confess, I’ll give you one name, because it was the first one on my list when I was asked if I would do this: I said, ‘Please, go out and get me Siouxsie Sioux.’ But there are millions of artists that I’d love to speak to. I’d love to speak with Brent [Hinds] from Mastodon, for a start. And, I don’t know, someone like Kamasi Washington… There are so many, but I want Siouxsie Sioux, that’s my dream!”

Related Articles